Carrigaholt to Belle Isle

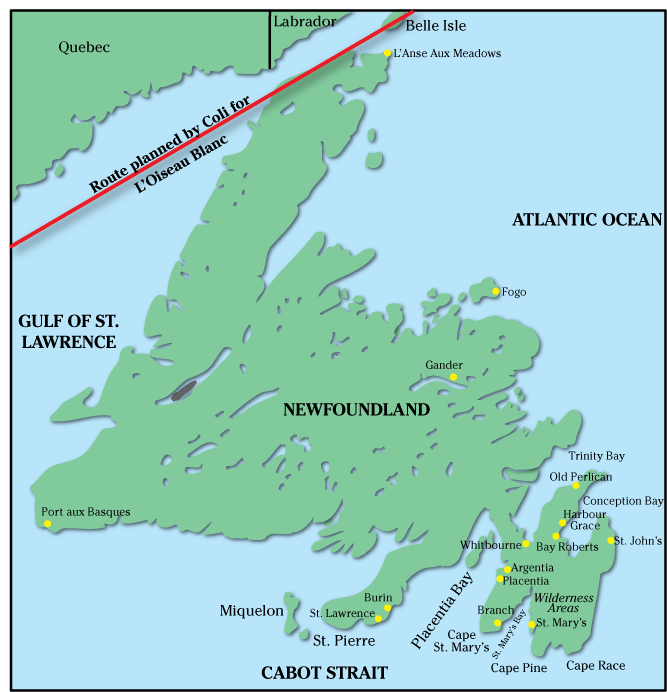

What weather did l’Oiseau Blanc encounter as it left the coast of Ireland? The meteorological conditions over the ocean will not be studied in detail, but primarily from the point of view of the wind. In fact, it is necessary to examine the reports from the other side of the Atlantic with as clear an idea as possible of what a reasonable time of overflight is, and if in fact this overflight took place.First, one simplification, which does not remove, however, all one’s interest in the analysis which follows: we have postulated that the route followed by Nungesser and Coli was established in such a manner as to be close to the arc of the great circle which joins the mouth of the Shannon, in Ireland, with Belle Isle in the north of Newfoundland. The calculations were made for only a few points along the course.

The map below indicates the estimated positions of l’Oiseau Blanc, in UT, in the course of the days of May 8 and 9, 1927. This map also indicates the approximate time of sunset on this course at the moment the aircraft passed it. This last figure was deduced from that which was furnished us by the bureau of longitudes, and which concerned the time of sunset at latitude 51°50′N.

The estimates which follow concerning the direction and force of the wind for the different portions of the plane’s course come from the analysis of the documents listed below:

- 1928 Meteorology Report

- Letter from The National Meteorological Library, op. cit., giving commentaries on the weather and accompanying the dossier comprising the meteorological statements from British stations on May 8 and 9, 1927, the isobaric maps from May 8 and 9, and two maps synopsizing May 8 and 9 at 1300 GMT, covering almost all of the northern hemisphere

- Study from the Weather Bureau in Washington (synopsized in l’Aéronautique Nº 105 of February 1928)

- Letter from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration of the U.S. Department of Commerce from February 3, 1981, forwarded by the Federal Aviation Administration in Washington on May 3, 1981, and sending the meteorological commentaries from the station in Boston (Massachusetts) for the month of May, 1927, and the US maps synopsizing the northern hemisphere for May 7, 8, 9, and 10, 1927, at 1300 GMT.

At the moment they left the Irish coast at 1000 UT, the aircraft was supposed to be at a power of 425 HP and at an indicated speed of about 173 km/h. It should have stayed at these settings for about 45 minutes. The wind over this portion of the course was estimated at SE 17 km/h, which would give a ground speed to the aircraft of 187 km/h. In 45 minutes the aircraft would travel 140 km. They would then change in principle to a power of 400 HP and stay there for an hour and a half. The indicated speed would then be 169 km/h. They had the same wind for this part of the course, but slight change of heading which gave a ground speed of 180 km/h. Based on this ground speed of 180 km/h, they should have attained 20° west at the end of 3 hours 40 minutes, or at 1340 UT.

