|

Earhart Project Research Bulletin #71

May 22, 2014

The Riddle of Artifact #2-2-V-1 |

| Since its discovery on Nikumaroro in 1991, TIGHAR Artifact 2-2-V-1 has been the subject of intense scrutiny and strident controversy. Is this battered sheet of aluminum a piece of the surf-shattered carcass of Amelia Earhart’s Lockheed Electra or is it a relic of some other Pacific aviation tragedy? To get closer to an answer, TIGHAR solicited the interest and assistance of the Restoration Division of the National Museum of the United States Air Force at Wright-Patterson AFB, Ohio. On March 28, 2014, a ten-person TIGHAR investigative commission met with the Restoration Division staff at the NMUSAF and examined a wide variety aircraft in the collection. This is what they learned. |  |

| Please note: this document will take a little while to load completely as there are many images. Please be patient! | |

|

Report of TIGHAR’s Artifact 2-2-V-1 Commission on Research Conducted at the National Museum of the United States Air Force Friday, March 28, 2014 |

| Members of the Commission | |

| Commissioner Ric Gillespie Executive Director, TIGHAR Oxford, PA |

Mark Appel, TIGHAResearcher #3564R Aptos, CA |

| Monty Fowler, TIGHAResearcher #2189R Huntington, WV |

Greg Hassler Restoration Supervisor, NMUSAF Wright-Patterson AFB, OH |

| Karen Hoy, TIGHAResearcher #2610R DeSoto, TX |

Jeffrey Lange, TIGHAResearcher #0748R Ypsilanti, MI |

| LTC William Mangus USAF (ret) TIGHAResearcher #3054R Montclair, VA |

Jeffrey Neville, TIGHAResearcher #3074R Brooklet, GA |

| Lee Paynter TIGHAResearcher #3314R Atglen, PA |

Aris Scarla Grand Rapids, MI |

|

| Members of the Artifact 2-2-V-1 Commission L to R: Jeff Neville, Ric Gillespie, young photo-bombing museum visitor, Jeff Lange, Karen Hoy, Lee Paynter, Bill Mangus, Aris Scarla, Michelle Martin, Mark Appel. Not shown: Monty Fowler, Greg Hassler. Aircraft is a Lockheed C-60A Lodestar. Photo courtesy J. Neville. |

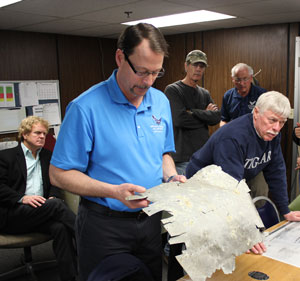

On March 28, 2014, TIGHAR’s Artifact 2-2-V-1 Commission conducted research at the National Museum of the United States Air Force at Wright-Patterson AFB, Ohio. The Commission’s access to the museum’s restoration hangars, which are located on the active air base, was hosted by Commission member Lt. Col. William Mangus USAF (ret).

Acknowledgements & Caveats

|

| L to R: Lee Paynter, NMUSAF Restoration Supervisor Greg Hassler, Mark Appel, NMUSAF Restoration Division Chief Roger Deere, Ric Gillespie. Photo courtesy W. Mangus. |

During our visit, TIGHAR enjoyed almost unlimited access to the museum’s aircraft, materials, and expertise. We want to thank NMUSAF Restoration Division Chief Roger Deere and Restoration Supervisor Greg Hassler for their hospitality and enthusiastic participation in our research. We also extend our sincere appreciation to Restoration Volunteer Garry Guthrie, who devoted his own time to research prior to our visit and accompanied us throughout our entire day at the restoration hangars and in the museum.

|

| L to R: Ric Gillespie, NMUSAF Restoration Volunteer Garry Guthrie. Photo courtesy W. Mangus. |

The Commission is comprised of 10 volunteers, most, but not all, of whom are TIGHAResearchers. Three members of the Commission are aviation professionals with extensive knowledge and experience in aircraft construction, maintenance, and repair practices. Aris Scarla is the manager of the FAA Flight Standards District Office in Grand Rapids, Michigan, but his work on the Artifact 2-2-V-1 Commission is as a private individual and his opinions should not be construed as official findings by the FAA. Similarly, Greg Hassler is the Restorations Supervisor for the NMUSAF but his opinions should not be construed as official findings of the National Museum of the United States Air Force. Jeffrey Neville is an executive with Gulfstream Aerospace Corporation but, as with the others, his service to the Commission is as an individual volunteer, not as a representative of his employer.

