|

Introduction |

|

The Mystery

One of the abiding historical mysteries of the twentieth century in the Pacific is that of “what happened to Amelia Earhart.” Earhart, a pioneer in American aviation, and her equally pioneering navigator Fred Noonan, disappeared on July 2nd 1937 en route from Lae, New Guinea to Howland Island in their two-engine aluminum Lockheed Electra 10E, during an attempt to circle the globe at the equator. Earhart’s last generally accepted radio message, received at Howland by the US Coast Guard cutter Itasca waiting offshore, indicated that she believed she was somewhere along a line bearing 157° – 337° , generally referred to as a “line of position” (LOP), running through the island’s charted location. Earhart said they were flying “on line north and south.” After their loss a vigorous search failed to find them, and in the decades since a number of hypotheses have been advanced for what happened to them.

Among the best known hypotheses is a set of overlapping propositions that they were captured somewhere in the Micronesian islands then under Japanese administration, and incarcerated on Saipan (or in one account Tinian) where in most accounts they died or were executed and were then buried.1 In this paper we attempt a systematic description, analysis and critique of the eight stories that in various configurations constitute the “Earhart-in-the-Marianas” hypothesis.

Figure 1: Main Locations Referred To (Source: Google Earth)

The Authors

In the interest of full disclosure, we acknowledge that we are active participants in the work of The International Group for Historic Aircraft Recovery (TIGHAR), which for the last 24 years has been collecting and analyzing evidence related to what we call the Nikumaroro Hypothesis – that Earhart and Noonan landed and died on Nikumaroro in the Phoenix Group, Kiribati. We think that the historical, archaeological, and other data we have collected strongly suggests that the Nikumaroro Hypothesis is correct. This fact will probably cause some proponents of Earhart-in-the-Marianas to reject the analysis reported here out of hand; we can do nothing about this. We can only assure readers that we have tried very hard to prepare this paper with open minds, and we ask that it be read in the same spirit.

The Sources

In preparing this paper we have reviewed all the books we could find positing that Earhart and Noonan were in the Marianas, together with a number of media accounts, letters, emails and manuscripts filed with TIGHAR; these sources are discussed below.

Boundaries on Our Research

We have limited our consideration to those stories that have Earhart and Noonan spending some time on Saipan and/or Tinian as captives of the Japanese. We have not dealt with stories about their capture and death in the Marshall Islands or Chuuk except where these stories involve their transport to Saipan. We have not considered those that put them in New Guinea or New Britain, or with those that have them being taken straight to Japan. Nor have we considered those notions that do not feature incarceration at all – for example the Nikumaroro Hypothesis or the hypothesis that Earhart and Noonan splashed down in the Pacific and sank.

|

| The Eight Stories

|

What we call the Earhart-in-the-Marianas Hypothesis is reflected in eight interrelated stories, though not all proponents of the hypothesis subscribe to all eight in all respects, and some more or less contradict others. The eight stories are:

- That Earhart and Noonan flew their Electra 10E directly to Saipan from Lae, New Guinea;

- That Earhart and Noonan landed elsewhere in Micronesia and were brought to Saipan;

- That the Electra was at Aslito Airfield (now Saipan International Airport);

- That Earhart (and in some versions, Noonan) was incarcerated at the Garapan jail;

- That Earhart was incarcerated or otherwise kept elsewhere on Saipan;

- That U.S. Military personnel found physical evidence of Earhart on Saipan and elsewhere in Micronesia;

- That Earhart and Noonan died or were executed on Saipan or Tinian, and were buried there; and

- That the U.S. government covered up the facts of the matter.

Below, we will examine each of the eight stories. |

| Earhart and Noonan Flew to Saipan |

The Story and its Evolution

There are several versions of the story that Earhart and Noonan flew the Electra directly from Lae, New Guinea to Saipan.

Paul L. Briand, Jr. published his account in his 1960 book Daughter of the Sky, The Story of Amelia Earhart. It is based on the eyewitness account of former Saipan resident Josephine Blanco Akiyama, who said that as a young girl she saw a silver plane fly over and later saw a Caucasian couple surrounded by Saipanese. She said the two were led away by Japanese soldiers, that shots rang out and the soldiers returned alone. Briand concluded that Ms. Akiyama had seen Earhart and Noonan; his book proposes that problems with navigation equipment during the night resulted in Earhart turning north instead of flying east, and that Noonan, either incapacitated or asleep, failed to correct the error. When the sun rose, Briand posits that they looked for land and saw Saipan. Being out of fuel, they ditched in the harbor at Tanapag, where they were captured by the Japanese and executed as spies.

Another version of the story was published in 1969 by Joe Davidson in Amelia Earhart Returns from Saipan. Davidson recounts the efforts of a group of investigators from the Cleveland, Ohio area led by Donald Kothera. They first tried to find an aircraft Kothera had seen on Saipan after the war, and which he thought, in retrospect, might have been Earhart’s, but also recorded the stories of residents. Davidson’s version of the “flew to Saipan” story was derived largely from the eyewitness account of Antonio Diaz, who said that in 1937 he was directed by the Japanese to help move a plane that had crashed into some trees near Tanapag Harbor at about 3:00 in the morning. Kothera and his colleagues showed Diaz pictures of Earhart and Noonan as well as the Electra; he said he thought they looked like the people and plane he had seen. Diaz said he thought the plane, which was not badly damaged, had been loaded on a ship in the harbor but he did not know what had happened to the fliers.

A third version of the story was told by Thomas E. Devine in his 1987 book Eyewitness: The Amelia Earhart Incident, and repeated in 2002 with elaboration in With Our Own Eyes by Mike Campbell (with Devine). Devine – a self-identified eyewitness to the Electra’s presence and burning at Aslito Airfield in July 1944 (see below), believed that weather and radio problems produced miscalculations that sent the plane north rather than east. Devine was convinced that Earhart and Noonan flew directly to Saipan, where they were captured and killed; Campbell seems a little less sure, and devotes considerable space to considering the alternative that the plane came down in the Marshalls and was brought to Saipan by the Japanese (see below).

The Evidence

As noted, Paul Briand’s primary evidence is the account of Josephine Blanco Akiyama, who said that as an eleven-year-old girl she saw a plane go down in Tanapag harbor, from which came a tall man and a woman with short hair and dressed like a man, the first westerners she had ever seen. In 1946 she related the story to her employer, a dentist for whom she worked; it made news in 1960 when it was published in the San Mateo (California) Times. Briand concludes that the “American woman and her tall male companion could have been none other than Earhart and Fred Noonan” (Briand 1960;196).

Joe Davidson mentions Ms. Akiyama’s story, which has the Electra ditching in Tanapag Harbor around noon, but he concentrates on the eyewitness testimony of Antonio Diaz, who has the plane landing near the beach at around three o’clock in the morning. Diaz said he did not see the plane land but the fliers were “one man and one woman wearing a jacket and pants.” He said their Japanese captors identified them as Americans, that they were not injured in the landing, and that he had no knowledge of what happened to them. He said the plane was hardly damaged except that it crashed into some trees, and he was engaged to help build a coral road to transport the plane from where it crashed to the harbor. This work, he reported, took two weeks, and the plane was then loaded aboard a ship. He said he was told that it was taken to Japan. The recollections of Antonio Diaz are the only reported evidence for this story.

The initial evidence for Devine’s version of events comprises his own recollections, which feature learning that the Electra was in a locked hangar at Aslito Field in July 1944, then seeing it in the air, and then seeing it on fire near the hangar. He said he clearly saw the plane’s serial number, NR16020, which became “etched in my memory.” He also reported being told about, and seeing, a gravesite said to be Earhart’s and Noonan’s. Some two dozen corroborating eyewitness and other accounts are presented in Campbell’s book. Neither Devine’s nor Campbell’s book provides evidence for the confusion aboard the Electra that Devine thought brought it to Saipan. Apparently Devine took the fact that he recalled seeing it there in flying condition as prima facie evidence that it had been flown there.

|

| Earhart and Noonan Were Captured Elsewhere and Brought to Saipan

|

The Story and its Evolution

In late 1960, the Office of Naval Intelligence ONI) assigned a Special Agent, Joseph M. Patton, to evaluate the Earhart-in-the-Marianas stories about which investigators from the mainland were starting to inquire. Patton interviewed a number of people on Saipan, including members of the family of Josephine Blanco Akiyama and people who had held positions of authority during the Japanese administration. He concluded that:

A preponderance of hearsay evidence, and the statements of people who were in the area in 1937, failed to indicate that Subject [sic: Earhart] crashlanded her airplane on Saipan, or that she was buried at Saipan. The hearsay evidence advanced by two informants set forth supra: Jesus Salas and Jose Villagomez, tended to indicate that the Japanese at Saipan had known at least the approximate location of Subject’s crash to have been in the Marshall Islands (Patton 1960:9).