The wind on which this portion of the anticipated flight plan was based was on average SE at about 8 km/h. The lateral deviation of the route in arriving at 20° W in relationship to the great circle may well be considered negligible, but the aircraft must have been ahead of the time table anticipated.

In the course of this part of the trip, the weather was probably not bad, and Coli could surely get sightings. These must have confirmed to the aviators the idea that they had a good weather forecast, and encouraged them to pursue their attempt if the functioning of the motor and the performance of the aircraft were satisfactory. At 20° W the total weight of the aircraft would be in the neighborhood of 3791 kg, gotten by deducting from the take off weight of 4864 kg the weight of the landing gear (123 kg) and the weight of the fuel consumed, about 950 kg. The reactions and the control of the machine were then familiar to the pilot, because some test flights were made, it appears, at this weight (we must not attached too much value to these numbers’ seeming precision; but rather view them in the spirit in which the calculations were established).

From 20°W, any knowledge we may have about the flight becomes more tenuous. Crossing of the 20° line would take place about 1340 UT. For the aviators, who had seen the sun at its zenith before 20°W, the star was fleeing in front of them. They would probably pass to the north of a small depression which, according to the meteorology report, would have brought only light rain on their course and would have had little effect on the aircraft. They were also probably to the northeast of a stronger low pressure area, which continued to give them favorable winds. The weather must not have been very bad.

The meteorology report estimates that the winds were favorable, clearly tailwinds, almost to 40°W. The letter from The National Meteorological Library, mentioned above, cites the Historical Weather Maps indicating that the summarizing maps from May 8 at 1300 GMT shows that at this time the wind would still be coming from the ESE. The study of the weather maps for transatlantic flights, made in 1927 by the Weather Bureau in Washington and summarized in l’Aéronautique Nº 105 of February, 1928, contains this remark: “Whereas before a light wind of about 20 km/h aided the aircraft on its flight, from about 31° longitude the wind freshened gradually to the southeast…”

We know that the lateral deviation of the aircraft from its original stated course was negligible. From 20°W to 40°W, it would travel nearly 720 NM (or 1333 km) in the vicinity of the arc of the great circle. We can fix approximations of the successive points for changing the power settings and the heading after crossing 20°W, and we can calculate the speeds and the distances for the trip.

The crossing of 40°W would have occurred at about 2100UT on May 8. The sun would still not be very low in the sky (at this same longitude, but at 51°50′N, the sun set at 2213 UT), and probably the flight would still be proceeding normally. Coli could regularly verify the route, in spite of the weather being without doubt somewhat cloudy. The crew had been flying about 17 hours.

After 40°W, the weather situation encountered by the crew is difficult to know. The meteorology report says that the evolution of the depression situated to the east of Newfoundland was the one indicated before the departure, while the study cited above by the Weather Bureau of Washington thought that this depression had moved very much less to the east than the crew had anticipated. The latter would have as a consequence for the aircraft approaching Newfoundland first a ground speed different from that planned, and at the same time a drift factor which was probably important, with snow falling and atmospheric pressure much lower than that anticipated. Against these difficulties, it is appropriate to assume that the crew was making the necessary decisions to assure their safety, and that they conducted their navigation bearing in mind the exterior forces.

If the weather situation was that forecast by the ONM, the crew probably pursued their journey closely following the course planned.

The work of reconstructing that course, as done above, is easy. If the wind continued favorable, the aircraft would be over Belle Isle 6 hours 55 minutes after leaving 40°W, or by rounding at about 0400 UT May 9. The meteorological report, page 127, reports the anticipated flight over Belle Isle to be 0500 UT May 9, given a departure from Bourget at 0400 UT May 8. For the trip between 40°W and Belle Isle night had fallen when l’Oiseau Blanc was at about 45°W. The most difficult part of the over water trip was therefore to be done at night. If the sky was clear, at least now and then, astronomical sightings would permit Coli to plot his position.

