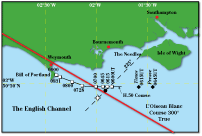

L’Oiseau Blanc then started out over the Channel, at a low altitude, on a northwesterly heading. Two opinions presented themselves from then on. Some support the idea that l’Oiseau Blanc cleared the Channel, Great Britain, and Ireland, suggesting that it either reached the continent of North America, or that it disappeared en route into the Atlantic. Others claim that l’Oiseau Blanc crashed into the Channel; and a few even that it went down not far from Etretat. The two accounts of the course to Etretat summarized previously tend to lead respectively to each of these conclusions. To facilitate understanding of the section below, the reader is invited to refer to the maps [at right] on which are shown the names of the places to which reference is made.

The Weather Situation Over the English Channel

Le Petit Parisien of May 9 published Carniaux’ report as stated above. One may note in particular that l’Oiseau Blanc, after having zigzagged, had the sea in sight at Bolbec (Bolbec is 25km in a straight line from Etretat). It seems that the visibility at the coast was not bad. And Carniaux adds “while we turned back in the direction of Paris, the aircraft was lost to view, far away between the water and the sky.”

L’Humanité of May 9 states that the visibility over the Channel was poor; and that at 6:45 a.m. the escort planes turned back and Nungesser and Coli started towards the English coast. La Presse of May 11, cited above, reports the statement of the pilot, a friend of Nungesser, who said of the difficulties with the weather over the Channel, “described wind and fog” which could have forced a sea landing. We should note in passing that this is a question of bad weather “described” and not “confirmed” by the pilot himself. The same daily paper, the same day, describes also the self-titled “Hypotheses” in which un-named spokesmen of the Navy and Air Force thought possibly a landing in the Channel was indicated because the airplane had not been seen in Great Britain or Ireland. Le Petit Parisien of May 12 reports in the clearest fashion that Léon Nungesser thought that his brother Charles was drifting off Etretat. It was at the insistence of Léon Nungesser particularly that searches were made in the Channel. These searches will be spoken of later.

Let us abandon the newspapers for the moment in order to examine other recitals.

In the book Toute l’Aviation [All Aviation] by Edmond Blanc (Société Parisienne Edition, 1930), we read that Captain Venson, who escorted the plane to Etretat, watched [as the aircraft], “flying very normally at 300 meters, plunged itself into the opaque milky greyness.”

In the book Ils ont survolé l’Atlantique [They Flew the Atlantic] by Robert de la Croix (Fayard, 1957), the author points out that “some feared that the heavy machine would not clear the Channel where very bad weather forced the retreat of the flying boats charged with the convoy.” And this same book cites also Captain Venson: “It (l’Oiseau Blanc) faded into the opaque milky greyness which contrasted against the color of the night which had lately come to a close.” In the book Nungesser, l’As des As, by Marcel Jullian (Presses Pocket edition, 1971), we read that Nungesser and Coli had “arrived at the Channel in a thick fog. This point was confirmed by the airplanes and seaplanes which had patrolled down close to the waves in low visibility.” The quote from Captain Venson shows also that he turned around in obedience to the orders he had received, and that he was convinced that l’Oiseau Blanc had fallen into the sea “less than 30 miles from the coast.” Unfortunately, the written report almost certainly made by Captain Venson on his return was not found.

Le Havre-Eclair of May 9, 1927, published an article datelined Cherbourg, May 8, 10 a.m., saying that just after that time the maritime headquarters, without news of l’Oiseau Blanc, sent out aircraft to the coast at Calvados and the Bay of Seine, while other machines explored the coast west of Cherbourg: “There is a lot of mist over the Channel and it isn’t impossible that Nungesser’s aircraft passed unseen because of it.” This mist did not appear to hinder the search. The Times of May 11 reports that the pilots of the seaplanes sent from Cherbourg to escort the plane over the Channel saw nothing, and found that the fog was thick enough to cause some difficulty with the simplest aerial maneuvers.

Reading the preceding pages gives the strong impression that on the morning of May 8 the visibility was bad to terrible over the Channel when l’Oiseau Blanc started out. A crash into the sea could of course have come from an engine failure, but it is appropriate to examine in detail the meteorological conditions which existed to determine if flight was possible without recourse to blind flight instruments; and if the searches and observance carried out had the chance to give a positive result in the case of a crash.

