| A Smoking Gun At Last? |  |

|

A Research Update From Ric Gillespie Our efforts to solve the riddle of Artifact 2-2-V-1 have taken a startling turn that has us on the edge of our seats. That bent, bruised and abused piece of aluminum may be the smoking gun we’ve been looking for. A chronology of recent research tells the story. |

|

| A torn section of aircraft aluminum was discovered by TIGHAR in 1991 during our second expedition to Nikumaroro. |

March 28, 2014

An investigative commission of ten TIGHAR researchers worked with the Restoration Staff at the National Museum of the United States Air Force to determine whether Artifact 2-2-V-1 can be matched to any of the museum’s WWII types that served in the Pacific. No match was found and it was the consensus of the researchers that the structure of the artifact strongly suggests that it came from a smaller aircraft than the combat and transport types inspected. That was the good news.

The bad news was that new information from experts in aircraft structures and repair made it apparent that the location on the belly of Earhart’s Electra that seemed to be the best fit could not, in fact, have been repaired in a way that would match the artifact. If 2-2-V-1 came from the Earhart Electra we would have to find a better fit some place on the aircraft.

A new line of investigation was also identified. Lockheed painted the interior surfaces of all Electras with aluminum paint as a corrosion inhibitor. WWII aircraft were painted with yellow-green zinc chromate. If aluminum paint could be found on the interior surface of 2-2-V-1 it would support the hypothesis that the artifact came from a pre-war Lockheed aircraft.

For the full commission report see “The Riddle of 2-2-V-1.”

April 7, 2014

I delivered 2-2-V-1 to Dr. Jennifer Mass at the Winterthur Analytical Lab in Greenville, Delaware, for testing to see if paint was present on the artifact.

May 30, 2014

Ric Gillespie checks his micrometer with New England Air Museum curator Mark Holby beside the museum’s Lockheed Electra. Photo by W. Mangus.

With the help of three commission members I examined Lockheed Electra c/n 1052 at the New England Air Museum in Windsor Locks, CT to see if we could find a new location that matches the rivet pattern on 2-2-V-1. We couldn’t. The inescapable conclusion is that the artifact can not have come from any area of original construction on a Lockheed Electra nor could it have come from a part of Earhart’s plane that was repaired by Lockheed.

It seemed like we were out of options. Whatever airplane the artifact came from, it apparently wasn’t Earhart’s. Close, but no cigar. Disappointing. Baffling. Frustrating.

June 5, 2014

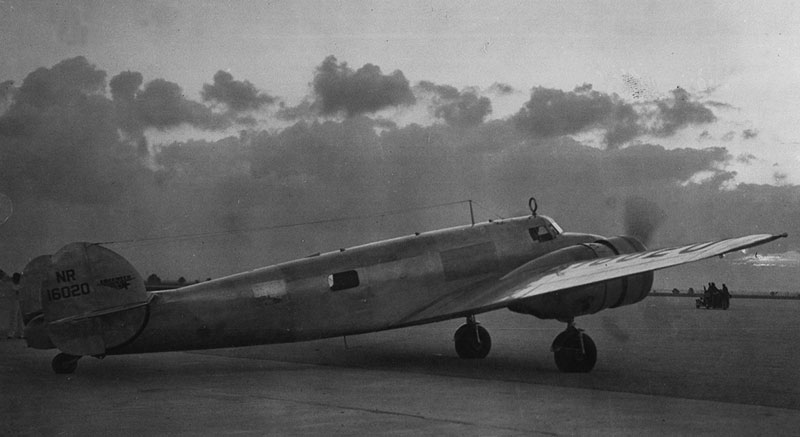

After reading the report on the trip to Connecticut, commission member Jeffrey Neville sent me an email wondering about the patch that was fabricated and installed in Miami to replace a large, special window that had been added to Earhart’s Electra prior to her first world flight attempt. Jeff noted that, because it was a field modification, it’s a complete wild card – the only place on the airplane that was not built or repaired by Lockheed. The materials (metal and rivets) would have to be the same as the rest of the airplane, but the rivet pattern on the patch was, by necessity, different from the standard structure – as unique to NR16020 as a serial numbered component. If, by some crazy chance, the dimensions of the artifact fit within the dimensions of the patch and we could match the rivet pattern on the patch to the distinctive rivet pattern ion the artifact, we would have a conclusively identified piece of Amelia Earhart’s airplane that was found on Nikumaroro – the definition of a smoking gun.