Stated Purpose

The purpose of the Commission’s visit to NMUSAF was to collect data and solicit expert opinion that will help TIGHAR test the hypothesis that Artifact 2-2-V-1 came from Amelia Earhart’s Lockheed Electra aircraft.

Background

|  |

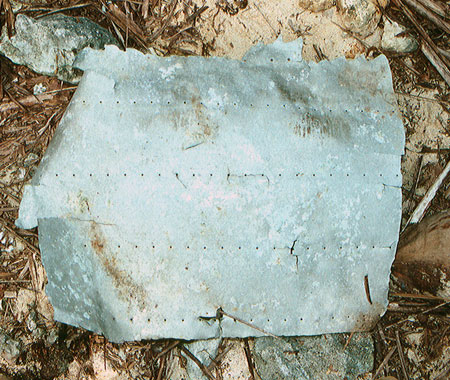

| Artifact 2-2-V-1 as found on October 18, 1991. TIGHAR photo by P. Thrasher. | Artifact 2-2-V-1 now. TIGHAR photo by P. Thrasher. |

In 1991, TIGHAR’s second expedition to Nikumaroro discovered a damaged piece of aluminum sheet lying among the vegetation and flotsam from a severe storm that had hit the island since our initial visit two years earlier. Cataloged as TIGHAR Artifact 2-2-V-1, the object has been the subject of intense scrutiny and analysis ever since. In the process of investigating 2-2-V-1 some parts of it have been sacrificed to destructive testing. Specifically, the National Transportation Safety Board Laboratory cut off a small piece for microscopic examination, and the ALCOA company cut out three rather large rectangular “coupons” in order to assess the composition and condition of the metal. As a consequence, the artifact today looks somewhat different than it did when it was first discovered.

Established Facts

The sheet measures roughly 19 inches wide by 23 inches long. None of the four sides is an original manufactured edge. Artifact 2-2-V-1 is a piece forcibly separated from a larger panel of aluminum aircraft skin.

|

| The metal failed sequentially from three distinct types of stress – lateral tearing along the line of 5/32″ rivets; then fracturing from a force perpendicular to the sheet surface; and finally fatigue from cycling back and forth against a crossing underlying structure. |

The edges of the sheet exhibit three types of failures. One long edge failed from lateral tearing; the other long edge and one short edge fractured due to the impact of a powerful fluid force on the interior surface of the sheet; the remaining short edge failed from fatigue after repeated cycling. The failures did not occur simultaneously in a single event. The artifact appears to be a piece of debris from an aircraft that was destroyed in a series of high-energy events over some period of time – perhaps minutes, perhaps hours, perhaps days.

|

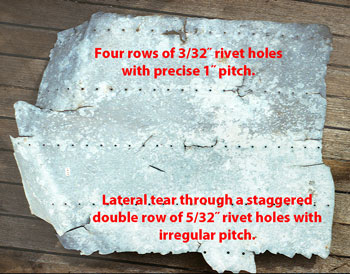

| The sheet is perforated with four rows of rivet holes 3/32″ in diameter with a precise pitch (interval between holes) of 1″. There is no crossing line of rivet holes. |

The sheet is made of a product introduced by Alcoa Aluminum in 1933 known as “24ST Alclad.” Earhart’s Lockheed 10E Special was skinned with 24ST Alclad. Nearly all American all-metal aircraft manufactured in the 1930s, during WWII, and afterward were skinned with this material.

The sheet is .032″ in thickness. Skins of that thickness were common on Earhart’s Lockheed and on many other aircraft.