The Meteorological Bureau provided photocopies of the meteorological observations made by the the agents in service at the following stations for the month of May, 1927: Abbeville, Le Havre, Cherbourg-Chantereyne, Cap de la Hague, Iles Chausey. The observations for Le Bourget for the day of May 8 were also provided. An examination of the morning of May 8, 1927, gives Table 1 [below] at 0700 hours GMT, or 8 a.m., one and a quarter hours after the passage of l’Oiseau Blanc over Etretat.

Table 1

Pressure

CoverAbbeville Le Havre Cherbourg La Hague

(20-28 km/h) to seawardChausey

Of course, these measurements were carried out one and a quarter hours after the plane’s passage, but still do not seem alarming. The readings on the reverse of the page from which this information was taken, where precipitation is noted, gives for the day: nothing at Abbeville; at Havre a few drops of rain at 7:05 and at 14:30, and some rain and thunder at 14:45; and during the night, nothing at Cherbourg, nothing at Cap de la Hague, and some dew and some fog at Iles Chausey. These reports do not give the height or the nature of the clouds which caused the partial obscuration noted.

British weather services were also asked for the situation on the other side of the Channel on the same day and on the same morning. The National Meteorological Library responded on February 25, 1981. With their letter came the Daily Weather Reports from the Meteorological Bureau in London, which gave the reports in Table 2, below, for 0700 GMT on May 8 (see the maps of the Channel, above, and the route over England and Irelan, above right).

Table 2 Southampton

(12-19 km/h)Portland Bill

(20-28 km/h)

2500 ftPlymouth

(20-28 km/h)

5700 ftThe notes accompanying the documents and maps supplied will be used later. They are not directly applicable to the crossing of the Channel because the route discussed is that initially anticipated and published (Route Nº 1, above), and not the route more probably taken by the aircraft (Route Nº 4).

The ceiling varied from 760m at Portland (where l’Oiseau Blanc probably passed if it cleared the Channel) with a visibility of 10 km, to 1750m at Plymouth, with a visibility of 20 km. We will see later, in the discussion of the overflight of a British submarine near the coast of England, that “the visibility was no more than two or three miles.” (This report figured only in reports published by the French press, and was not reported in The Times.)

A photocopy of the registered telegrams to the Maritime Headquarters at Cherbourg (more detail on this point below) was sent by the conservator of archives of the First Maritime Region, after which the Historical Service involved itself following a request for information. The conservator of the archives watched carefully to be sure the research was properly done. He reported that “the lack of records, particularly about war ships, … is under the circumstances grievously felt.” The document reads:

May 7, 1927 – 14:45In Le Journal of May 9, 1927, G.D. Raffalovitch notes that Carniaux had seen Nungesser and Coli “take a clearly more northerly course, probably necessitated by the fog which settled close to the waves, which allowed them to stay on a line with the Southhampton steamers.”Forecast: Sky partly cloudy, foggy; winds moderate from the east, changing to south. Good weather continues.

Finally, the article appearing in Le Matin on May 9, 1927, for which the special reporter was surely aboard one of the accompanying aircraft, reported, “over the sea, the fog was tolerably thick; at the altitude of 800 meters, the visibility distance hardly exceeded 8 to 10 kilometers. Under us [on the order of 500 meters–CPM], l’Oiseau Blanc seemed an albatross skimming over the crests of the waves with its wings.”

The minimum temperature taken at Bourget for the day of May 8 was 15°C at 5:15 a.m., and the temperature taken at Havre at 7 a.m. was 16°C for that same day; this excludes the possibility of frost. No particular turbulence, which would have rendered control of the aircraft much more ticklish, was reported in any of the reading.

It appears that, contrary to popular opinion, the visibility and the weather encountered by Nungesser and Coli in the course of their crossing of the Channel did not present any grave danger. The line of the horizon over the sea was not clearly visible at their altitude, but the sky, partly cloud covered with occasional drizzle, linked with decent horizontal visibility, should have provided sufficient contrast. The crew would have made allowance for the mass lifted by the aircraft, and not left it to be piloted by the flight controller. If the truth be known, the aircraft and seaplanes elsewhere charged with the lookout and search probably did not do a very good job of the search; and it was only pursued for about 12 hours, on the same day of the departure. No accidents happened in the course of these flights.

Nevertheless, it is probable that the fog layer on the surface of the water would not facilitate the eventual location of wreckage or its identification.