In The Search for Amelia Earhart, published in 1966, Fred Goerner began with Josephine Blanco Akiyama’s story, but after years of study came to believe that Earhart had come down and been captured in the Marshalls. Navy veterans told him a story they had heard from a trusted Majuro schoolteacher named Elieu Jibambam, who had heard it from a Japanese friend named Ajima. Some time before the war, Jibambam said Ajima had told him, a white woman flier had run out of gas and landed between Jaluit and Ailinglapalap. Goerner concluded that she landed at nearby Mili Atoll. The story said a Japanese fishing boat picked her up and took her to Jaluit, whence she was taken to Kwajalein and then to Saipan. Mr. Jibambam apparently told this story as early as 1944 to U.S. Navy Lt. Eugene T. Bogan (No author 1944; Goerner 1966:163-5).

Goerner believed that Earhart was on an “unofficial” spy mission and had flown over Chuuk (then known as Truk) before heading toward Howland. He says that the Electra was fitted with extra-powerful engines that would permit her to travel this extra distance in the allotted time. He surmises that when she was unable to find Howland, she headed northwest hoping to reach the Gilberts, but ended up in the Marshalls where she ditched.

According to Joe Klaas, as set forth in his 1970 book Amelia Earhart Lives, the Electra was shot down by the Japanese at Orona (then called Hull Island) in the Phoenix group on July 2, 1937. Like Goerner, Klaas and his primary source, retired Air Force officer Joe Gervais, hypothesize that Earhart flew over Chuuk on a spy mission and then flew toward Howland. Klaas posits that they went to the Phoenix Islands looking for Kanton (then known as Canton Island) with its improved runway, where they could land safely and lie low while the Navy searched for them – at the same time checking out the Marshalls to see whether the Japanese were fortifying them. But the Japanese, he proposes, had an aircraft carrier in the Phoenix Islands, and shot the Electra down near Orona. They were captured at Orona and eventually taken to Saipan.

Klaas goes beyond Goerner in proposing that Earhart was flying a more advanced aircraft than the Electra. He suggests it could have been a secret copy of the new XC-35, which Lockheed flight-tested in May 1937. The XC-35 had a pressurized fuselage and would have been able to fly higher and faster than the Electra.

In 1985, Vincent Loomis published his version of Earhart’s capture at Mili Atoll: Amelia Earhart, The Final Story. His scenario is based on an analysis of her final flight by Paul Rafford, Jr. Rafford concluded that Earhart was blown off course toward the north during the night as she flew toward Howland Island after passing over Nauru. When she reached the 157-337 line of position she was well north of Howland, which she was unable to locate after searching along the line for about an hour. She then flew back toward the west expecting to find one of the Gilbert Islands, but she was farther north than she thought and her course took her to Mili Atoll in the Marshalls. She ditched the aircraft near one of the islands and was captured by the Japanese. They took her and Noonan to Saipan in a fishing boat.

The Loomis version differs from the others in that he does not hypothesize spying or secret aircraft modifications or substitutions. Rafford does posit that before departing Lae, Earhart changed her intended route of flight slightly to pass over Nauru, because Noonan allegedly had been drinking (Loomis 1985: 8) and could not be relied upon to navigate during the first portion of the flight (Loomis 1985: 97-99; 116). He speculates that Earhart was able to get to Nauru without Noonan’s help, and then flew toward Howland. By the time they were getting close to Howland and needed to know whether they had reached the 157-337 line of position, he has Noonan sober and able to do his job. He assumes they determined that they were on the line, but that unknown to them, the wind had blown them about 150 miles north of Howland. From there they flew westward and ended up at Mili Atoll when their fuel ran out.

Three years after Loomis published his account, T.C. “Buddy” Brennan III published Witness To The Execution: The Odyssey of Amelia Earhart. Brennan has Earhart and Noonan crashing and being captured at Mili Atoll and brought to Saipan, where late in the war Earhart, at least, was executed and buried.

Randall Brink also subscribed to the Mili Atoll story in his 1994 book, Lost Star, The Search for Amelia Earhart. Brink has Earhart on a spy mission for the U.S. government, flying a new aircraft with secret cameras. More powerful than the Electra, it was capable of flying from Lae to Chuuk and on to Howland. Even though the plane had advanced direction-finding capability, and thus should have been able to locate the Itasca, at some point Earhart turned back, wound up in the Marshalls and ditched at Mili. Earhart and Noonan were captured by the Japanese and put aboard the Japanese ship Kamoi. They were taken to Jaluit and then to Kwajalein. From there they were flown to Saipan. Brink contends they were held on Saipan for a time but were eventually imprisoned elsewhere. He does not believe the Japanese would have executed Earhart, but offers no conclusions about her ultimate fate.

In his 2002 With Our Own Eyes: Eyewitnesses to the Final Days of Amelia Earhart, Mike Campbell provides a fairly comprehensive summary of the Marshall Islands stories, but in the end expresses uncertainty in the face of his mentor Thomas Devine’s conviction that Earhart and Noonan flew directly to Saipan and landed there.

The possibility that Earhart was engaged in a mission to spy on Japanese activities in Chuuk is alluded to by several of the authors, though most make little of it. A “special section” of the online “CNMI Guide” (No author, n.d.) summarizes many of the eyewitness and other informant accounts discussed elsewhere in this paper, and implies that Earhart and Noonan might have been captured at Chuuk and transported to Saipan.

The Evidence

The evidence cited for the various versions of this story mostly comprises informant testimony, some by eyewitnesses, but much of it second- or thirdhand. In some cases, authors say that documentary evidence exists to support their assertions, but we have been unable to confirm the existence of such documents.

Patton’s information came from two informants on Saipan: Jesus Salas and Jose Villagomez. Patton said Salas told him that while imprisoned in Garapan he had overheard Japanese police talking about “a white woman’s airplane crashing at or near Jaluit Atoll” (Patton 1960:8). Sheriff Manuel Sablan told Patton that Villagomez had told him that he had overheard a similar conversation (Patton 1960:6).

Goerner collected a number of anecdotal accounts about white people in Japanese custody on Saipan before or during the war. He also spoke with a former Lockheed employee who told him he had helped modify the Electra to house secret cameras in the lower fuselage, and that more powerful engines and more fuel capacity were added. Goerner spoke directly with Elieu Jibambam, who said he had not seen the fliers himself but his good friend Ajima had seen them captured in the Marshalls. Goerner said that in 1964 he saw State Department files that convinced him the Electra’s engines were more powerful than the 550 horsepower Wasps with which it was originally equipped, and that Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz told him that Earhart had gone down in the Marshalls. In Washington he tried unsuccessfully to confirm some of Devine’s stories about seeing the Electra on Saipan. After his time in Washington, he and his colleagues sat down and reached a consensus regarding Earhart’s fate. Based on what they considered a preponderance of the evidence, they concluded that Earhart and Noonan were on a spying mission over Chuuk and had gone down in the Marshalls where they were captured.

It is difficult to determine why Klaas thinks Earhart was shot down near Orona. The island is close to the 157-337 line of position through Howland, but so are other islands in the Phoenix group. His book includes three frames from what he identifies as U.S. Navy 16mm footage taken near Orona in 1937, which he says show a Japanese flag flying over aircraft wreckage. His book also includes photos of the wreckage of a plane owned by Earhart’s friend and colleague Paul Mantz that crashed in Southern California; Klaas argues that this was Earhart’s original Electra – the one he proposes was secretly replaced with the XC-35.

Klaas cites the eyewitness testimony of various Saipan residents to establish Earhart’s and Noonan’s presence there. These sources are mainly those referenced by other researchers. However, he discounts reports that Earhart and Noonan were killed or died on Saipan.

