|

Artifact 2-2-V-1, Aluminum Sheet: New Evidence

On July 11, TIGHAR videographer Mark Smith and I spent the day with metallurgical engineers at Massachusetts Materials Research in West Boylston, Massachusetts. MMR are experts in the mechanical failure of metals. Our primary purpose was to learn as much as we could about the way each of the four edges of the artifact failed but, despite repeated attempts using Scanning Electron Microscopy, there wasn’t much they could tell us. The edges scrubbed around in sand and coral for so long that the information the metallurgists need had been obliterated. The day was looking like a bust until about an hour before we had to head for the airport. Looking for something more we could do, I raised a question that had been bothering me for a long time.

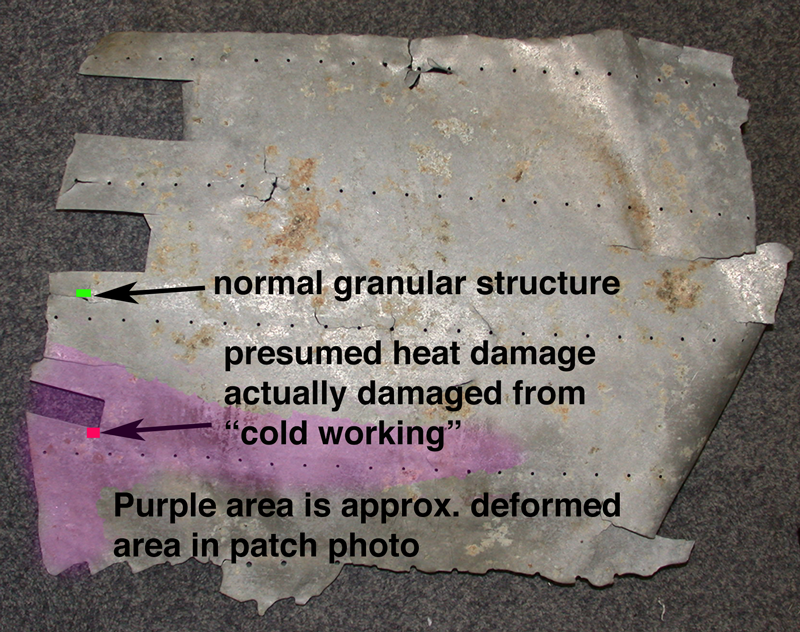

In 1996, ALCOA cut three large “coupons” out of the artifact for testing to identify the metal, confirming it is 24ST (today known as 2024) ALCLAD aluminum. They used tin snips to cut two parallel lines, then bent up the tab and cut the end. When they tried to bend up one tab, the end snapped instead of bending because the metal was more brittle in that area. The ALCOA engineers said that part of the artifact had apparently been exposed to intense heat at some time. This has always been puzzling. All we could think of is that the villagers must have used it to cook on – but then why wasn’t the whole thing heat damaged? The folks at MMR said they could determine for certain if that part of the artifact was more brittle than the rest and, if so, why. They cut two tiny specimens – one from the border of a “normal” coupon and another beside the presumably heat-damaged coupon. After testing, they found that the specimen from the damaged area was, indeed, significantly harder and more brittle. Microscopically examining the granular structure of the metal in both specimens, they found the cause of the brittleness was not heat but “cold working.”

When metal is repeatedly bent or “worked,” permanent defects are created which change its crystalline makeup. These defects reduce the ability of crystals to move within the metal structure and the metal becomes more resistant to further deformation. It becomes harder and more brittle. If the “working” continues, the metal breaks. Most people know this as “metal fatigue.”

The “working” had to occur while the artifact was still on an airplane. That’s obviously not supposed to happen on any airplane. Flying machines are designed to flex, but not bend and break. From photos of the patch on NR16020 we’ve known for some time that, toward the end of the world flight, the poorly designed patch was beginning to bend and buckle or, in other words “work.” In the 16mm film imagery, the deformation has become severe in the lower left part of the patch. We now have scientific proof that the lower left portion of 2-2-V-1 shows clear evidence of the kind of damage caused by the kind of plastic deformation we see on the patch.

Meanwhile, forensic imaging expert Jeff Glickman continues to make progress in applying cutting-edge “super resolution” software to the 16mm film images of the patch.

Click HERE to read the full report from MMR as a PDF.

|

|

| The patch, from the film taken in Lae New Guinea. | 2-2-V-1. |