An Overview of the Departure and the Searches

Now let us look at the arrangements made by the French authorities in the matter of the look-outs and the searches of the Channel (see the maps above – the Cape of Antifer is situated 4 km southwest of Etretat).The registry of telegrams at the Maritime Headquarters of Cherbourg, cited above, has these entries:

4 May 1927, 1945 hours To: Navy HQ Havre & Signals Antifer to La Hague Text: Departure Nungesser plane planned immediately, active aerial look out to be executed at the time of their passage for immediate information Cherbourg STOP Signals Antifer and Ouistreham both will inform the arrival Navy HQ Havre who transmit immediately intelligence to Navy HQ Paris Central Aero Service. 5 May 1927, 1115 hours To: Navy HQ Havre, Signals Between Antifer and La Hague Text: My 1264 will come before departure of Nungesser aircraft STOP For similar exercise watch with particular attention each morning at daybreak. 1715 hours To: Fleet Text: Watch for Nungesser aircraft will be carried out on Barfleur Star Point route beginning 6 May by Eveillé [Guardian] which should get under way from Cherbourg at the reception signal broadcast on 600m ends from Le Havre STOP Nungesser departure will happen between 0400 & 0600 hours give the Eveillé necessary orders STOP Information heading your signal that air look out will be done on the route Honfleur Barfleur Plymouth by machines from the seaplane base at Cherbourg STOP Report On May 5, a series of further messages about this look out on the same route was also transmitted. The Centaure was alerted to relay to the Eveillé. On May 6, we find similar messages.

The same summary of registered telegrams shows points (see map) for the disposition of look-outs:

May 1927, 1930 hours To: Director of Port Authority Text: Put Centaure under way in one hour for Sunday 8 May 0400. 1940 hours To: Signals Antifer to Le Hague and Navy HQ Le Havre for information. Text: My 1268 STOP Double watch tomorrow 8 May 0500 8 May 1927, 0545 hours To: Signals Antifer to Le Hague and Navy HQ Le Havre for information. Text: Nungesser’s aircraft left Le Bourget at 0520. A series of telegrams giving the next set of instructions or asking for information (including to Land’s End) shows the orientation of the search towards the west side of the Channel:

8 May 1927, 0935 hours To: Navy HQ Paris, Central Air Service Text: Advice received Nungesser airplane left Bourget 0520. Put immediately in play the disposition of aerial look outs and signal watches and Eveillé on Star Point squadron IR 2 Barfleur, Bay of Seine then towards Star Point STOP No news STOP Only order received to pass to Antifer four unidentified aircraft which arrived from east then returned. Communicated information to Levasseur Company by telephone STOP Requesting all information useful concerning course direction or stopping watch. Only at 1645 did information from the Levasseur Company show that the watch and the searches were not done in the correct area. The weather was becoming more and more foggy. The Eveillé group and the “torpedo submarine 315” group stopped their searches, but the Centaure was put back on “90 minute deployment.” The watch and searches did not locate the aircraft in or over the Channel.

8 May 1927, 1156 hours To: Navy HQ Paris, Aviation Text: Following my 1323. Continuing nothing new Nungesser in spite of searches done and information requested STOP In conformance with your telephoned instructions ceasing aerial searches until new clues and keeping Eveillé at sea until ordered otherwise. For May 9, the registry of telegrams doesn’t contain anything concerning Nungesser and Coli. We must conclude that, perhaps somewhat prematurely, no search or watch, sea or air, was done on this day. This is not surprising because information about the flight over Ireland was beginning to spread. Le Populaire of May 9 reprinted the originally planned course: Paris, Barfleur, Star Point … etc.; however, Le Matin of May 9 gives the course which was very probably followed over England and Ireland. What happened following this, when all the evidence showed the aircraft had disappeared?

A return to the telegrams of Cherbourg gives us on May 10, at 0740 and 0947 orders to:

for lighting the boilers in order for the ships to get under way as soon as possible to begin the search for Nungesser and Coli’s aircraft. Between 0950 and 1010 the orders to get underway immediately were transmitted to Centaure, torpedo sub 315, and Ailette in order to cover the following:

- Fleet for Eveillé [&] torpedo sub 315

- Port Authority for Centaure

- Ailette [Little Wing]

- Centaure, 1° line leaving Cherbourg for 10 miles on the 130 from Owers lightship

- Ailette, up to 20 miles on the 345 from Antifer

A telegram from EM 3 D was sent at 1040 to the Quentin Roosevelt at Bologne, with the following text:

No confirmed news from Nungesser aircraft since Sunday 0700 departure from Etretat on northwest route. Ministry orders searches. Do what is necessary for Roosevelt and escort to begin immediately, preferably along the east line Antifer-Beachy Head; boats from Cherbourg searching to the west. Confirm reception; report.