If the weather conditions were those indicated by the Bureau in Washington, the flight happened in very different conditions. Some decisions must have been made by the crew, who encountered weather which was certainly difficult – possibly very bad – which would render astronomical navigation impossible, and rendering the flight susceptible to large deviations in following the course planned, deviations of major drift with critical delays in the planned time schedule. It is useful to remember here that the interview with the engineer Barbarou, reproduced in Le Journal of May 13, 1927, contained this sentence: “It is essential to be aware that it was absolutely settled that Nungesser and Coli would not wrestle with fog, nor with a storm; and that they would change their heading, in case of anything unexpected during the trip, to pass above 57° north latitude, that is to say towards northern Canada, Labrador, and perhaps even Greenland.”

It is important to note that night had fallen for the crew towards 2300 UT, about 45°W. Sunrise on May 9, 1927, took place on Belle Isle at about 0800 UT.

An understanding of the course followed and the corresponding schedule, in these conditions, becomes very problematical. If the aircraft effected a passage over Newfoundland, the course which was plotted and which led to a large detour to the north, perhaps above 55°N, to avoid the disturbance, to lessen the grave risk posed by the night, and to possibly permit navigation, led to a lengthening of more than 220 NM (407 km). If one postulates that the wind encountered was then blowing from the SE during the first part of the course deviation, and NE during the second part (to simplify), and the same velocity is used as in the first hypothesis, one can estimate that the extra time necessary for this course deviation is on the order of 3 hours. This brings us to a point over Belle Isle at about 0700 UT on May 9. If l’Oiseau Blanc was still in flight at this moment, one can imagine, given the part of the course over the Atlantic effected at night, with what the crew had for weather conditions, and during which they had been en route for more than twenty hours, the experience would be extraordinarily painful.

Belle Isle to Harbour Grace

We will examine a little further on some testimony describing a flight over southeast Newfoundland. In order to simplify, we have done the calculations as if l’Oiseau Blanc, if it was indeed the aircraft, had gone to southeast Newfoundland, passing by Belle Isle, keeping in mind the depression situated to the east of Newfoundland.The distance between Belle Isle and Harbour Grace (23 NM to the WNW of Saint John’s in Newfoundland – see the map, right), is about 265 NM or 490 km. In direct flight l’Oiseau Blanc could make this flight in two and a half hours, if the wind was NW at 45 km/h as reported in the meteorological observations. This leads to an overflight of Harbour Grace at 0630 UT or 0930 UT on May 9, according to whether the course followed to Belle Isle was the arc of the Great Circle (orthodromy) or the course deviation to the north.

We admit that the total trip from Ireland to Newfoundland reconstructed above, and presenting two variations for the last part, is calculated in such a way as to present minimum duration for the flight; and that actual duration of as much as 20% more would not be astonishing. This is to say that the overflight of Harbour Grace in Newfoundland could take place, rounded off, at between 0630 UT and 1400 UT on May 9. At this point, however, it is essential to insist that the hypotheses laid out do not by any means signify that we think that l’Oiseau Blanc could not have been at Harbour Grace on either side of this bracket; but that the probability is much less.

Sunrise at St. John’s occurred at about 0810 UT as the data furnished us by the Bureau of Longitudes allow us to determine. An excerpt from the Newfoundland Yearbook and Almanac for the year 1927 obligingly furnished by the archivist from the province of Newfoundland, shows that, in local time, the sun rose at St. John’s on May 9 at 0441. This permits the determination that the official time in Newfoundland was UT minus three and a half hours, and not four hours as one might think given the corresponding time zone.

What was the weather like over Newfoundland, St. Pierre, and Miquelon on the morning of May 9, 1927?