The sheet is perforated with four rows of rivet holes 3/32″ in diameter with a precise pitch (interval between holes) of 1″. There is no crossing line of rivet holes.

One edge of the sheet failed along a staggered double row of rivet holes 5/32″ in diameter with irregular pitch.

|

The single surviving rivet is an AN455-AD “brazier head” rivet with a shaft diameter of 3/32″ (colloquially a “#3” size rivet). The “brazier head” has a low profile and was used on external surfaces to reduce aerodynamic drag.

The rivet has a shaft length of 3/16″ indicating that the underlying structure to which it was once attached was approximately .06″ in thickness.

Portions of the sheet have suffered a loss in ductility through exposure to heat – more heat than can be explained by simple exposure to intense sunlight, but not enough heat to melt the metal. Aluminum melts at 1,221°F. The loss of ductility in portions of the sheet is consistent with exposure to heat in the realm of 800°F such as might result from brief exposure to flame. A former resident of Nikumaroro has described cooking fish on a sheet of metal with many small holes.

This fragment of stringer from the wreck of Electra c/n 1024 in Idaho is .06″ inch in thickness and has #3 size rivet holes with a 1″ pitch. |

On the exterior surface of the sheet the letters “AD” are clearly visible and are presumed to be remnants of the original Alcoa labeling. On the exterior surface of the sheet the letters “AD” are clearly visible and are presumed to be remnants of the original Alcoa labeling. |

Although found on land, the sheet exhibits several areas of carbonate (coral) encrustation suggesting that it spent months and perhaps years submerged in relatively shallow water. Although found on land, the sheet exhibits several areas of carbonate (coral) encrustation suggesting that it spent months and perhaps years submerged in relatively shallow water. |

|

The “1940 Gardner Co-Op Store” was located near the head of the landing channel. This is how it appeared during TIGHAR’s first expedition to Nikumaroro in 1989. |

|||

The artifact was discovered in 1991 just inland from the head of the landing channel that was blasted through the reef when the island was abandoned in 1963. The artifact was discovered in 1991 just inland from the head of the landing channel that was blasted through the reef when the island was abandoned in 1963. |

|||

When TIGHAR returned to the island in 1991, the beach exhibited severe storm damage. Artifact 2-2-V-1 was discovered among the washed-up beachfront vegetation near the collapsed seaward-facing wall of the store. |

|||

Preliminary Criteria for an Aircraft-of-Origin

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

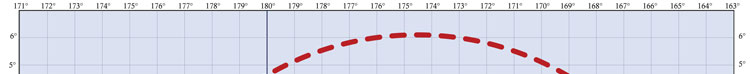

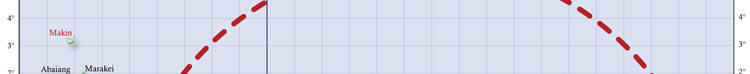

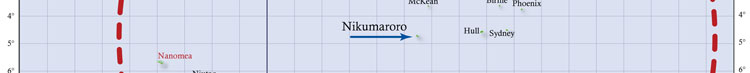

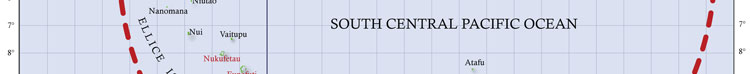

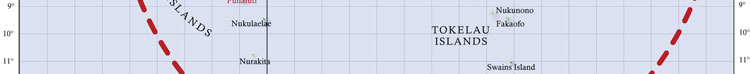

For the purposes of this discussion we have defined the South Central Pacific as the area encompassed by a circle 1,300 nautical miles in diameter centered on Nikumaroro where the artifact was found. Place names in red had airfields during WWII.

Artifact 2-2-V-1 is a section of the external “skin” from an aluminum airplane of American manufacture that was destroyed in a catastrophic event somewhere in the Central South Pacific.