At 1110, still on May 10, the head of the Paris Navy HQ was informed of the state of the searches, and the information was concise:

Not able because of weather to carry out aerial patrols. Will be done as soon as possible by Latham Escadrille.

It would be tedious to continue the enumeration of the measures taken for the search, as they lasted through the days of May 11 and 12, 1927. On May 12 the presence of Léon Nungesser was reported aboard the Ailette. The newspapers were aware of the unfruitful searches. Le Petit Parisien, Le Populaire, and Le Quotidien of May 11 in particular give a list of the ships employed in the work. The local papers, like Le Havre-Eclair, talk a lot about it. Le Petit Parisien of May 12, as mentioned above, reports Léon Nungesser as declaring: “I have a feeling that my brother Charles is alive, that he landed Sunday off Etretat and is still floating on the sea;” and Le Havre-Eclair of the same date reports that Léon Nungesser was received by the Vice-Admiral, CIC Navy Cherbourg.

The conservator of archives of the first Naval District also has a photocopy of a note addressed on May 12 to the administration of seaboard conscription at Douarnenez by the Head of the Naval Division at the Naval District of Cherbourg, the text of which says:

I have the honour of informing you that the area situated to the north and northeast of Cherbourg has been patrolled the last few days in particular by a number of warships in the course of searching for Nungesser’s aircraft, and that no trace of the wreckage has been reported by the Admiral Troude or by the ketch Telen Mor, nor recovered.The searches stopped on May 12 in the evening; soon after which Léon Nungesser boarded a train for Paris.Of course, all of this work on the issues of the watches and searches does not prove that the aircraft did not crash into the Channel.

Examination of the Reports from the End of 1980.

In the light of what has been reported above, it is appropriate to look at the new testimony which became public knowledge at the end of 1980. We will first return to the article published in the newspaper Le Matin in December 1980, under the by-line of M. Bernard Veillet-Lavallée. It begins with a statement by M. Joseph Meny who was on the cliff on May 8, 1927 around 6 a.m. and who says: “Looking up, I saw an aircraft which seemed heavily loaded and which was jolting about. I thought to myself, ‘well, that won’t go far.’” We note at the outset that M. Meny doesn’t speak of bad weather – rain, wind, or fog. He watches the aircraft disappear over the waves, reports M. Veillet-Lavallée, and if M. Meny doesn’t say anything, it is because he thinks his testimony will not be acceptable to the unanimous jingoism[1] which accompanied the attempt.

Nothing contradicts M. Meny’s sighting of l’Oiseau Blanc, although it did not overfly Etretat until 0648. It is possible that the “jolting” was the consequence of the turbulence over the cliffs as the aircraft passed, although it is difficult to know from the ground the effect of this phenomenon on an aircraft flying at an altitude of about 200 meters, and the meteorological conditions of the moment should not have generated such turbulence.

The second account reported was that of M. Robert Duchemin, which states that his father, “while piloting a 14 meter cutter, registered at Fécamp, had seen, one day in May 1927, the wreckage of a white airplane which the waves pulled under before his eyes off Etretat. He alerted the Naval District, which demanded that he say nothing to anyone about it.” In 1937, M. Augustin Duchemin, ill, confided his secret to his three sons. At the end of the article, it is reported that M. Augustin Duchemin did not see the wreckage the day of the departure (May 8, 1927), but the next day or the next.

Mr. Robert Duchemin, who made public his father’s testimony, was more than willing to respond to our questions. He confirmed the story which is a prominent part of the article cited above by M. Bernard Veillet-Lavalée, and one which was published in Le Parisien Libéré on November 28, 1980 under the signature of M. Denis Roger. However, he corrected the story of the presence of his brothers, by noting that his mother was also there when his father made his revelation.

He said that his father, who was accompanied by three or four of his fellow boatmen, did not say what the weather or the sea was on the day, but that since he was fishing, the weather must have been all right. His father did not see the airplane land and did not hear the sound of the airplane’s motor. He was about 150 meters away from the wreckage when it went under. He recovered no debris from the area. The wreckage was apparently empty, but if the members of the crew were prostrated unconscious in the cockpit, he probably could not have seen them. In any case he heard no call for help.