The Times of May 10 reported that on the previous afternoon, the fog stretched from New York to Nantucket. However, between Nantucket and Newfoundland, the visibility was clear with cloudy skies and a brisk wind from the north east. To the east of Newfoundland there was a storm, accompanied by fog, rain, snow, strong winds, and very low barometric readings. On the other hand, Vern Hutchinson, in an article published in the Washington Post on August 13, 1972, says that the entire North Atlantic coast from Newfoundland to New York, was blanketed in fog. The weather reports sent from the North American continent to Paris were as follows for May 9, 1927 (quoted at 1300 UT), concerning Newfoundland (the stations cited are noted on the map, above; data furnished by the Department of Meteorology):

Station Pressure Temp. Wind Sky Burin Port aux Basques Fogo Belle Isle From the statements which we will see later on, it appears that the fog remained in spite of a strong wind, but was more or less dense according to region. It was freezing at ground level only in the northern part of Newfoundland. None of the testimony which we will examine reports rain or snow falling.

The Testimony Collected

The reports are quite numerous. Very few mention visual contact with the plane, but concern simply the hearing of the noise of an aircraft. They were dismissed as a body by the French dailies, but with no details furnished. (Let us recall the possibility of l’Oiseau Blanc having been shot down in flight by machine guns wielded by rum-runners in boats off North America, as mentioned in the forward to M. Marcel Jullian’s book Nungesser, l’As des As.) The greater part of the testimony we will discus below have been, with the usual variations, reproduced in one form or another in the Montréal press. We also find them in English and French newspapers.In the daily La Presse of May 16, 1927, the text below was published:

New York, 15 May. Three people claim to have seen l’Oiseau Blanc. One is Miss Alice Kelly, who declares that she saw an airplane whose colors she could not distinguish. The two others are two members of the Canadian Parliament, Mr. Eben Penddle and his son, who reside at Bearcove. They distinctly saw an airplane between 9 and 10 o’clock, Monday morning, making for the northwest. On learning of the disappearance of the aviators they went to Harbour Grace.The same information was also mentioned in Le Matin and in Paris Sport of May 15.The principal interest of this text is in the fact that it gave the names of the two witnesses who had distinctly seen the aircraft, and who were members of “Canadian Parliament;” and as a consequence it might be possible to obtain from the Canadian government not a confirmation or denial of the testimony – except by extraordinary luck – but at least a confirmation or denial of the existence at that date of two Members named Penddle and residing at Bearcove. If this could be affirmed, the character which attaches itself to such an office would be an important guarantee of the testimony. A letter was sent to the Canadian Embassy in Paris; then, on the suggestion of the press counsellor there, directly to Newfoundland.

The author of this report, while sending this letter, was aware of course that this same paper La Presse reported in its May 17 issue that “the following telegram coming from the radio agency was published yesterday: all the reports concerning the flight over Newfoundland are erroneous.”

The provincial archivist of Newfoundland responded on December 29, 1981, and sent photocopies of interesting pages from the paper The Evening Telegram of St. John’s from May 12 and May 16, 1927; and a detailed map of the area of St. John’s and Harbour Grace (and mentioning the location of Bearcove, which at that time was merely an extension of Harbour Grace consisting of parcels of land and a few houses). He reported in his letter that the information on the subject of the two parliamentarians was inexact, but that there had been families named “Peddle” in the area for a long time, and that it had to be them.Page six of The Evening Telegram of May 12, 1927, contains the testimony of inhabitants who only heard the plane. These declarations were made on the one hand in an unsigned article, and on the other in a communiqué signed by Judge John Casey (Stipendiary Magistrate), who received the depositions. Below we will find the summary of these reports, of which one, that of Patrick O’Brien, is not mentioned in the communiqué from Judge Casey. (All of the places cited on the following pages have been marked, in that they concern Newfoundland, on the map above.)