The evidence in support of the Loomis hypothesis is largely different from the others. Loomis bases his assessment on the work of Rafford, a navigation expert who shows how the Electra could have been blown about 150 miles north of Howland, and from there could have flown westward to the Marshalls. Loomis cites the eyewitness testimony of Marshallese who said they saw the Electra ditch near one of the Mili Atoll islands. He also recounts a story told by Bilimon Amaran, who was a medical corpsman in the Japanese Navy before and during the war. Amaran said he treated an injured male flier aboard a Japanese cargo ship at Jaluit. He says there was a female with the man and the plane they had been flying, with one wing broken, was on the afterdeck of the ship. Amaran did not know what happened to the fliers after he saw them, but other witnesses cited by Loomis said they saw them on Saipan and thought that they had died there. To support his belief that Earhart considered Noonan an unreliable navigator on the Lae-to-Howland leg, Loomis relates Lae radio operator Harry Balfour’s reported recollections that Noonan “was on a bender” during the three-day layover in New Guinea, and “was put on board with a bad hangover ...” Loomis links this report with the fact that “(w)hen her husband’s last wire arrived at Lae, querying Amelia about the cause of the delay, she wired back a terse ‘Crew unfit.’” (Loomis 1994:8)

The evidence cited by Buddy Brennan in his 1988 book begins with his visit to the Marshall Islands in 1981. Brennan was a Houston businessman and veteran of Korea and World War II; he visited Majuro hoping to recover and restore old Japanese airplanes. There, he met a Mr. Tanaki, who told him that a friend who had worked on the crew of the Japanese patrol ship Koshu said the ship had been sent to find “the American airplane that crashed.” Brennan thought that the airplane must have been Earhart’s, and after some study he returned with a team to the Marshalls. On this visit, additional interviews led him to focus on a spot between Mili Atoll and Jaluit rather than on Majuro as the place where islanders first spotted the Electra. From there, his informants told him, the airplane’s crew were taken to Kwajalein, then Chuuk, Saipan, and, ultimately, mainland Japan. Brennan later discarded the notion that the captives were taken to Japan, instead concluding that they ended their days on Saipan.

Brennan cites much of the same eyewitness testimony reported by others, but also puts considerable weight on secondhand or generalizing statements by authoritative people in the Marshalls. His faith in these statements is apparently based on the conclusion that the individuals involved “couldn’t possibly have collaborated” with one another. Among others, Brennan quotes Oscar de Brum, then First Secretary to the President of the Republic of the Marshall Islands (RMI), as saying that “there’s no question they went down in the Marshalls” (Brennan 1988:76).

Randall Brink’s account of the Earhart disappearance is closest to that of Goerner. However he also says he had input from people associated with substituting a different aircraft for the Electra and installing advanced radio and direction finding capability. Brink quotes a number of post-loss radio receptions reported by amateur radio operator Walter McMenamy to suggest that Earhart broadcast for several days after landing in the Marshalls. McMenamy reported hearing Earhart broadcasting as she was captured by a Japanese officer of whom she said, “He must be at least an admiral” (Brink 1994:151). Brink presents a photograph taken over Taroa in the Marshalls in 1944 that he says shows the Earhart plane, missing one wing, sitting on a concrete revetment (Brink 1994: unnumbered page after page 160). He cites several of the witnesses quoted by other researchers who reported seeing Earhart and Noonan on Saipan but contends that none ever reported seeing them executed. He does not believe they died on Saipan but provides no evidence to support this conclusion.

Mike Campbell’s book provides a useful summary not only of the sources cited in other books, but of a number of less well-known stories as well. These include a 1989 verbatim transcript of Bilamon Amaron’s story, published in the February 1996 Amelia Earhart Society Newsletter by Joe Gervais and Bill and John Prymack, along with a number of more or less corroborative stories collected by Gervais, Prymack, Loomis, Joe Klaas and others, previously published in the Newsletter or in other on-line sources. He gives considerable attention to a 1993 letter from Fred Goerner to J. Gordon Vaeth, in which Goerner expressed reservations about Amaron’s account and raised concerns about how Marshallese and other Micronesian eyewitness stories may have been tainted by repeated questioning. Goerner’s letter also provides some background to Nimitz’s statement, which was apparently based on something the admiral was told by his close friend Capt. Bruce L. Canaga. Interestingly, according to Campbell, Goerner said Canaga had described an abortive 1938 plan by the Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) to use the excuse of seeking to determine Earhart’s fate as cover for an infiltration of the Marshalls (Campbell 2002:157).

The highly speculative “special section” of the online “CNMI Guide” (No author, n.d.) cites only one piece of actual evidence – the message received from Earhart by Lae at 07:18 GMT, when she reported she was some 740 nautical miles (roughly 850 statute miles) away; the unidentified author says this message should not have been audible at Lae, suggesting that Earhart was not where she said she was (and by implication, was en route to Chuuk).

|

| The Electra Was at Aslito Field

|

The Story and its Evolution

The story that Earhart’s Electra was at Aslito Field in 1944 was first propounded in 1987 by Thomas E. Devine in Eyewitness: The Amelia Earhart Incident. According to Devine, he came ashore on Saipan in July 1944 as the top NCO in the 244th Army Postal Unit and went with his commanding officer to Aslito Field shortly after their arrival. There, he said, they encountered a group of enlisted men, evidently on guard duty outside a hangar. Their commander seemed military but wore a white shirt open at the collar. Devine said he overheard conversation indicating that Amelia Earhart’s plane was inside the locked hangar. He said he asked one of the Marine guards if this was true and received confirmation that it was. Devine said he later realized that the man in the white shirt was Secretary of the Navy James V. Forrestal.

Devine recalled that later in the day he met one of the Marine guards, who said, “They’re bringing up Earhart’s plane” but then changed the subject. A few hours later, Devine said, he saw a civilian plane fly over, with two engines and double tail fins. Devine said he could clearly read the plane’s identification number: NR16020, which he did not at the time know to be the number on Earhart’s Electra.

After dark, Devine said, he and another member of his unit surreptitiously returned to Aslito, which he had been told was “off-limits.” Here he says he saw the plane that had flown over. He said they walked up to it, tried unsuccessfully to get inside, and again saw the NR16020 number on the tail. He said he saw about a dozen cans of fuel nearby.

After returning to his bivouac, Devine said he heard a muffled explosion at Aslito Field. Going to a vantage point, he said he could see a blazing fire; he concluded that the plane he had visited earlier was now aflame. Devine was convinced that the plane, although not destroyed, was burned to make it impossible to identify it as Earhart’s.

All this happened, Devine said, on his first day on Saipan in mid-July 1944. He kept the matter to himself until 1962, when he sought permission to visit Saipan and unearth Earhart’s and Noonan’s remains – whose location he thought he knew based on what he had been told by an Okinawan woman. In trying to convince the Navy that he had valuable information, he recounted what he said he had seen at Aslito Field, and later built Eyewitness based on this story and his pursuit of Earhart’s grave.

The Evidence

When Devine published his book in 1987, his version of events at Aslito was the only evidence that they had occurred. In Eyewitness, Devine closes with a plea for anyone to contact him who might be able to confirm what he reported, even if “you merely hold memories in the shadows” (Devine 1987:179). This appeal produced a number of responses, notably from Henry Duda. Duda had been on Saipan in 1944 as a PFC in the 2nd Marine Provisional Rocket Detachment and said he had seen a man who others identified as Forrestal (Campbell 2002:16). Duda became a vigorous supporter of Devine’s efforts to solicit more eyewitness accounts from former servicemen. Some two dozen accounts were published in 2002 by Mike Campbell (with Devine), in the book titled With Our Own Eyes. Some of these accounts related to Earhart’s and Noonan’s putative graves and other aspects of Devine’s overall story, but several men reported seeing a civilian airplane at Aslito or in the air. Some of the accounts are quite vivid and detailed, and some servicemen report recognizing or being told that the aircraft was Earhart’s.

|

| Earhart Was at the Garapan Prison |

The Story and its Evolution

However she got there, and whether or not the Electra was on Saipan, there are reports that Earhart was incarcerated in the prison at Garapan. In at least one story Noonan was there as well.

Goerner reported that Jesús Salas, a farmer on Saipan and presumably the Salas interviewed by Patton, was put in Garapan prison in 1937 and remained there until U.S. Marines released him in 1944. He told Goerner that a white woman was placed in a cell next to his for a few hours in 1937. He said his guards told him that she was a captured American pilot. Salas said he saw her only once, but his description was similar to those given by others on Saipan for the American woman. He recalled that after a time the woman was removed to a hotel in which the Japanese kept political prisoners.