The boat was fishing off Etretat. His port of departure and return was Fécamp. The Naval Authority in Fécamp was informed by M. Duchemin when he returned at the end of the afternoon. He was ordered to say nothing about what he had witnessed. (One notes that the Naval District of Fécamp did not find any documents at all concerning the Nungesser-Coli attempt in a search of their archives.) Mr. Robert Duchemin thinks that another boat crew may well have seen the landing or crash.

We recall from above that Léon Nungesser himself feared a landing in the Channel. All the newspapers talked abundantly about the searches undertaken and continued in vain, and the local papers ran the details on the front pages of their editions. Note in particular Le Havre-Eclair of May 9 recalls the military air cover guaranteed for the day of departure, and Le Havre-Eclair of May 11 follows up, in a dispatch from Cherbourg dated May 10, reports that “the mission entrusted to the Navy from the tug boats, torpedo boats, and hunter submarines, to the gunboats of the surveillance flotillas; to fishermen, navigating between Barfleur and the English coast and Cape D’Ailly [not far from de Dieppe–CPM] was carried out unsuccessfully; no airplane and no wreckage were seen.” This same edition of Le Havre-Eclair, in a first page article of two columns, states: “One asks oneself if they (Nungesser and Coli) were able to get very far, and if they were not fallen into the water of the Channel.” We can only regret that M. Augustin Duchemin did not make his statement at the time, for this would have without doubt have led immediately to the conducting of much more precise and thorough searches.

We have seen from the preceding that the searches were begun on May 8. Probably by May 9, and certainly by May 10, no one on the coast was unaware of them. Besides the specific searches undertaken, it is evident that other boats sailed to carry numerous volunteer observers from the stream of stories in the newspapers and on the radio about the possible disappearance of l’Oiseau Blanc in the Channel.

Let’s get back to the observations of the National Weather Bureau for the month of May, 1927. On May 8, the observations at 1300 and 1800 GMT, from stations cited above, show that the weather was a little overcast, except at la Hague and at Chausey, but that the wind rather had a tendency to diminish, and the visibility was better except at Cherbourg. The sea state remained calm.

For the next day, May 9, we have Table 3, still at 0700 GMT.

Table 3 W3.3m/s

(12 km/h)

(7 km/h)

(12-19 km/h)

(12-19 km/h)

In this general fashion the weather evolved little in the course of the day: visibility tended to diminish, except at La Hague where the fog lifted between 0700 and 1300; and the winds to grow very slightly stronger. The sea state was stable except at Cherbourg where one notes a coefficient of 6 at 1300. For the next day, May 10, there is this table, also at 0700 GMT (Table 4).

Table 4 Station Abbeville

(20 km/h)Le Havre

(14 km/h)Cherbourg

(14 km/h)La Hague

(20-28 km/h)Chausey

(20-28 km/h)The change for better in the weather in the course of the day was general except for Cherbourg; the visibility at Chausey lifted to 12 km between 0700 and 1300 and was maintained. At Cherbourg one notes that the sea state had a coefficient of 3 at 0700, of 4 at 1300, and of 6 at 1800. It is noted in the remarks on the form that the peaks of wind were blowing in a storm from 0900 to 2100; the wind average was 4 m/s to 12 m/s between 0700 and 1300, and steady.

Let us recall that Nungesser and Coli apparently finally took off without carrying any safety equipment (Robert de la Croix, They Flew The Atlantic, op.cit.), although Jacques Mortane, in his article published in Nº 97 of Journal des Voyages of May 19, 1927, says of Coli on the morning of May 8, that one could see a safety belt under his clothing. If the crew members had been killed (or badly injured to the point that they were both unconscious) by the shock of a very hard landing, then without doubt the aircraft would have been badly damaged and would not float very long. We must then think they were no longer on board since M. Duchemin did not receive any signal. Why would they leave their floating machine for the risk of swimming? Certainly the water was not very cold, but their chances of survival and rescue were much better if they remained with the wreckage until the last moment.

Let us note finally that for the wreckage to remain on the surface of the sea for 24 or even 48 hours (since M. Duchemin did not see this wreckage on the day of the departure) causes some problems. But the possibility that l’Oiseau Blanc turned around should not be excluded, even with all these circumstances.

Although the weather situation and the outfitting of the aircraft would definitely have permitted the crossing of the Channel, it is necessary to take into account the possibility of an engine failure, either shortly after Etretat, or later, during the return leg of the hypothetical turn-around of the aircraft. But contrary to what the author of the present account thought at the beginning of this examination, in spite of the declarations of the witnesses published at the end of 1980 and repeated at the beginning of 1981, reported above, it was necessary to further examine the records.