There are twenty-eight known occurrences in which aircraft were damaged, lost or destroyed in the Central South Pacific. The aircraft types are:

- Bell P-39 ( 1 loss, 1942)

- Boeing B-17 (2 losses, 1942)

- Consolidated PBY (1 loss, 1940; 1 loss, 1942; 5 losses, 1943; 1 loss, 1944)

- Consolidated B-24/Navy PB4Y-1 (1 loss, 1943; 1 loss, 1944; 1 loss, 1945

- Consolidated C-87, cargo version of B-24 (1 loss, 1943)

- Douglas C-47 (1 loss, 1943)

- Lockheed 10E Special (1 loss, 1937)

- Lockheed PV-1/Army C-60 (1 loss, 1944)

- Lockheed l-749A Constellation (1 loss, 1962)

- Martin PBM (1 loss 1942, 2 losses, 1944)

- North American B-25/ Navy PBJ (2 losses, 1944)

- Sikorsky S-42B (1 loss, 1938)

It is, of course, possible that other aircraft types were lost or destroyed but not reported.

Questions Addressed by the Commission

- Would a detailed examination by experienced aircraft maintenance professionals reveal further clues about the artifact’s origin?

- Would a careful inspection of aircraft and materials in the NMUSAF collection provide further data on aluminum labeling practices?

- Would an inspection of aircraft in the NMUSAF collection representative of types that served in the South Pacific theater of war reveal structural patterns identical or closely similar to Artifact 2-2-V-1?

Findings

| 1. | Would a detailed examination by experienced aircraft maintenance professionals reveal further clues about the artifact’s origin? | |||||||||

| A detailed examination by Aris Scarla and Greg Hassler concluded that: | ||||||||||

| a. |

The pitch (interval between rivets) of the #3 rivets is precisely and consistently 1 inch. This level of precision suggests factory-quality work. By contrast, the pitch of the staggered double row of #5 rivets is irregular and was probably dictated by features in the underlying structure that had to be avoided.

|

|||||||||

| b. |

|

|||||||||

| c. | The missing rivets in 2-2-V-1 were not drilled out. The rivet holes exhibit none of the distortion that inevitably results from drilling. This again suggests that the holes were made either during original construction or during factory repair, not wartime field repair. | |||||||||

| d. | Most of the rivets failed in tension when a fluid force struck the sheet on the interior surface with sufficient energy to blow the heads off the rivets. Some pieces of the underlying structures (i.e. stringers) appear to have remained attached by a few rivets until being subsequently pried off by human action using a strong knife or similar implement. | |||||||||

| e. |

Zinc chromate did not come into common use in aircraft until the late 1930s. Earhart’s Electra, constructor’s number (c/n) 1055, the 55th Model 10, was built in the spring of 1936. Lockheed sales literature for the Model 10 Electra dated March 2, 1936, specifies that “Although its aluminum coating renders Alclad highly resistant to corrosion, every part of the interior of the airplane is painted for further protection.” A section of wreckage recovered by TIGHAR in 2004 from the crash site of Lockheed 10A constructor’s number (c/n) 1024, which flew into an Idaho mountain in December 1936, has aluminum-colored paint on the interior surface. A close examination of the interior surface of 2-2-V-1 reveals what may be surviving traces of aluminum-colored paint.

The section of known Electra wreckage in the foreground has aluminum-colored paint on the interior surfaces. Photo courtesy W. Mangus. |

|||||||||

| 2. | Would a careful inspection of aircraft and materials in the NMUSAF collection provide further data on aluminum labeling practices? | |||||||||

The existence of remnants of the original Alcoa labeling is remarkable and fortunate. Interpreting its significance is difficult and controversial. TIGHAR is no stranger to either of those adjectives. In 1993 we sought to learn what the letters “AD” on the artifact might signify. Matching the lettering style to labeling found on three aircraft – two Lockheed Electras and a C-47 – we concluded that the letters were probably part of a sequence that originally read “ALCOA R. T. .032″ ALCLAD 24S-T3 AN-A-13.” In 1996, while at ALCOA Aluminum’s laboratory near Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, for metallurgical testing of the artifact, we asked ALCOA engineers if they could help us with the meaning of the presumed sequence. They explained that the 24S alloy was first developed by ALCOA in 1933. The “T3” stands for a heat-treated tempering process that was introduced in 1937. “AN” stands for “Army Navy” – the standard prefix for all aircraft materials specifications in the U.S. regardless of whether they were used in military or civilian applications. The “A” stands for “Alcoa.” The “13,” they said, signifies that it is “reserve stock” sheet that has been certified for uses other than original construction. No documentation was offered to support their explanation.