Loomis spoke with Florence Kirby and Olympio Borja on Saipan in 1979. They told him that their grandfather had been imprisoned for three months in 1937 in a cell that was not far “from the one that was said to be occupied by the American woman pilot” (Loomis 1985:94). Loomis visited the ruins of the prison and saw the cell that tourists are told is the one in which Earhart was held. In 1981 Loomis returned to Saipan and spoke with Ron Diaz, then sixty-five years old. Diaz said he had seen “a white woman in the back of a truck with Japanese men with her” (Loomis 1985:110). He did not recall seeing a white man with her. He said he had been told by friends that the woman had been taken from the water, and that he was also told she had been taken to Garapan prison.

Loomis reports that Ana Villagomez Benavente of Saipan said that while visiting her brother at Garapan prison, she saw an American woman captive there. “She was an American ... I saw her at least three times” (Loomis 1985:132). Ms. Villagomez Benevente also said she washed clothes for the woman while she was housed at a hotel in Garapan City. In the apparently verbatim 1977 transcript of an interview with Ms. Villagomez Benavente by Fr. Arnold Bendowske, she reports washing clothes for the woman during her hotel residence, but refers to the jail only when rather aggressively led to do so by her interviewer (Bendowske 1977: 14-15).

The June 10, 1992 Bangor (Maine) Daily News published a story about former Navy nurse Mary Patterson, who was stationed on Saipan in 1946 and reported being told by an unidentified Chamorro informant of an American woman and man who were held and tortured at the Garapan prison (Curran 1992).

The Evidence

The evidence for Earhart’s presence at the Garapan prison comprises stories by first- and secondhand informants as discussed above, bolstered by one piece of semi-documentary data and one piece of “hard evidence.”

The semi-documentary evidence is discussed in print most recently by Mike Campbell, though it has been reported elsewhere. Campbell writes that in 1975 Thomas Devine received information from a Chicago-based Earhart researcher named William Gradt, who among other things provided “a copy of a photograph of etchings found on a wall inside a cell in the Garapan prison.” The illustration of these etchings in Campbell’s book is apparently a tracing; it shows what appear to be a conjoined “A” and “E” surrounded by obscure markings that look to the authors like eroded Japanese characters but have been interpreted by one of Campbell’s correspondents as symbols consistent with Earhart’s astrological chart and presumed situation (Campbell 2002:90-95). Campbell says that Devine saw the inscription but made nothing of it until contacted by Gradt. The senior author of this paper made a cursory search for it in 2004 but could not find it and was told that it had deteriorated.

The “hard” evidence is a small steel door, with “A. Earhart” and the date “July 19 1937” carved into it. According to Campbell (2002:98-102) as well as a letter Ms. Deanna Mick wrote to the National Air and Space Museum’s Thomas Crouch on April 4, 1994, and 2012 correspondence with the senior author, it was given to Ms. Mick by Saipan resident Ramon San Nicholas when Ms. Mick and her husband returned to the mainland after running a charter air service they had set up in 1978 on Saipan (c.f. Mick 1994; Campbell 2002:98-9). Devine apparently regarded the door as evidence that Earhart was imprisoned at Garapan, identifying it as having covered a small rectangular food service opening let into the barred front of a cell.

|

| Earhart Was Held Elsewhere on Saipan |

The Story and its Evolution

Various authors report that Saipan residents saw a white woman flier in Japanese custody before the war without specificity about where she was held. The recollections of several people, however, have her housed in the Kobayashi Royokan Hotel in Garapan City. In summary, the story is that sometime in 1937 a white man and woman were brought to the Japanese military police headquarters in Garapan for questioning. From there the woman was taken to the Garapan prison, while the man was taken to the Muchot Point military police barracks. After only a few hours at the prison, the woman was taken to the hotel, which had been taken over in 1934 by the Japanese to house political prisoners.

The Evidence

The evidence for the presence of Earhart at the hotel is anecdotal. Several witnesses have been quoted by multiple sources as outlined below:

Matilde (Fausto Arriola) Shoda San Nicolas lived with her parents in a home adjacent to the hotel in 1937 and 1938. She said she saw the white woman many times as she walked in the yard. She thought the woman had been at the hotel several months. Near the end of her stay the woman seemed to be ill and often visited the outhouse in the yard. Then Ms. San Nicolas saw the woman no more, and was told by a servant from the hotel that she had died of dysentery. Shortly before the woman died, she gave a gold ring with a white stone to Ms. San Nicolas’s sister but it was lost after the war. This version of the story with minor variations is reported by Goerner, Davidson, Klaas, Loomis and Devine. Several of the investigators spoke with Ms. San Nicolas personally, and Fr. Arnold Bendowske had a verbatim transcript made of his 1977 interview with her (identified as Matilde Fausto Arriola). When Goerner in 1961 showed her photos of fifteen different women clipped from magazines and newspapers, he reports that Ms. San Nicolas “unhesitatingly chose the likeness of Earhart. She reportedly said, ‘This is the woman; I’m sure of it, but she looked older and more tired’” (Goerner 1966:101).

José Pangelinan said he had seen the American man and woman on Saipan before the war. He said the man had been held at the military police stockade area while the woman was held at the hotel. He said that the woman had died of dysentery and the man had been executed the following day. He had not witnessed either death, but had been told by Japanese that the two had been buried together in an unmarked grave. Goerner interviewed Pangelinan; Klaas and Devine also relate his version of events.

Ana Villagomez Benavente earned money by doing laundry for the people held in the hotel. She said she saw the white woman “upstairs on the veranda” but was given the laundry by the “landlords.” After a time there was no more laundry from the woman, and Ms. Villagomez Benavente was told that she had been taken elsewhere. Both Loomis and Devine include versions of Ms. Benavente’s story in their books, and Fr. Bendowske’s transcripts include an interview with her.

Joaquina M. Cabrera also did laundry for the Japanese and the prisoners at the hotel. Her story as documented by Goerner: “One day when I came to work they were there ... a white lady and man. The police never left them. The lady wore a man’s clothes when she first came. I was given her clothes to clean. I remember pants and a jacket. It was leather or heavy cloth, so I did not wash it. I rubbed it clean. The man I saw only once. I did not wash his clothes. His head was hurt and covered with a bandage, and he sometimes needed help to move. The police took him to another place, and he did not come back. The lady was thin and very tired. Every day more Japanese came to talk with her. She never smiled to them but did to me. She did not speak our language, but I know she thanked me. She was a sweet, gentle lady. I think the police sometimes hurt her. She had bruises and one time her arm was hurt. She held it close to her side. Then, one day ... the police said she was dead with disease” (Goerner 1966:239). Klaas and Devine include references to Mrs. Cabrera’s story.

Antonio G. Cabrera lived on the main floor of the hotel in 1937. He reported seeing the white man and woman there, under surveillance by the Japanese. He said they were only there for about a week and were taken away. He recounted his story to Joe Gervais in 1960, as documented by Klaas.

|

| U.S. Military Personnel Found Physical Evidence of Earhart |

The Story and its Evolution

Several U.S. military personnel involved in the taking of Saipan and other Micronesian islands reported finding physical items whose existence was consistent with the belief that Earhart was captured by the Japanese on Saipan or at least held there.

Some Marines and GIs reported finding photographs of Americans, including Earhart, sometimes displayed on walls of buildings abandoned by the Japanese on Saipan and other islands; one described finding a map marked with her intended course of flight. Others described finding photos of Earhart on the bodies of dead or living Japanese soldiers. Robert Wallack, a Marine who took part in the invasion of Saipan, reported finding an attaché case in Garapan containing papers that appeared to him to be related to the world flight. Others reported finding a suitcase and an Earhart diary on Kwajalein, where some stories have Earhart being taken after she ditched in the Marshalls and before she was taken to Saipan.

The Evidence

Although the items described are tangible artifacts, almost none can now be found, so the available evidence for the “found objects” stories is largely anecdotal. Reports of such items are summarized below:

In 1960, Briand reports the “rumor” that “in July of 1944, during the invasion of Saipan ... the Marines found in an abandoned Japanese barracks a photograph album filled with snapshots of Amelia Earhart in her flying clothes. It is known that Earhart carried a camera with her on the world flight but not that she was carrying a photograph album filled with pictures of herself” (Briand 1960:191).

Goerner, in his 1966 book, reports that several GIs wrote to him after his trips to Saipan were publicized. Harry Weiser of New York was on Saipan during the invasion. He reported finding a small snapshot of Earhart tacked to one wall of a Japanese house. Weiser took the photo and some larger publicity prints of American actors. The photo of Amelia was published in the New York Daily News in November 1961. It turned out to have been taken in Honolulu in 1937 (Goerner 1966:169-70). Why it was found on the wall on Saipan is unknown.