The Flight Over the Channel

Among the reports of the flight of l’Oiseau Blanc which appeared in the newspapers of the time, we note that one of the ones reproduced in the newspaper La Presse on May 13, 1927, makes reference to the following press release from the British Admiralty:

London, May 12. – The British Admiralty have published the telegram below received from the base commander of Portland (England): The submarine H.50 conveys an account of seeing an aircraft at 50°29′ north by 1°30′ west at 0745 British summer time on May 8, altitude 300 meters. Course about 300°. Light colored biplane. The only markings visible were red, white and blue on the tail. The biplane looked like one with a large fuselage. The visibility was not more than two or three miles. Weather too foggy to see other marks.

This message is very interesting because the position named is near the coast of England. Furthermore, one might hope (barring some of the bombings from the last war which had ravaged the archives of the Royal Navy) to have a good chance of finding some trace of this in Great Britain. A letter was immediately sent to London. Very shortly thereafter a response came from the Naval Historical Branch of the Ministry of Defense, dated May 13, 1981. This letter confirmed, in the following translation, the existence of the press release above, published also in The Times:

It is confirmed that the Admiralty did indeed publish a communiqué on the subject of possible visual contact with l’Oiseau Blanc by the submarine H.50. This was cited in its entirety on page 14 of the May 13 1927 issue of The Times [actually, the May 12 issue – CPM].

How could one persist in doubting that l’Oiseau Blanc crossed the Channel? For the position of the submarine H.50 (not far from the Isle of Wight) was crucial (see the detailed map of the Channel). If Nungesser and Coli’s aircraft had arrived at this point at 0745 (summer time), all the information about a possible crash in the vicinity of Etretat was definitely put to rest – unless l’Oiseau Blanc had turned around.

The second letter from the Naval Historical Branch is dated June 2, 1981. The consultation of the archives showed that there was no mention of visual contact with l’Oiseau Blanc in the log from the submarine H.50; however, the log did show a trip from the Thames to Portland on the morning of May 8. It is important to remember that the communiqué showed the telegram came from the base commander of Portland. The absence of a notation in the log book is not, in fact, abnormal. The H.50 knew about the request for look out which was sent by radio and newspaper to the ships at sea (see chapter 4); it is doubtful that the Royal Navy gave such orders. The observer almost certainly found himself in the conning tower on the surface, keeping surveillance over the sea and the sky for the proper safety of the H.50, because the ship traffic was without doubt heavy in the area. He saw a plane, but did not judge it necessary to make an official note of observation. The observer surely knew his own position with great precision. As we will see later, the information probably did not leave the Portland base until May 11, when the disappearance of the the aircraft was certain.

After various remarks on the possible confusion between GMT and summer time, and on the position of the H.50, the letter from the Naval Historical Branch ended this way:

The indicated times are probably official times (in this case, summer time), which was GMT + 1 (nowadays UT + 1). In fact, the letter indicates that there is no way of knowing with certainty if the time used in the log book was A or Z (A = summer time, Z = GMT), but the usual practice was to use the former. The reconstruction of the course of the submarine H.50, the hour of the sighting, and the longitude give in La Presse are not compatible (see the map). Therefore it appeared to be necessary to verify if the text of the communiqué from the British Admiralty which was published in The Times was the same as that which appeared in La Presse. Attentive reading of the documents and publications almost always shows discrepancies, and it is important to assure cross-checking wherever possible.If you wish to reconstruct the course of the H.50, you may use the elements below:

0700 270° (true) 9.6 NM in the

preceding hour0800 270° 8.6 NM 0828 290° 0900 290° 9.0 NM 0951 300° 1000 Passing of the

Portland jetty8.8 NM We use the word survol [lit. overflight or over-vision–Ed.] throughout in the sense of “visual contact” rather than “overflight.”