Recent research by members of the on-line TIGHAR Forum suggests that the Alcoa engineers may have been mistaken in some respects. The AN-A-13 specification appears to have been introduced some time between 1941 and 1943 and has to do with the physical properties of the sheet rather than “reserve stock.” The actual specification has not been found, nor do we know whether AN-A-13 was ever on the artifact or when Alcoa started using the lettering style seen on 2-2-V-1. The lettering on aluminum seen in photos of several pre-war aircraft, including Earhart’s, is not like the “AD” on the artifact. So far, no example of the letters or lettering style seen on the artifact has been found on aluminum known to date from 1937. During the Commission’s visit, the NMUSAF staff pointed out examples of original labeling on aluminum from aircraft under restoration. Labeling on original aluminum from B-17F “Memphis Belle” included the word ALCLAD, but in smaller size and a somewhat different style than the AD on 2-2-V-1. No example of AN-A-13 labeling was found.

|

||||||||||

| 3. | Would an inspection of aircraft in the NMUSAF collection representative of types that served in the South Pacific theater of war reveal structural patterns identical or closely similar to Artifact 2-2-V-1? | |||||||||

| If our Preliminary Conclusion is correct – that Artifact 2-2-V-1 is a section of the external “skin” from an aluminum airplane of American manufacture that was destroyed in a catastrophic event somewhere in the Central South Pacific – then there must be someplace on some American aircraft that matches, or could be legally and reasonably repaired in such a way as to match, the materials, measurements, and rivet patterns of Artifact 2-2-V-1. Because the artifact was found on Nikumaroro, it follows that the aircraft-of-origin was a type that was present at some time in that part of the world. Due to the remoteness of the Central South Pacific, those aircraft types are a limited and known population.

During the Commission’s visit to NMUSAF, the members inspected 15 aircraft types known or suspected to have been present in the Central South Pacific before, during and after WWII. Each aircraft was examined by the entire team. We had to stay together because NMUSAF restoration shop volunteer Garry Guthrie had to be with us to reassure museum security personnel that the TIGHAR Commission members had official clearance to go beyond the barriers to examine the aircraft in detail. Individual rivets were measured with calipers. Rivet pitch and stringer spacing were measured with rulers. The only portions of the aircraft the commission members could not inspect were the top surfaces of wings and fuselages that would have required scaffolding to see.

The aircraft types examined were:

|

||||||||||

| Results of the Inspection | ||||||||||

| 1. | Several of the aircraft were entirely flush riveted and could be quickly eliminated. These included:

|

|||||||||

| 2. | #3 size rivets and brazier head rivets were not uncommon on the B-17, B-24, C-47 and B-18. | |||||||||

| 3. | Parallel rows of rivets were also not uncommon, but parallel rows of #3 brazier head rivets with 1″ pitch and spacing between rows similar to those on 2-2-V-1 were not found on any of the aircraft inspected. | |||||||||

| 4. | The closest matches were on the B-24, but not close enough to be considered possibilities for the origin of 2-2-V-1.

The rivet pattern on the underside of the B-24 horizontal stabilizer was somewhat similar to the pattern on 2-2-V-1. Photo courtesy J. Neville. |

|||||||||

| 5. | Beyond the quantifiable characteristics of the aircraft inspected, all of the Commission members, having spent an entire day paying close attention to the way various aircraft are constructed, felt that the “scale” of the combination of materials in Artifact 2-2-V-1 was wrong for the WWII aircraft they inspected. | |||||||||

|

||||||||||

Conclusions

With no firm answers to either confirm or disprove the hypothesis that Artifact 2-2-V-1 is wreckage from the Earhart Electra, any conclusions must be limited to quantifiable data that narrow the field of possible aircraft-of-origin and move the likelihood needle one way or the other.- Learning that rivet pitch does not change in a repair means that the artifact is probably not from the area on the belly of Earhart’s aircraft where we had thought it might fit. We need to find a better candidate area on the Electra (if there is one).