Frederick Chapman of New York wrote to Goerner to say that he had seen snapshots of Earhart on Saipan during the invasion and thought that some of his buddies might still have some (Goerner 1966:172).

Ralph R. Kanna of New York was involved in interrogating prisoners during the Saipan invasion. He said that one prisoner had in his possession a photo, not a magazine clipping, which showed Earhart standing near Japanese aircraft on an airfield. Kanna said the photo was forwarded through channels to the Intelligence Officer. According to Kanna, the prisoner said that the woman in the picture had been captured along with a male companion and both had been executed (Goerner 1966:172).

Robert Kinley of Virginia wrote to Goerner that he had found a photograph of Earhart with a Japanese officer tacked on a wall on Saipan. He said he had lost the photo in July 1944 when he was wounded. He recalled that the photo showed Earhart standing in an open field with a Japanese soldier, and he thought that the latter was wearing some kind of combat or fatigue cap with a single star in its center (Goerner 1966:186-7).

W.B. Jackson of Pampa, Texas told Goerner that, “in February 1944, on the Island of Namur, Kwajalein Atoll, Marshall Islands, three Marines brought a suitcase from a barracks. They reported that the room they had found it in was fitted up for a woman, with a dresser in it. In the suitcase they found a woman’s clothing, a number of clippings of articles on Amelia Earhart, and a leather-backed, locked diary engraved 10-Year Diary of Amelia Earhart. They wanted to pry open the diary but when Jackson explained who Amelia was, how the government had searched for a trace of her, and that this should be taken to Intelligence, they closed the suitcase and started toward the Regimental Command Post with it. That is the last Jackson saw or heard of it” (Goerner 1966:277-8).

In 1994 Randall Brink published the account of Robert E Wallack of Connecticut who was a Marine on Saipan in 1944. In Garapan, Wallack said he entered what may have been a Japanese Government building. He found a locked safe, which he and others blew open with explosives. “After the smoke cleared,” he said, “I grabbed a brown leather attaché case, with a large handle and a flip lock. The contents were official looking papers, all concerning Amelia Earhart, maps, permits and reports apparently pertaining to her around-the-world flight. I wanted to retain this as a souvenir, but my Marine buddies insisted that it may be important and should be turned in. I went down the beach where I encountered a naval officer and told of my discovery. He gave me a receipt for the material, and stated that it would be returned to me if it were not important. I have never seen the material since” (Brink 1994:159). This account also appears in Campbell’s 2002 book and in a statement by Wallack in the Smithsonian Institution’s Veteran’s History Project (Wallack n.d.).

At least two reports documented in TIGHAR’s files do not appear to have been published elsewhere:

The New Hampshire Sunday News on July 14, 1991 reported that the discovery of an old newspaper clipping on Earhart’s disappearance had motivated 70-year-old ex-Marine Ivan George Gibbs to remember finding an area on Saipan – during the “mopping-up” phase of the 1944 invasion – that was littered with Japanese ledger books and human bones, including a small diary that Gibbs and another Marine concluded was Earhart’s. Gibbs said they gave it to a Marine colonel and never saw it again. The contents of the diary were not reported in the Sunday News (Hammond 1991).

In a letter to the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum’s Thomas Crouch dated March 20, 1992, Raymond Irwin, a veteran of the Saipan invasion, described finding a small dugout at Aslito containing a map he thought might be associated with Earhart (Irwin 1992). He included a photocopy of the map with his letter, which Dr. Crouch shared with TIGHAR. The map depicts the western Pacific and shows the boundaries of Japan’s League of Nations Mandate, labeled in Japanese. It is hand-marked with an "X" at the approximate location of Howland Island. A handwritten note by Mr. Irwin says that on the original, there is a mark “by the Japanese who put in the route track and Japanese writing in blue ink.” (Irwin 1992). The blue ink did not reproduce in the photocopy. Mr. Irwin also enclosed a photocopy of an armband marked with Japanese characters, and said he had also found flags and photographs.

|

| Earhart and Noonan Were Executed (or Died) and Were Buried on Saipan or Tinian |

The Story and its Evolution

There are several variations on the story that Earhart and Noonan died or were killed on Saipan (or Tinian) and were buried there. Briand says they were shot but does not indicate how or where they may have been buried. Brennan reports Earhart’s execution by firing squad. Others say that Earhart died of dysentery, that Noonan was beheaded, and that they were buried individually or in a common grave. Various locations of the putative gravesite have been identified by informants, and some of them have been excavated with both positive and negative results.

The Evidence

Briand reports that Josephine Blanco Akiyama told him she saw a man and a woman dressed like a man in Japanese custody at Tanapag Harbor. “The American woman who looked like a man and the tall man with her were led away by the Japanese soldiers. The fliers were taken to a clearing in the woods. Shots rang out. The soldiers returned alone.” (Briand 1960:194) There is no mention of burial.

During his first visit to Saipan in 1960, Goerner interviewed over 200 Saipanese; the testimony of thirteen of them could be “pieced together” to support Ms. Akiyama’s story. None of these accounts supported the Briand version that the white fliers had been shot. None of the Saipanese said they knew what had finally happened to the mysterious white people, but “several felt that either one or both of them had been executed.” (Goerner 1966: 49)

Prior to his second visit, Goerner heard from Thomas Devine, who related the story (later recounted in his own book) that he said he had heard regarding the grave of a white man and woman who “came from the sky a long time ago” and were killed by the Japanese (Goerner 1966:69). Devine supplied Goerner with photos from Saipan and detailed maps indicating the purported gravesite. Goerner’s attempts to follow Devine’s directions and to recover the remains during his second visit are described elsewhere in this paper. He located teeth and bone fragments which he sent to the U.S. for evaluation.

On his second trip Goerner also spoke with Matilde Shoda San Nicolas who related her story about the white woman who had been held in the hotel and had reportedly died of dysentery. He spoke with José Pangelinan, who said he had seen the man and woman, but not together. He also said that the woman had died of dysentery, but that the man had been executed. They were buried together, he said, in an unmarked grave outside the cemetery south of Garapan City. He had not witnessed any of this but had heard of the events from the Japanese military. He said that the exact gravesite was known only to the Japanese.

After his return to California, Goerner was contacted by Alex Rico, who told him of acting as an interpreter on Saipan while there as a Seabee in 1944 and 1945. He said that several Saipan residents told him that the Japanese had bragged about capturing “some white people” and bringing them to Saipan where they were buried “near a native cemetery.” He indicated that there were two native cemeteries; he was not sure which one was referred to.

On his third trip to Saipan Goerner spoke with several Saipanese, including some he had talked with before, who repeated vague stories they had heard from others that the two fliers had died or had been killed and buried somewhere near a cemetery in or near Garapan.

According to Davidson’s account, in 1967 Vincente Camacho showed Donald Kothera and his colleagues from Cleveland three photos said to depict the gravesite identified as Earhart’s. The investigators then spoke with Anna Magofna who related that while coming home from school one day when she was seven or eight she saw two white people digging outside a cemetery with two Japanese watching them. “When the grave was dug, the tall man with the big nose, as she described him, was blindfolded and made to kneel by the grave. His hands were tied behind him. One of the Japanese took a samurai sword and chopped his head off. The other one kicked him into the grave.” (Davidson 1969: 104) She did not mention the death of the woman, but she knew the location of the grave. She took them to the site when they returned to Saipan in 1968; they excavated and recovered burned and unburned human bones that they sent to the Ohio Historical Society for analysis.

Loomis repeats the story that the white woman being held at the Garapan hotel died of dysentery in mid-1938 as related to him by Matilde San Ramon.

Thomas Devine reports that in 1944 an Okinawan woman showed him the purported gravesite of the white man and woman who were killed by the Japanese several years before. The woman also said she knew where other Americans had been buried; a translator told Devine that she appeared to want favors from the Americans for providing this information (Devine 1987:63).

Despite the stories they had collected in the Marshalls about Earhart and Noonan being taken to Japan, in the second phase of his investigation Buddy Brennan and his team became convinced that Earhart had been executed on Saipan late in the war. According to Brennan, a Chamorro woman named Nieves Cabrera Blas said that she had personally witnessed Earhart’s execution by firing squad. She said Earhart had been blindfolded, but the blindfold was torn away as a gesture of respect before she was shot over an open grave and hastily buried. Blas showed Brennan the location,2 where his team then excavated with a backhoe and turned up a piece of cloth that Ms. Blas interpreted as the blindfold she had seen (Brennan 1988:146-7) According to Brennan’s associate Mike Harris (2002), the location was “obviously a dump area,” containing animal bones, medical ampules, and aircraft pieces.