The Times of May 12, 1927, published under the sub-title “British Submarine’s Report” the press release the translation of which follows:[2]

The Admiralty recevied a telegram yesterday from the Captain-in-Charge, Portland, saying that Submarine H 50 had reported that at 7.15 a.m. (British Summer Time) on Sunday a biplane of light colour, with red, white, and blue markings on the tail, had been sighted over a position 50° 29′N., 1° 38′ W. [approximately 20 miles S.W. of the Needles]. It was flying at 1,000 ft. and its course was approximately 300° [approximately N.W. by W.]. It appeared to be a land machine with a large fuselage. The weather was too misty for the accurate colour of the markings to be seen.The resumé of the press release which was reproduced in this same issue under the heading “Today’s News” repeated the points “20 miles SW of the Needles” and “7:15.” A disagreeable surprise: the time and the longitude mentioned are different from those published in La Presse:The research became so complicated that in pursuing the reading of the daily newspapers, it appeared that l’Excelsior, Paris-Sport, Le Journal, and Le Quotidien of May 12 and Le Temps of May 13 reprinted the words of The Times, and Paris-Soir and l’Intransigeant of May 13 reprinted those of La Presse, as if two sources existed issuing different information. The official release from the General Commissioner of Aeronautics published a telegram from the French Air Attache in London indicating 0715 (see chapter 4).

La Presse: 0745 (summer time) 50°29′N 1°30′W The Times: 0715 (summer time) 50°29′N 1°38′W The release published by The Times gave a precise additional detail of importance: at the moment of the sighting, the point was situated at 20 miles (nautical or land? It isn’t very important – see the map) to the southwest of the Needles, which are at the extreme west end of the Isle of Wight. Was this additional detail in the release from the admiralty, or had it been added by The Times? On the other hand, Le Quotidien of May 12, in a two part article, the second part reproducing the Admiralty release, says that the submarine H.50 saw a clear colored biplane “in the neighborhood of 30 miles to the south of the Isle of Wight.”

To recapitulate, one notices that the base commander at Portland transmitted his telegram to the British Admiralty on May 11, 1927; the Admiralty published its release on May 12; The Times reproduced the release on May 12, and the French papers on May 12 and 13. The question is then: what were the sources of the French papers (the release from the Admiralty or the agency)? Where did the discrepancy about the time of sighting and the longitude come from, the precision of Le Quotidien seemingly having to be put aside?

One thing is absolutely clear: if the time of the sighting by H.50 (20 miles to the southwest of the Needles) is 0715 (summer time), the aircraft seen CANNOT POSSIBLY BE L’OISEAU BLANC, for it would have had to cover the distance from Etretat to H.50 at a groundspeed bordering on 380 km/h.

A new letter to the Naval Historical Branch in London asked if the archives still contained the release which was published by the British Admiralty. On a negative response (nothing in the archives of the Royal Navy, and also the archives from the time at Reuter and at the Press Association), and on the advice to broach the subject of the search with the British Public Record Office, the Air Attache at the French Embassy in London was brought in. His research also resulted in nothing (letter dated October 22, 1981). The Public Record Office at Kew in Richmond was approached, but found nothing in its Admiralty archives nor in the archives of the Ministry of Transport.

These fruitless investigations bring us no closer even to the existence of the release. It is therefore important to attempt to reconstruct the original text since the evidence shows that the ones we have read originate from at least two versions. We will refer to the map to clarify the statements below.

Given the details appearing in the letter from the Naval Historical Branch, we have reconstructed the route of the submarine H.50 between 0600 UT (0700 summer time) and 0900 UT (1000 summer time). Let us remember that the vessel’s speed was on the order of nine knots and that the courses indicated are true. The possible errors in tracing this route have negligible consequences for our purposes. The longitudes given by La Presse and by The Times are incorrect, whether the time of sighting was 0615 UT or 0645 UT, given the position of the H.50 at those times. On the other hand, the supplemental information, which figures in The Times but not in La Presse fixes the point of the sighting at approximately 20 miles southwest of the Needles. Now we see on the map that this twenty miles (nautical or land) brings us to a point not too far from the position of the submarine H.50 at 0645 UT. The more normal position is that obtained using nautical miles, if the information came from the Royal Navy release. If it was calculated by The Times (which is probable, for the corresponding information is between brackets, like that which accompanies the 300° course, while the note by the reference to the time is between parentheses [see the text which reproduces the exact presentation of the original of The Times]), it did not originate from the erroneous geographical coordinates published. It is possible that these errors are not, finally, typographic misprints. (For example, in The Times, 4 and 1 are numbers which it is possible to confuse.) If The Times itself changed the geographical coordinates of the release to angle/distance coordinates to render the information clearer, they would also have used nautical miles. On this same map, the 300° true course of l’Oiseau Blanc is traced from Etretat.