- On the other hand, the new information that the lines of rivet holes on the artifact do not converge or taper as previously thought and that the artifact is not necessarily from a repaired area present more possibilities for a match on the Electra.

- The discovery of a second D on the artifact gives us more information but until better data about aircraft aluminum labeling practices surfaces, the variety of labeling styles and content seen on museum aircraft precludes any definitive conclusions based on the letters visible on the artifact.

- The factory-grade precision of the workmanship in the rivet installation reduces the likelihood that the artifact was part of a field repair.

- The absence of any sign of zinc chromate corrosion inhibitor on the interior surface of the artifact and the absence of paint on the exterior surface argue strongly against 2-2-V-1 being part of any WWII aircraft serving or transiting through the Central South Pacific.

- The inability of the museum personnel and the Commission members to find a matching pattern on any of the aircraft inspected and their unanimous opinion that the general scale of the artifact suggests a smaller, more lightly built aircraft than any of the wartime types further lower the probability that 2-2-V-1 is from a WWII aircraft.

Refined Criteria for an Aircraft-of-Origin

Based on the research conducted at the NMUSAF on March 28, 2014, it is possible to refine the criteria for Artifact 2-2-V-1’s aircraft-of-origin. The available evidence now suggests that the artifact is probably not from a WWII combat or heavy transport aircraft and is probably from an airplane smaller and lighter than any of the military types that served in or transited through the Central South Pacific. If the artifact is from a repaired area, the repairs were probably done at the factory. The artifact is, without question, from an aircraft that suffered catastrophic damage somewhere in the Central South Pacific region. At present, of the known losses in the Central South Pacific, only Earhart’s Electra fits all of the requirements. Further research may yield additional information that will either support or refute the criteria.

What’s Next?

Laboratory testing is presently underway to determine whether there is paint on the interior surface of the artifact. If paint is found it will be compared to the paint on the interior surface of known Lockheed Electra wreckage dating from 1936.

Lockheed engineering drawings are currently being searched for areas on the Model 10 that may be reasonable matches to the artifact. In coming weeks Commission members will also inspect Lockheed 10A c/n 1052 and other aircraft at the New England Air Museum in Windsor Locks, CT for possible matches to 2-2-V-1

Several practical experiments are being designed to test whether the hydrodynamic forces present at Gardner Island (Nikumaroro) in early July 1937 were sufficient to cause the kind of damage evident on artifact 2-2-V-1.

Last Word

The net result of the Commission’s work is that the population of candidates for an aircraft-of-origin for Artifact 2-2-V-1 has been narrowed, and new avenues of investigation have been opened. Questions about labeling and the artifact’s possible location on the Earhart Electra remain, and the answers may ultimately disprove the hypothesis, but the process of scientific investigation continues.

I would like to personally thank all of the members of the Commission for the generous devotion of their time, energy, and intellect in the pursuit of an answer to the riddle of Artifact 2-2-V-1.

| Ric Gillespie Commissioner, Artifact 2-2-V-1 Commission Executive Director TIGHAR |

Careful measurement of the space between lines of rivets holes revealed that the lines do not taper or converge as previously believed – including by the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) Lab. There are, however, slight irregularities in the spacing between lines suggesting that the underlying structures, presumably stringers, were not precisely aligned. These irregularities suggest that 2-2-V-1 may be part of a repair.

Careful measurement of the space between lines of rivets holes revealed that the lines do not taper or converge as previously believed – including by the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) Lab. There are, however, slight irregularities in the spacing between lines suggesting that the underlying structures, presumably stringers, were not precisely aligned. These irregularities suggest that 2-2-V-1 may be part of a repair.