One story suggests that Earhart and Noonan were buried on Tinian. Mr. St. John Naftel, of Montgomery, Alabama, was a Marine gunner on Tinian after it was taken from the Japanese in 1944. He reported being shown a set of graves where he was led to believe that Earhart and Noonan were buried after being executed. In 2003 he returned to the island accompanied by then-U.S. Navy archaeologist Jennings Bunn and relocated the site he had been shown. The site was then excavated by archaeologists under the direction of Michael Fleming and Hiro Kuroshina without finding evidence of graves (Bunn et al n.d., Frost 2004; King 2004).

In a 1999 letter to TIGHAR, Mrs. John Doyle recounted her husband’s story that in 1949, as a member of the 560th Composite Service Company, he visited a church on Saipan where a priest showed him an unmarked grave in a small cemetery that he said was where Earhart was buried. According to Mr. and Mrs. Doyle, the priest said Earhart had been buried there “to hide her body from the Japanese” (Doyle 1999).

In 1996, an article in the Pacific Daily News (Whaley 1996) reported the story of Ted Knuth, who said he had been an agent for the American Office of Strategic Services (OSS) on Saipan before and during the 1944 invasion. Knuth reportedly said that “he was sleeping under a tree when a Chamorro man jumped out and led him to an area behind enemy lines,” where he showed him the graves of two “white people” and “gave an exact description of Earhart and… Noonan” as well as of the Electra. Scott Russell, then with the CNMI Historic Preservation Office, was quoted in the same article, commenting that he and his colleagues had talked with Knuth and “(h)e told some fairly outlandish stories.” Some detail on Knuth’s story was recorded by William Stewart (1996; also see Stewart n.d.).

George Gibbs, in his 1991 recollections referred to above, reported that the area littered with ledger books where he and another Marine found a diary they thought was Earhart’s also contained the skeleton of a woman without a head (Hammond 1991).

In a letter to the editor of a newspaper in Tampa, Florida dated October(?)12, 1991,3 Edward Lauden, an Army combat photographer on Saipan in 1944, says he was directed to photograph a small clearing just north of Garapan that contained several Japanese grave markers. He reports that his film was then taken from him by officers, whereupon the markers were removed, the area doused with gasoline and burned and then bulldozed. An officer then cautioned him to forget what he had seen, and when he asked what it was all about, the officer whispered “Amelia Earhart” (Lauden 1991).

In summary, the evidence for Earhart and/or Noonan dying and/or being buried in the Marianas consists of a number of eyewitness and secondhand accounts, together with a piece of cloth interpreted as a blindfold and two collections of human bones. The accounts variously have the woman identified as Earhart dying of dysentery and being executed by firing squad, while the man identified as Noonan is executed either by firing squad or beheading.

|

| A U.S. Government Cover-Up |

The Story and its Evolution

Visiting Saipan in 1960 to investigate the stories of Josephine Blanco Akiyama and others, Fred Goerner found himself confronted with official denials and non-cooperation, and suspected that the government knew more than its representatives were willing to acknowledge. He outlined some suspicions, in relatively measured fashion, in his 1966 book.

Randall Brink, who posited that they were on a secret spying mission with a newly designed, government-provided airplane, asserted that the government holds extensive files on what really happened to Earhart and Noonan that remain secret to this day. Other researchers make similar claims.

Joe Klaas and Joe Gervais offer a complex version of the cover-up hypothesis, in which Earhart and Noonan were engaged in a spy mission and survived the war, returning to the U.S. under government protection. They propose that Earhart took on the identity of Irene Bolam, while Noonan ended his days in a mental hospital in New Jersey.

Klaas and Gervais did not initially suspect a government cover-up, but say that the State Department was concerned in 1960 about the effect their interviews might have on U.S.–Japanese relations (Klaas, 1970:92). Then they say they learned that the Defense Department had a classified file on Amelia Earhart and heard from a friend at the Pentagon that Ambassador Douglas MacArthur and officials at the State Department were “all worked up” about their investigations (Klaas 1970:103-104). Their suspicions were heightened, they say, when a member of the USS Colorado’s crew who participated in the Earhart search declined to answer a question about searching in areas unreported by the press at the time, claiming that the information was classified (Klaas 1970:114).

Klaas and Gervais concluded that if Earhart had been captured by the Japanese, both the Japanese and U.S. governments would have kept the matter hidden – the Japanese fearing reprisal for a military buildup forbidden by their League of Nations mandate, and the U.S. being unwilling and unable in 1937 to fight a war with Japan. (Klaas 1970:136).

Klaas and Gervais went on to postulate that much of the U.S. Navy’s search for Earhart was in fact a cover for collecting information on Japanese military buildups in the Mandate, that the Japanese, having captured Earhart, tried to use her as a pawn in blackmailing the U.S. during World War II, and that the U.S. refused the Japanese gambit and abandoned Earhart to her fate.

But Earhart, they say, survived her captivity because of her political value as a bargaining chip and was ultimately rescued by her friend and colleague Jackie Cochran at the close of the war (Klaas 1970:231). It was in exchange for Earhart, they say, that Emperor Hirohito was allowed to remain on the throne (Klaas 1970:230-231). They go on to propose that successive U.S. presidents up to the time of their book’s publication had maintained the cover-up for reasons of political expediency.

Vincent Loomis did not believe in a government cover-up, but one of his sources, navigator Paul Rafford, hints at a conspiracy in his own 2006 book, Amelia Earhart’s Radio: Why She Disappeared. Rafford reports that Firman Gray, an engineer on Earhart’s aircraft, was quoted in a 1992 book (Kennedy 1992) as saying that he took two R1340 engines to Indonesia and installed them on the Electra. “If it happened,” Rafford wrote, “it was pre-planned by someone. If so, by whom?” (Rafford 2006:61-63). He also reports that Mark Walker, a Pan American copilot flying out of Oakland at the time of Earhart’s world flight, said he heard Earhart say, “This flight isn’t my idea. Someone high up in the government asked me to do it” (Rafford 2006: 25).

Rafford comments that whether or not Earhart was spying, her disappearance in the Pacific “would have given our Navy an excellent chance to update its mid-Pacific charts in time for World War II.” He speculates that Earhart and Noonan could have secretly landed on Kanton Island where he assumes people were stationed to take care of them until the Navy, having completed its survey, “was ready to find them” (Rafford 2006:117). He expresses the suspicion that Earhart’s failure to communicate with the Itasca during the last leg of her flight may have been intentional; there were, he says, so many missed opportunities for two-way communication as to suggest that the communications failures were willful, not accidental (Rafford 2006:116). As another indicator of a government plot, he quotes Secretary of the Treasury Morgenthau as saying after Earhart’s disappearance that she “absolutely disregarded all orders” (Rafford 2006:117).

Thomas Devine provides what may be the most dramatic expression of the cover-up hypothesis, asserting that he saw the Electra destroyed at Aslito by American forces at the direction of Secretary of the Navy Forrestal, and that the government has taken many steps since 1944 to assure that what happened will never be known. He and Mike Campbell, in Campbell’s 2002 book, describe in some detail the roadblocks that Devine believes the government has thrown in the way of his investigation. He raises the possibility that Forrestal’s untimely death and the seeming disappearance of some eyewitnesses are related to the cover-up, and posits President Roosevelt’s personal involvement in the conspiracy. Devine, Campbell and others say or imply that the seeming disappearance of the briefcase said to have been found by Robert Wallack and the Earhart-related photographs and documents reportedly found by other U.S. military personnel is further evidence for such a conspiracy.

The reason for the cover-up, according to most proponents of the idea, is that Earhart was engaged in a spy mission and the U.S. did not and still does not want this fact to be disclosed. Devine and Campbell posit a somewhat more elaborate geopolitical rationale, proposing that the U.S. government, and notably Secretary Forrestal, were intent on forging a U.S.-Japan alliance against the Soviet Union after World War II and wanted to avoid the public outcry against Japan that would be occasioned by the revelation that the Japanese had captured and murdered Earhart.

The Evidence

The available evidence for the cover-up hypothesis is derived from eyewitness accounts and stories of non-cooperation, obfuscation, and suspicious-seeming behavior by government agencies. Devine in particular describes a number of activities by government and ex-government personnel that – if they occurred as he describes them – would raise almost anyone’s suspicions.