Throughout the preceding line of reasoning, we go on the assumption that the time used in the log book of the submarine H.50 (namely summer time) is known for certain. But it is still necessary to look at the consequences of the possible use of Universal Time (GMT). Arrival at the dike of Portland would then be about 1000 TU, instead of 1100 summer time. Referring to the map, we systematically correct the times mentioned for the course of the submarine, but not the times given in La Presse and The Times, because the times of reference were very clear in the press release. One sees then in this hypothesis, that the position of the submarine at 0615 UT would be close to that given in The Times’ release, but very far from the position situated at 20 miles to the southwest of the Needles (it is closer to a position situated at 12 NM to the south of the Needles). In this same hypothesis, the position of the submarine at 0645 UT was to the west of the position of the coordinates given in The Times, and therefore closer to the position 20 miles SW of the Needles, but still quite far from the latter. Thus, if the time used for the bearings of the submarine H.50 is Universal Time and not summer time, it is still the time of 0645 UT (or 0745 summer time) which gives the position that most closely approaches that indicated to the southwest of the Needles.

For the author of this report, it is therefore very probable that the sighting from the submarine H.50 took place at 0645 UT at about 20 nautical miles southwest of the Needles, and that it was indeed l’Oiseau Blanc which the submarine saw and described, along a course of 300° true which comes directly from Etretat. This conviction is essentially supported on the one hand by the fact that at least three newspapers, as we have said above (La Presse, Paris-Soir, and l’Intransigeant), mentioned 0745 summer time; and the other hand that it is not conceivable that an authority as prudent as the Royal Navy could circulate four days after the sighting a communiqué as clear and complete, although careful, as the one indicated above, without having verified that it could not have been a British aircraft (this verification was even mentioned), and that it was not impossible for it to be l’Oiseau Blanc.

Another element pleads in favor of this sighting. The communiqué from the Admiralty published in The Times says, as we have seen, that the aircraft seemed to be a land machine with a large fuselage. The observer is used to seeing seaplanes with floats and aircraft with wheels. Whether he knew or did not know the aircraft’s description, which was broadcast by French radio stations, his testimony is perfectly adaptable to l’Oiseau Blanc, which had neither wheels nor floats apparent and a fuselage with a fairly large diameter (see diagram of aircraft). The hypothesis advanced by Le Journal of May 12, 1927, which states emphatically that it was not l’Oiseau Blanc but the Lioré-Olivier machine of the aviator Denis, who “had accompanied Nungesser and Coli for some hours and landed at 7:15 at Droyden aerodrome,” is extremely doubtful, even if we postulate that the time really was 7:45; none of the newspapers, magazines or books examined allude to such a statement from Denis about a crossing of the Channel in company with l’Oiseau Blanc, a statement which would certainly be normal, at least to reject the hypothesis of a crash in the sea off Etretat, which was much discussed in the newspapers.

It is not completely excluded that the report of a sighting at 0715 summer time was mentioned in the communiqué, although it remains unlikely, because this point may have come, as we said, from an undetected error in typing or printing. Of course it is astonishing that no connection was made, or so it seems, to the Royal Navy’s communiqué, even though it was summarized in a telegram originating with the French Air Attache in London, and published by the General Commissioner of Aeronautics. Without doubt, this is because of the fact that after May 13, most of the newspapers seem to have admitted that sightings had indeed taken place in Ireland. But also, Commissioner Lahure was himself perhaps pre-occupied with the messages received from across the Atlantic – that is to say, the ones which falsely announced the success of the attempt. But it is nevertheless surprising that there was no reference to this report in the newspapers which appeared later (except for the error on our part, of course). If, subsequent to the publication of the communiqué, the British Admiralty was able to account for the matter as not l’Oiseau Blanc, it is possible that there was an official notification which the newspapers did not bother to print; or if they did print it, which this author did not find. To remove this doubt, it would be necessary to do meticulous research in the British daily newspapers. The Naval Historical Branch advises us, moreover, to attempt this sort of research, and its letter of July 31 indicates that The British Newspaper Library possesses most of the national and regional newspapers, and could be a good source for the clarifying the variations of the British Admiralty communiqué.

The historical service of the Navy was consulted, and did not find a single document which permitted us to think that the communiqué from the Royal Navy was the object of an official message to the French Navy.

| Translator’s Note | Introduction | Chapter 1 | Chapter 2 | Chapter 3 |

| Chapter 4 | Chapter 5 | Chapter 6 | Supplement | Acknowledgements |