|

July 12, 2001, page 1

The satellite imagery of Nikumaroro recently obtained especially for TIGHAR by Space Imaging of Thornton, Colorado (www.spaceimaging.com) has provided The Earhart Project with a search and search management tool of unprecedented value and utility. Blessed with minimal cloud cover over the island and virtually no sun-glint to obstruct our view into the water we now, for the first time, have the ability to look down on the atoll like one of the frigate birds who live there.

Of course, from the beginning of our investigation in 1988, we’ve used historical aerial photos of the island to research and document its features and search for any sign of Earhart, Noonan, and the Electra – and we’ve found some. It was forensic imaging analysis of 1941 photos by Photek, Inc. of Portland, Oregon in 1995 that led us, the next year, to the artifacts at what we call the “Seven Site.” Descriptions in British files describing the finding of a skeleton (Earhart’s?—see Gallagher’s Clues) on the island in 1940 now lead us to strongly suspect the Seven Site as the place where that discovery occurred. Forensic analysis of aerial photos taken in 1938 has revealed the presence at that site of features which appear to be worn footpaths at a time before the first settlers arrived on the island. We’ll be taking a hard look at the Seven Site when we return to Nikumaroro later this summer.

As valuable as these old photos have been in documenting the past and providing clues for the search, they are of limited use in planning and managing search operations in the present. The island’s vegetation and man-made features have changed over the years. What was once open forest is now dense underbrush. Orderly coconut plantations have become jungles. Houses and administrative buildings have come and gone like the people who built them, while the SS Norwich City has steadily deteriorated from stranded wreck to scattered wreckage.

What we’ve always needed is high-quality color imagery that shows us exactly what is on the ground and in the water today. The Royal New Zealand Air Force was kind enough to give us copies of photos taken during routine fisheries patrol flights, but they were casual snapshots. We looked into hiring an aerial photo mission but Nikumaroro’s remote location made such a venture prohibitively expensive. During Niku II in 1991 we tried a video camera-carrying kite, but stability in the strong trade winds was a problem (just watching the tape made everybody sick.) We brought along an ultralight aircraft on the 1997 Niku III expedition (no small undertaking, that) but the seas were so rough and the wind so strong that we were never able to fully assemble the airplane, much less launch it. In 1998, during our flying expedition to Kanton Island, we hoped to make a photo run over Nikumaroro in our chartered Gulfstream I but low rain clouds and fuel concerns made it too dangerous to try.

Satellite imagery was an option we explored on several occasions, but the only existing picture of the island from space was a conventional photograph taken through a window of the Shuttle, and ordering a special mission from one of the few commercial outlets was far too expensive – until we learned about Space Imaging. Through close coordination with the company’s management and a cooperative arrangement with the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) we were able to tailor an affordable mission that acquired data for TIGHAR’s use in The Earhart Project and NOAA’s use in its study of the world’s endangered coral reefs.

Recent analysis of the satellite imagery and historical photos of Nikumaroro has raised the possibility that the aircraft wreckage on the reef supposedly seen by Emily Sikuli (see The Carpenter’s Daughter) may still be right where she saw it.

In 1999 Emily told us of seeing debris on the reef at Nikumaroro in 1940 or ’41 which her father, the island carpenter, told her was the wreckage of an airplane. Her story was particularly interesting to us because the general location she described, the reef-flat off the western end of the atoll, was where a variety of other anecdotes and evidence had already led us to suspect that the Earhart airplane had been landed and subsequently destroyed by the surf.

Emily

was quite specific about what she saw and where she saw it. She spoke

of a red, rusty object which she estimated to be about 12 feet long with

a large round shape at one end. She said that it was out at the reef edge

“where the waves break” and that it was about 300 feet north of the wreck

of the S.S. Norwich City. The wreckage, she said was in very bad

condition and could only be seen at low tide.

Emily

was quite specific about what she saw and where she saw it. She spoke

of a red, rusty object which she estimated to be about 12 feet long with

a large round shape at one end. She said that it was out at the reef edge

“where the waves break” and that it was about 300 feet north of the wreck

of the S.S. Norwich City. The wreckage, she said was in very bad

condition and could only be seen at low tide.

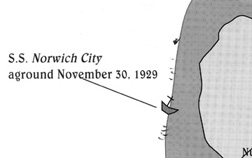

This is the map Emily marked for us during her interview. The darker, larger mark farthest north is her mark. The smaller marks were made to show her where the surf breaks.

Looking

for possible photographic corroboration, we examined a photo of that part

of the reef taken by British Colonial Officer Eric Bevington during a

visit to the island in October 1937. There, a few yards ahead of the bow

of the Norwich City, could be seen some kind of debris on the reef

which seemed to match Emily’s description. Another photo, this one taken

in 1939 by the New Zealand survey party, showed something on the reef

that might be the same feature.

Looking

for possible photographic corroboration, we examined a photo of that part

of the reef taken by British Colonial Officer Eric Bevington during a

visit to the island in October 1937. There, a few yards ahead of the bow

of the Norwich City, could be seen some kind of debris on the reef

which seemed to match Emily’s description. Another photo, this one taken

in 1939 by the New Zealand survey party, showed something on the reef

that might be the same feature.

Eric Bevington took this photograph in October 1937. Photo courtesy E. Bevington.

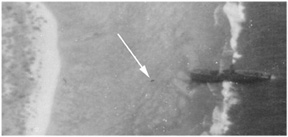

The

New Zealand survey party took this photograph in December, 1938. Photo

courtesy Wigram Air Force Museum, New Zealand.

The

New Zealand survey party took this photograph in December, 1938. Photo

courtesy Wigram Air Force Museum, New Zealand.

The 1938 aerial photo and the Kiwi detail photo. Photos courtesy Wigram Air Force Museum, New Zealand.

The question of whether the features in the Bevington and New Zealand photos could be Emily’s Object relied upon determining just where on the reef the feature was. Jeff Glickman at Photek spotted a chunk of something on the reef not far from the bow of the Norwich City in a 1938 aerial photo taken immediately prior to the New Zealand survey. Photos taken by the Kiwis on the ground during that survey show that chunk to be a slab of hull plating from the shipwreck.

The feature in the Bevington photo was in that same location. Clearly this was not corroboration of Emily’s story.