For instance, Devine says that shortly after receiving his orders to return to the U.S. from Saipan in 1945, he was approached by a man he took to be from the Navy, who told him he was to return by air rather than by ship with the rest of his unit. The “Navy man” told him to abandon his barracks bags, as he would not be needing them. An argument ensued, during which the Navy man said: “They’re waiting for you. You know about Amelia Earhart.” Eventually Devine, the Navy man, and Devine’s bags were driven to the harbor, where the Navy man told Devine to get aboard a PBY4 for the flight to Hawaii. Devine refused to board without orders, whereupon “my escort turned and started running up a nearby hill. I looked at the seaplane and the unfriendly, silent man on the dock – apparently the pilot – and muttered, ‘The hell with this,’ and I quickly dragged my barracks bags to the road and hitched a ride back to the replacement depot’” (Devine 1987:64-6; Devine in Campbell 2002:75). Devine returned to the mainland by sea with his unit, and apparently suffered no ill consequences, but he recounts a number of other strange encounters with government officials, suddenly silent eyewitnesses, and interactions with possible intelligence personnel in the course of his later investigations.

|

| Critique |

The Five Pieces of “Hard” Evidence

There are five pieces of “hard” physical evidence that have been or could be taken to support the Earhart-in-the-Marianas hypothesis in varying degrees: Deanna Mick’s door, Buddy Brennan’s blindfold, several airplane parts, two collections of human bones, and Raymond Irwin’s map.

The Door

The small steel door with the words “A. Earhart” and the date ”July 19 1937” inscribed on it was reportedly given to Ms. Deanna Mick by the late Ramon San Nicholas when Ms. Mick and her late husband left Saipan (Mick 1994; Campbell 2002:98-9). At our request and working from a full-scale tracing that Ms. Mick included in her 1994 letter to Dr. Tom Crouch of the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum, Scott Russell of the CNMI Humanities Council made a cardboard template of the door and tried to match it to the apparent food service hatches on the surviving cells in the Garapan jail. He found that the door perfectly matched the openings in all six northernmost cells in the sixteen-cell main cellblock, so it appears to be a legitimate artifact of the Japanese jail (Russell 2012). In 2012 email correspondence with the senior author, Ms. Mick reported that the hinges appeared to be snapped off, not cut with a hacksaw (Mick 2012). This suggests that the door was broken off the cell front after it became rusted to the point at which it would no longer swing on its hinges. Only then would moving it back and forth snap it off.

We see two reasons for thinking that the door was not inscribed by Amelia Earhart, or any inmate at the jail.

- The inscription would apparently have been on the inside of the door, consistent with being made by an inmate, but every time the door was opened, the inscription would have been displayed to those outside. Thus it could not have been made in secret, so if it was made by an inmate, it must have been with the acquiescence of the jailers. This may be what happened, but it seems implausible.

- The inscription is not just scratched; it is rather deeply cut into the metal. This suggests use of tools that it seems unlikely an inmate would possess.

According to Ms. Mick, Mr. San Nicholas presented the door to her because she was the second female pilot to fly through the Marianas – Earhart ostensibly being the first. We think that on balance it is most likely that Mr. San Nicholas removed the door from the jail and made the inscription as a gently joking way of honoring Ms. Mick.

The Blindfold

Buddy Brennan and his colleagues found what he and his informant, Ms. Nieves Cabrera Blas, interpreted as Earhart’s blindfold about 7.5 feet deep at the site where Ms. Blas said she had seen a woman Brennan presumed to be Earhart executed and buried. They reported finding no human bones; Brennan speculated that soil chemical and microbial conditions were such that the woman’s bones had not been preserved while the “blindfold” had (Brennan 1988:146-7; Sallee 1986).

The cloth may represent a blindfold, but it also could represent many other things. Before the 1944 invasion, Garapan was a substantial town whose residents wore clothes and used cloth for other purposes. The town was massively bombarded in 1944, creating many opportunities for pieces of cloth (among other things) to collect in holes and get buried. Mike Harris, who says he worked with Brennan, describes the location as a dump area (Harris 2002). Brennan’s excavation apparently was not conducted using archaeological methods, and he presents no record of the stratigraphic position in which the cloth was found. If the cloth was indeed associated with a human body buried at the site, one would expect at least some bones to have survived (to say nothing of the deceased’s clothes). Soil conditions on the west side of Saipan are actually fairly conducive to the preservation of bones; burials have been recovered in the area from as early as the Pre-Latte period, two to four thousand years ago. The only reason to think that the cloth might be a blindfold appears to be that according to Brennan, Ms. Blas identified it as such.

Airplane Parts

When he visited Saipan in 1960, Fred Goerner pulled a generator and other aircraft parts from Tanapag Harbor and took them to California. The generator closely resembled one that had been installed on the Electra. It was disassembled and found to match the Electra’s Bendix model “perfectly in every respect” according to Paul Mantz, who had installed the generator on Earhart’s plane (Goerner 1966:65). However, when Goerner sent the generator to Bendix for evaluation, the company’s specialists found sufficient discrepancies in its details to satisfy them that it had not been manufactured by Bendix. They identified it as a Japanese generator apparently copying a Bendix design (Goerner 1966:67).

In 1968 Don Kothera and his colleagues visited Saipan to search for the fuselage of a civilian aircraft Kothera recalled seeing there as an 18-year-old Navy man in 1946. After several days of hacking through the jungle in the area where he recalled seeing the plane, and getting help from a local resident who knew the island well, they found the location where Kothera thought the fuselage had been twenty-two years earlier. They located “six screw type aircraft tie-downs” and some plane parts. They picked up some of the airplane parts with numbers stamped on them.

Back on the mainland, Kothera’s group found that the numbers on the parts they had collected could not be tied to any specific aircraft. Chemical analysis by Crobaugh Laboratories of Cleveland, Ohio indicated four percent copper in the alloy, and Alcoa Aluminum Co. advised that neither the Germans nor Japanese used copper in their aluminum alloys; they used the more readily available tin. The conclusion was that the aluminum airplane parts had been made by Alcoa prior to 1937 (Davidson 1969:118).

Although the parts may well be of American origin, this does not mean they were from Earhart’s Electra. By the time Kothera saw the fuselage in 1946, Saipan had been in American hands for two years; a great many American aircraft had been on and over the island. It is possible to imagine that Kothera’s fuselage represented the Electra hidden away after the plane landed on or was brought to the island, but it could also have been the discarded carcass of an American military plane.

Bones

On his second trip to Saipan in 1961, Fred Goerner attempted to locate the gravesite described to him by Thomas Devine. Based on photos provided by Devine, Goerner found what he believed to be the cemetery Devine had described near the purported gravesite, but noted that some of the directions provided by Devine were incompatible with the cemetery’s actual layout. Doing the best he could with the directions, Goerner selected a fifteen by fifteen foot plot and began digging there. He and his workers went down nearly five feet and found nothing. Next he selected a location a little farther west; that site yielded nothing but an unexploded hand grenade, which was carefully disposed of. The third try was a few yards closer to the graveyard. They found bones about two and a half feet down. Screening the soil from the hole, they found a total of seven pounds of bones and thirty-seven teeth, which they thought represented two individuals, a man and a woman (Goerner 1966: 107-11).

Goerner obtained permission from Muriel Morrissey (Earhart’s sister) and Mary Bea Ireland (Noonan’s widow) to have the bones and teeth analyzed. They were delivered for evaluation to Dr. Theodore D. McCown, a well-qualified physical anthropologist at the University of California, Berkeley. McCown concluded that the bone fragments and teeth were from four or more individuals, and probably represented the “secondary interment of the fragments of several individuals.” The hypothesis that these were the remains of Earhart and Noonan was thus not supported (Goerner 1966: 177-84).

In 1967, Don Kothera and his group recovered almost 200 bone fragments, most of them cremated, from the site adjacent to the cemetery shown them by Anna Magofna. The bones, together with a dental bridge and an amalgam gold tooth filling, were analyzed by Martha Potter and Dr. Raymond Baby (pron. “Bahbee”) of the Ohio Historical Society, who concluded that the roughly 188 cremated bone fragments, representing an ulna, a fibula, one or more femurs, ribs, vertebrae, and bones of the hands and feet, “are those of a female, probably white individual between the anatomical ages of 40-42 years,” with “an age of 40 years” being “probably more correct.” They identified the single unburned bone, part of the frontal bone of the cranium, as representing “a second individual, a male” (Baby and Potter 1968). Upon Baby’s death in the late 1970s, the bones were apparently lost (Kothera & Matonis[?] n.d.), and their whereabouts remain unknown (Potter-Otto 2012; Snyder 2012).

