|

July 12, 2001, page 2

|

|

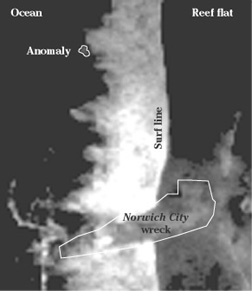

The panchromatic (black and white) satellite imagery that was acquired simultaneously with the multispectral (color) imagery is much tighter, with a single pixel representing one meter on each side, but again, each pixel is influenced by its neighbors. Although the panchromatic picture presents more detail, it does not penetrate the water nearly as well as the blue/green band of the multispectral image. Looking in the same spot as the maverick pixels in the color image, we see five pixels in the panchromatic image that appear to be distinct from the background and the surf. The implication is that there is something there that is roughly three meters (10 feet) long and variously one to two meters wide, but again, that can be deceiving. About all we can say is that the feature is present in both images and seems to be larger in the color image than in the black and white – which may suggest that we’re seeing more of it in the color image because of the better water penetration. |

|

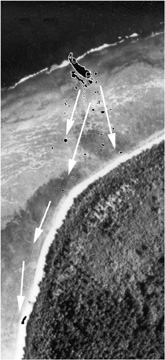

Norwich

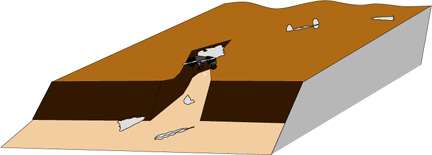

City debris field in 1985.

Norwich

City debris field in 1985.

A rust-colored something-or-other

on the reef so close to the Norwich City might logically be thought

to be shipwreck debris, except it’s in the wrong place. For most of the

year the weather at Nikumaroro comes out of the east and is relatively

benign, but from November until April (as we learned to our regret in

1997) immense westerly swells sometimes pound the island. The effect of

these rare but devastating events can be seen in the progressive deterioration

of the S.S. Norwich City. As the ship has broken up over the decades,

the debris field has scattered west and southwest – never north.

Norwich City debris field in 1999.

TIGHAR photos show that between 1989 and 1991 this tank moved approximately 100 meters.

Such a scenario does, in fact, fit the anecdotal, photographic, and artifactual evidence gathered by TIGHAR in the course of our thirteen year investigation.

Although

still of undetermined origin, the section of aluminum airplane skin (Artifact

2-2-V-1) found in 1991 exhibits damage that is consistent with its being

torn from an aircraft by powerful surf action. The piece has no finished

edges and was literally blown out of a larger section of aluminum sheet

from the inside out with such force that the heads popped off the rivets.

The interior surfaces exhibit none of the pitting that is normally left

by an explosion and one edge clearly failed from fatigue after being cycled

back and forth at least twice. The artifact was found on the island’s

southwestern shore in the debris washed up by a violent storm.

Although

still of undetermined origin, the section of aluminum airplane skin (Artifact

2-2-V-1) found in 1991 exhibits damage that is consistent with its being

torn from an aircraft by powerful surf action. The piece has no finished

edges and was literally blown out of a larger section of aluminum sheet

from the inside out with such force that the heads popped off the rivets.

The interior surfaces exhibit none of the pitting that is normally left

by an explosion and one edge clearly failed from fatigue after being cycled

back and forth at least twice. The artifact was found on the island’s

southwestern shore in the debris washed up by a violent storm.

In order for a section of skin to fail in this way, the airframe to which it is attached must be held relatively immobile.

The

evidence available at this time suggests the following sequence of events.

The

evidence available at this time suggests the following sequence of events.

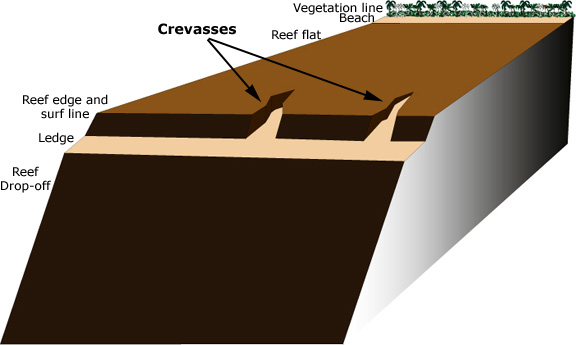

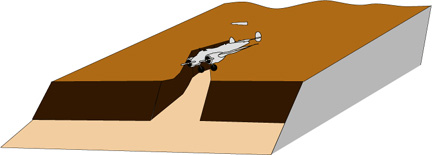

1. The aircraft is landed with minimal damage at low tide on the reef flat north of the Norwich City but irregularities in the reef surface prevent the airplane from being taxied to a safer location. Over the next few days the tide rises and falls but calm seas leave the aircraft relatively undisturbed permitting the sending of radio distress calls.

2.

On or about July 5th increasing swells and rising surf on the reef force

the crew to abandon the aircraft and seek shelter ashore. The waves wash

the buoyant Electra back and forth until it falls into a groove feature

near the reef edge and becomes jammed there.

2.

On or about July 5th increasing swells and rising surf on the reef force

the crew to abandon the aircraft and seek shelter ashore. The waves wash

the buoyant Electra back and forth until it falls into a groove feature

near the reef edge and becomes jammed there.

3.

Held immobile by the coral, the Lockheed is quickly ripped apart by the

crashing surf. Some parts are pulled out and over the steep reef slope while

others are scattered shoreward across the reef flat. The massive main beam,

with engines and landing gear attached at each end, remains wedged in the

reef groove.

3.

Held immobile by the coral, the Lockheed is quickly ripped apart by the

crashing surf. Some parts are pulled out and over the steep reef slope while

others are scattered shoreward across the reef flat. The massive main beam,

with engines and landing gear attached at each end, remains wedged in the

reef groove.If our speculation is correct, the information and illustrations in this newsletter provide a veritable treasure map to the location of the remains of Amelia Earhart’s lost aircraft. Are we nuts to make this information public? We don’t think so.

First of all we think that you, the supporters of TIGHAR – the people who are making this investigation possible – have a right to know the results of the research you are funding.

Second, it’s still just a hypothesis. Looks good to us but, heck, each time we’ve gone to Nikumaroro (five times so far) we’ve had a theory about where we should look for the airplane, and each time we’ve been wrong.

Third, even if someone with lots of money and no ethics were convinced that we finally had the answer, it would be extremely difficult to get there ahead of us.

Fourth, we’ve always said that the point of the project is the development and demonstration of sound historical investigative methodology. That purpose is not served by secrecy. Our failures are as important as our successes because they’re an inevitable part of the process.

And finally, if it turns out that we’re right, we’d rather that everyone know that we figured it out instead of just getting lucky.