Mr. O’Brien, working in the fields on a hillside near Harbour Grace, heard the noise of airplane exhaust at 9:30, from the north and at a distance estimated at about 10 miles. He knew nothing about l’Oiseau Blanc’s flight. The wind was from the north. Judge Casey, questioned by a representative from the Telegram, said he was convinced that the statement made by Patrick O’Brien was correct.

Mr. John Stapleton and Mr. Moriarty, who were in the middle of the town at the same time, heard the sound of an aircraft coming from the north to northeast at a distance estimated at 5 miles. Neither had heard of the flight of l’Oiseau Blanc. Mr. Stapleton believed he had heard a seal hunting plane. The fog interfered with visibility.

Mr. O’Brien and Mr. Stapleton affirm that the noise was the same as that from the Handley Page which flew over Harbour Grace in 1919.

Mrs. Hinton, Harbour Grace, wife of the director of the Imperial Cable Company, heard the same noise coming from the north between 9 and 11 o’clock. She had lived in England near a training field for seaplanes and knew the sound well.

Mrs. R.S. Munn, Harbour Grace, heard the sound of an airplane coming from the northwest at about 9:30 to 10 o’clock.

Page five of The Evening Telegram of May 16, 1927, contains the accounts of two inhabitants who saw the aircraft (in fact, this article contains the essence of the depositions of the two witnesses to Judge Casey). They are quoted below (translation [into French] STNA):[1]

Deposition of James Peddle.Peddle explained when questioned that he did not know of a plane flight until Friday the fourteenth, when he saw in The Evening Telegram an account of the missing airmen, and later it occurred to him that he should report the matter.James Peddle, aged 18, labourer, was working on the Cottage Road Monday morning not far from [the] aerodrome, used some years ago by the Handley Page which was stationed there, when he heard sounds as of a plane out in a north east direction towards the island of Bacalieu [15 km to the NE of Old Perlican – CPM]. “About two minutes afterwards,” he said, “I saw what I am positive was an aeroplane of a white colour coming over the land from the north east bearing about South West for a few minutes. Then it passed quickly to the South for a few seconds, and then changed its course to north west half north. It continued on that course which to the best of myjudgment would put her on a line to the North of Harbour Grace. It continued on that course till I lost sight of her.”

Peddle explained that he was well-acquainted with the appearance of a plane and the sound it made from the fact of the Handley Page being stationed in Harbour Grace. He also often saw the plane used by Major Cotton in the sealing flights.

Annie Kelly.We should make clear that The Evening Telegram of May 16, 1927, also published a sort of editorial about the attempt of l’Oiseau Blanc, from which we extract the following lines which begin the article (translation [into French] STNA):Annie Kelly, a married woman residing in Harbour Grace, South Shore, swore that between 9:00 and 10:00 in the morning of Monday, May 9th, she was working near her house when she heard a buzzing sound that seemed to be overhead. The noise passed over her house, it seemed, and searching to find out what caused it, she saw over her and going south what she took at first to be two big gulls with their wings touching. They were two large white wings on a line with each other, but she knew the object could not be a bird from the strange sound it made. She did not report the matter earlier, because she did not know anything about the missing aeroplane until she saw it in the Harbour Grace Standard on Friday night, and then she thought she should report the matter.

This same article says that Judge Parsons of Harbour Breton states that two men from that area heard strange sounds on Monday morning, similar to an airplane. If the course given by James Peddle, as seen in the article, is considered possible, it is not unreasonable that the aviators, blocked by the Middle Ridge Mountains, followed them in a southerly direction.Did French Airmen Meet Their Fate in or Near Nfld.?The information sent to the Minister of Justice by Judge Casey of Harbour Grace that two residents of that town had made sworn statements before him that they had seen an aeroplane pass over the town on the morning of Monday, May 9th, between the hours of nine and ten o’clock, appears conclusively to confirm the previous statements made by five other residents that they had heard a machine in flight at the same time. The explanation of the witnesses as to why they had not made the report earlier seems reasonable enough. They were unaware of the fact that the flight had been undertaken and no news reached them until Friday last that an aeroplane was missing.