But what are the chances that the one piece of intact airplane skin we’ve found on the island in twenty-six years and ten expeditions is that patch? It seemed like a Hail Mary pass, a desperate attempt to somehow link 2-2-V-1 to the Electra after everything else had failed.

In late February or early March 1937, as one of the modifications made to the Earhart Electra in preparation for her world flight, a special, larger than standard, window was installed on the right hand side of the airplane. TIGHAR collection.

The window was there when Earhart arrived in Miami on May 23, 1937, the fourth stop on her second world flight attempt. Earhart remained in Miami for eight days while adjustments were made to her aircraft by local PanAm mechanics. When she departed for San Juan, Puerto Rico on June 1, the window had been replaced by a shiny aluminum patch. Miami Herald photo, used by permission.

June 15, 2014

In February, I had to cancel a scheduled speaking engagement at the New England Air Museum due to an ice storm. The museum director and I agreed to reschedule for Father’s Day. I brought the artifact along and, during a break, taped off the area of the fuselage on c/n 1052 where the patch had been on Earhart’s plane. I commandeered an unsuspecting museum visitor and had him hold the artifact up for a quick and dirty check to see if it fit. It did. The possibility that 2-2-V-1 might be the patch started to look less crazy.

June 22, 2014

Dr. Mass reported that after trying several different techniques she was unable to find any trace of paint on the interior surface of 2-2-V-1. She thought I would be disappointed because at the time I gave her the task we were hoping that she would find aluminum paint. In the interim, however, our hypothesis changed and the lack of paint is good news. It seems unlikely that whoever fashioned and installed the patch in Miami would bother to paint the inside surface.

June 23, 2014

The crucial piece of information, of course, is whether the rivet pattern on the patch matches our artifact. The trouble is, none of the several photos that show the patch have sufficient resolution to see the lines of rivets. The best photo is one that was taken by a Miami Herald reporter on the morning of June 1, 1937 (see above) as Earhart and Noonan taxied out for the public beginning of their world flight. The new patch where the window had been is bright and shiny but no rivet lines are discernible. Time to call in our forensic imaging expert Jeff Glickman, but first I needed to get Jeff the best possible copy of the image to work with.

Early in the project, as part of an effort to collect all known photographs of the Electra, we had gotten an 8x10 print of the photo from the Miami Herald who still own the copyright. On June 23rd I emailed the newspaper asking if they still had the original negative. Unfortunately they didn’t. The best they had was a scan that wasn’t as good as the print we already have, but they also found scans of two other photos that turned out to be useful.

This shot of AE with an unknown woman was taken in Miami before the window was replaced. Miami Herald photo, used by permission.

In this photo of the Electra taking off on June 1, the patch is clearly visible. Miami Herald photo, used by permission.

July 5, 2014

Jeff Glickman received the print of the “taxiing out” Miami Herald photo and reported:

This photo appears to be a print from a negative, possibly a first generation print from an original negative, although this is yet to be conclusively determined. The print does not suffer from a loss of information due to half-toning, nor does it have any digital compression artifacts. However, given the time period for the photographic chemistry, the grain size is large relative to the rivets, which are the objects of interest. I will be working over the next several days to determine what specific structures within the window patch can be discerned.

Needless to say, we are eagerly awaiting Jeff’s findings. We’re prepared to be disappointed. We have lots of practice. As he cautions, he may not be able to pull out enough detail to answer our questions. If he is successful in seeing the rivet lines they may be different from what we see on 2-2-V-1. In that case, the hypothesis fails and the artifact returns to the realm of the unknown. But if the rivet lines can be seen and if they do appear to match the artifact we’ll need to proceed with great caution to make sure that our findings are sound before we draw any firm conclusions.

Please note: The Miami Herald holds the copyright on the photos shown here of the Electra in Miami. The newspaper has generously given TIGHAR exclusive permission to publish the photos in research updates and on our website. All others must receive permission from the Miami Herald before publishing the photos. To request permission contact the Miami Herald’s licensing vendor, PARS International, at http://www.mcclatchyreprints.com or call (212) 221-9595.

|

Copyright 2021 by TIGHAR, a non-profit foundation. No portion of the TIGHAR Website may be reproduced by xerographic, photographic, digital or any other means for any purpose. No portion of the TIGHAR Website may be stored in a retrieval system, copied, transmitted or transferred in any form or by any means, whether electronic, mechanical, digital, photographic, magnetic or otherwise, for any purpose without the express, written permission of TIGHAR. All rights reserved. Contact us at: info@tighar.org • Phone: 610.467.1937 • JOIN NOW |