The lee side of Saipan, where all the excavations for Earhart’s and Noonan’s bones have taken place, was densely occupied in pre-contact times (c.f. Russell 1998; Butler & DeFant 1991), and human burials are commonly found in pre-contact archaeological sites on the island. Considering the disturbance of such sites during the Japanese development of the island, and the presence of 20th century cemeteries that then experienced considerable bombardment and other disturbances during the 1944 invasion, the presence of human bones almost anywhere is no surprise. In addition, both sets of bones are reported to have been found in the vicinity of historic cemeteries and, in the case of Kothera’s bones, a crematorium (Kothera & Matonis[?] n.d.), which had also presumably experienced disruption by the 1944 bombardment. Potter’s and Baby’s identification of the cremated remains as those of a “white” female is intriguing, but it should be recalled that Saipan had a substantial European population during the German period (1899-1914; see Russell 1984; Spennemann 1999); it is unclear whether the crematorium that may have produced the bones now lost in Ohio pre-dated the Japanese period. Even if it did not, the presence of osteologically European people on Saipan during the Japanese period would not be entirely surprising; besides traders passing through and missionaries remaining from the German period, there had been genetic mixing between Europeans and Micronesians since at least the mid-nineteenth century, producing a mixed-race population that survived into and through the Japanese period.

In summary, the bones recovered by Goerner were identified as those of several disarticulated individuals, none of whom it seems reasonable to think was Earhart or Noonan, while those recovered by Kothera’s team could be those of Earhart and Noonan but could also quite plausibly be those of other people. The gold bridge and filling found by Kothera’s group could have belonged to Earhart or Noonan or to any number of Micronesian, German, Spanish or Japanese residents of Saipan; without relevant dental records it would be impossible to link them to specific individuals even if they could now be found.

The Map

As discussed above, Raymond Irwin’s 1992 letter to Thomas Crouch included a photocopy of a map he said he had found in a dugout at Aslito Field in 1944. The original of the map may be in the possession of Mr. Irwin’s family; Mr. Irwin passed away in 2010. The original map was apparently marked with blue ink, which did not reproduce in the photocopy; according to Mr. Irwin, the markings indicated the location of Howland Island and a “route track,” presumably Earhart’s. All we can tell by looking at the photocopy is that it does depict the Japanese mandate, and that the labels for island groups are in Japanese. Also enclosed in Mr. Irwin’s letter was a photo of a Japanese military arm band, and he reported seeing Japanese flags and photos. If marked as Mr. Irwin reported, the map would suggest that someone in a military capacity at Aslito was interested enough in Howland Island and Earhart’s route to mark them on a map. This is not surprising; the Japanese were certainly aware of Earhart’s flight, and reportedly searched for her. The map is thin evidence of her presence in the Marianas, however.

Credibility of Flying to Saipan from Lae

Four authors argue that Earhart piloted the Electra to Saipan. None asserts that she was on a spying mission and purposely flew into Japanese-controlled territory. Three (Briand 1960, Devine 1987, Campbell 2002) speculate that various problems led to huge navigation errors, and she flew to Saipan without really knowing where she was. Davidson simply accepts that she flew to Saipan without trying to explain how it happened. Campbell accepts that Earhart and her Electra could have reached Saipan in other ways, but his primary source, Devine, is sure that Earhart piloted her plane to the island.

To accept the “flew to Saipan” premise, one has to explain how this could have happened given that Saipan is almost due north of Earhart’s takeoff point at Lae and she was trying to fly east to Howland Island.

Earhart departed Lae at 10:00 in the morning local time (00:00 Greenwich Mean Time [GMT]5). As she flew eastward toward Howland in daylight, she should have been able to see where she was for the first several hours using maps at her disposal, and she successfully radioed position reports to Lae indicating that she was on course for Howland Island. Her last report received by Lae indicated that she was near the Nukumanu Islands, about 900 miles east of Lae, after flying for a little over seven hours. Up to that point, just as night came upon them, things seemed to be going well. What could have happened next to make them fly northwest from their last reported position, winding up at Saipan?

Briand suggests that something completely disorienting happened after this last radio report. He speculates that the Electra’s compasses “tumbled” during the night and that Noonan’s chronometers lost their calibration. He proposes that Noonan was unable to get any fixes during the night, so they were flying blind. By the time the sun came up in the east as they were flying northwest, they had to know they were completely lost. When they finally saw land, after some 26 hours of flight, their fuel ran out and they ditched in the harbor at Tanapag. Briand acknowledges that the Itasca heard transmissions from the Earhart plane early that morning. He does not account for the fact that there was nothing in her messages to suggest the problems that he attributes to the flight – that in fact the messages indicated that she thought she was on track and close to Howland.

Devine suggests that the “hair-raising” takeoff from Lae may have adversely “affected the compass and delicate robot pilot, causing the Electra to stray from its intended course.” He suggests that Noonan may have injured his head during the takeoff and that Earhart would have used the error-prone Sperry Robot Pilot to control the plane while she crawled to the rear of the plane to attend to Noonan’s injuries. But if this had happened, would Earhart not have simply returned to Lae, to fly another day? Devine would have us believe that she flew on, making periodic radio reports to Lae that everything was going well.

Devine cites other factors that could have helped to disorient the flight crew – radio problems, the need to avoid rain squalls about 250 miles east of Lae, and the need to pump fuel manually each hour from the auxiliary tanks to the wing tanks, during which time the plane was presumably controlled by the auto-pilot.

All these factors may have been in play, but the fact remains that Earhart reported good progress as of the time of the last transmission received by Lae, when the position she reported indicated that they should have been about 900 miles to the east. None of the radio messages to Lae indicate that Noonan was injured on takeoff, and the content of two messages, saying that “everything (is) OK” seems inconsistent with the notion that Noonan was disabled.

Another consideration that undermines the “Earhart flew to Saipan” premise is that receipt of radio transmissions was documented by the Itasca as the Electra should have been approaching Howland Island. All of the authors (Briand 1960, Davidson 1969, Devine 1987, Campbell 2002) acknowledge and discuss these receptions to some extent. Table 1 below presents the documented receptions at Lae by Harry Balfour and at Howland Island by Leo Bellarts and other radio operators aboard the Itasca. The “S-N” code represents the reported strength of the signal, with S-1 being very faint and S-5 being loud and clear.

|

Date/Time |

Where Received |

Frequency |

Message |

7/2, 04:18 GMT

(14:18 at Lae) |

Lae (Balfour) |

6210 kHz |

Height 7000 feet, speed 140 knots … everything OK |

7/2, 05:19 GMT

(15:19 at Lae) |

Lae (Balfour) |

6210 kHz |

Height 10000 feet position 150.7 E 7.3 S cumulus clouds everything OK |

7/2, 07:18 GMT

(17:18 at Lae) |

Lae (Balfour) |

6210 kHz |

Position 4.33 S 159.7E height 8000 feet over cumulus clouds wind 23 knots |

7/2, 14:15 GMT

(02:45 on Itasca) |

Itasca |

3105 kHz |

Bellarts reported "Heard Earhart plane but unreadable thru static" |

7/2, 15:15 GMT

(03:45 on Itasca) |

Itasca |

3105 kHz |

Stronger reception: Will listen on hour and half on 3105 (very faint, S-1) |

7/2, 16:23 GMT

(04:53 on Itasca) |

Itasca |

3105 kHz |

Bellarts reported "Heard Earhart (part cldy)" |

7/2, 17:44 GMT

(06:14 on Itasca) |

Itasca |

3105 kHz |

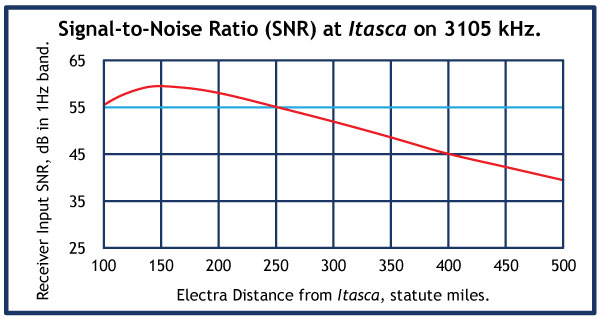

Bellarts: "Wants bearing on 3105 // on hour //will whistle in mic." About 200 miles out. (S-3) |

7/2, 18:11 GMT

(06:41 on Itasca) |

Itasca |

3105 kHz |