We will also note that some daily newspapers make reference to the testimony of Miss Julia Day, from Old Perlican, 20 NM from Harbour Grace, who heard the noise of an airplane in the morning; and to the testimony of Mr. Fletcher Beck of Sound Island, Placentia Bay, who heard the noise of a plane Monday around 12 o’clock.

The times mentioned above in the different statements are all compatible with the reconstruction of the flight with the course deviation – 9:30 legal time in Newfoundland corresponds to 1300 UT.

The Governor in office at Saint-Pierre at Miquelon, who had sent the steamship Dangeac to explore the Newfoundland area when he received the news, sent word that the noise of a plane’s motor had been heard by an inhabitant of Swift Current, hunting 13 miles west of that area, Monday May 9 about six in the evening (at this time l’Oiseau Blanc would have been in flight for more than 41 hours).

If the major stories centered in Harbour Grace that we have mentioned are true, Nungesser and Coli, after recognizing the area they were flying over, would know for certain that they could not reach New York, because their remaining fuel range was only seven hours 15 minutes. This certainty and the immense blanket of fog which was spreading beneath their wings would have reasonably led them to a daytime sea landing in Quebec with its innumerable waterways and lakes – a possibility which Nungesser and Coli did not exclude before departure. Other possibilities are Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, or Maine.

As we have already said, all of the witness reports were subsequently declared or considered erroneous. The May 17 issue of The Times published the paragraph whose translation follows [taken from English original]:Hope is fading fast that Captain Nungesser and Captain Coli will be found in Newfoundland, Labrador, or Nova Scotia. Investigators at Harbour Grace are now inclined to believe that the persons who said they saw or heard an aeroplane there on May 9 were self-deluded.L’Humanité of May 17 also says that an inquest held in Newfoundland contradicts the testimony. But we have not found at any time in the French newspapers any report of this sort: “Mr. X has retracted his former statement and has recognized that he was mistaken.” Indeed, the governor of Saint Pierre et Miquelon sent a telegram on May 23 1927 to the Consul General of France in Montréal to confirm the testimony from Harbour Grace and Swift Current (however, this last is not very credible), and to indicate to him that the investigation yielded no results. All of this is confirmed again in Nº 41 of Foyer Paroissial, dated June 1—15, 1927, a local gazette from Saint-Pierre. This same Foyer Paroissial, in Nº 42 (June 15—30, 1927) reports that the Dangeac undertook on May 17 a second cruise along the coast of Newfoundland, with no success, and returned to Saint-Pierre on May 22. All of these telegrams and the copies of the press excerpts (the excerpts from Foyer Paroissial were reproduced by M. Lehuenen, who authenticated the text with his signature but did not say if the articles themselves were signed) were sent by the Prefect of Saint-Pierre et Miquelon on March 6, 1981.

To complete the series of witness reports concerning Newfoundland, we note without commentary the two below. La Presse of May 10, 1927 reports:

Saint John, Newfoundland, May 9. A torpedo boat signaled with a wireless that it saw, at 10 o’clock, a white airplane corresponding to the description of Nungesser and Coli’s passing south of Newfoundland. According to this news, the aviators would be two and a half hours later than the schedule expected.L’Humanité of May 10 gives the same information but speaks of a “destroyer.“ Le Devoir (of Montréal) of May 9 indicates that one signalled the passage of l’Oiseau Blanc off Cape Race at 10 o’clock “this afternoon.”

Lloyd’s Weekly Casualty Reports for June 3, 1927, sent by the French Embassy in Dublin, gives a report which can be translated as follows:

An airplane spotted off of Newfoundland. St John’s (NF), 26 May – The Danish schooner Albert which has just arrived in Belleoram, said that he had seen a plane on May, 80 miles off of Cape Pine. – Reuter. (Cape Pine is southeast of Newfoundland; Belleoram is inside of Fortune Bay. CPM.)Following our request for information, the Prefect of Saint-Pierre et Miquelon responded, as has already been noted, with his dispatch of March 6, 1982; and this dispatch contained in particular a written statement dated February 27, 1981, from Mr. J. Leheunen, former mayor of Saint-Pierre, reporting the remarks of a Saint-Pierre fisherman, Pierre-Marie Lechevalier, who was flown over while he was fishing south of Saint-Pierre by a plane that he did not see, but which could only have been l’Oiseau Blanc. The time of the overflight was not indicated.

The head of this department’s civil aviation service went more deeply into this affair and had a detailed report sent which was dated 22 December 1981, and from which the text below is an excerpt (the Head of the service is speaking):

At the end of November, 1981, I was looking after the sea plane “Jeanne d’Arc” and remembering l’Oiseau Blanc; M. Lehuenen told me the story confided to him by his neighbour, M. Clément Vallée, formerly a caulker in the port of Saint-Pierre.Then the report examines more closely the personality of Mr. Lechevallier, “a withdrawn, taciturn and solitary man;” and the genesis of this later testimony, which was confided for the first time to Mr. Vallée by Mr. Lechevallier on September 3, 1930, the day after the arrival of Costes and Bellonte in New York (Mr. Vallée was at that time 19 years old). This story was related for a second time by Mr. Lechevallier to Mr. Vallée “using the same words, the same details, and the same conviction” in 1945.On December 1, at M. Lehunene’s, M. Vallée told me himself the story that was told to him, in very much these terms, by Pierre-Marie Lechevallier, sea fisherman, now deceased.

On the morning of May 9, 1927, in a thick fog and white calm, I was finding the fish in an area about a mile and a half south of the black cape, when I heard a noise like the motor of an airplane … The noise increasing, I was quite sure it was an airplane … Suddenly toward the open sea, I heard a great crash like something very heavy fell into the sea … then there was total silence. At the same moment, my Newfoundland dog who was sleeping on the motor’s casing stood on his hind legs and started to howl; I had a lot of trouble making him be quiet … I went back to the port in the afternoon. It was one or two days later that I heard about the disappearance of the aviators Nungesser and Coli.

Mr. Lechevallier heard noise from a plane’s motor, then the sound of a crash into the water, but saw nothing because of the fog. His statement seems to allow the thought that the motor of the aircraft was functioning until the moment of the crash, and that the crash might well have been, in fact, an accidental impact with the surface of the water.

It is astonishing that Mr. Lechevallier stayed put and pursued his fishing, only returning to port in the afternoon. One may understand why he did not attempt to go alone in his rowboat in the direction of the impact point, which may have been distant; but one cannot comprehend why he did not return immediately to Saint Pierre to put out the alert. The explanation furnished on this point by the head of the Civil Aviation Service (that the fisherman knew that intervening would not be of any use) is not entirely convincing. It is equally surprising that Mr. Lechevallier waited three years before talking about what he had heard, when he certainly knew about, as did everyone in Saint Pierre, the searches of which l’Oiseau Blanc was the object in the days following May 9, 1927, and did not need to fear being reproached for his lack of initiative and his silence.

The body of evidence related above is very probably incomplete. A meticulous reading of the Canadian and American press of the time would certainly produce some interesting complementary material. But at this stage of the case, we must say that this evidence is not sufficient to remove the doubt which exists about the overflight of Newfoundland by l’Oiseau Blanc.

- The quotations here and following were obtained in the original English from the newspapers concerned and are printed here as they were seen at that time.

| Translator’s Note | Introduction | Chapter 1 | Chapter 2 | Chapter 3 |

| Chapter 4 | Chapter 5 | Chapter 6 | Supplement | Acknowledgements |