Frequency, wavelength, and antenna tuning

Much of the discussion of the technical difficulties that Earhart and Noonan faced on the final flight involves consideration of frequencies and wavelengths used and the corresponding antennas and equipment used to generate or receive the various frequencies/wavelengths. The technical evaluation of the likelihood of whether a radio in Miami could have received transmissions from an aircraft stranded in the Western Pacific also uses this fundamental terminology. If you want to follow those arguments, you must familiarize yourself with these terms.

Frequency and wavelength

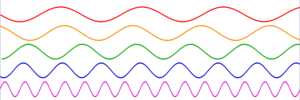

There is an inverse relationship between frequency and wavelength: the lower the frequency, the longer the wavelength; the higher the frequency, the shorter the wavelength.

The frequency of a wave is measured in cycles per second. Many of the historical records use "kcs" as an abbreviation for "kilocycles per second"--where "kilocycles" is "1000 cycle." At present, we use "Herz" to stand for "cycles per second."

Abbreviations

1 cycle per second = 1 Herz = 1 Hz

1,000 cycles per second = 1 kiloHerz = 1 kHz

1,000,000 cycles per second = 1000 kHz = 1 MegaHerz = 1 MHz

1,000,000,000 cycles per second = 1000 MHz = 1 GigaHerz = 1 GHz

Examples

7500 kcs = 7500 kHz = 7.5 MHz

2.4 GHz = 2.4 GigaHerz = 2.4 billion cycles per second (some cell phones and similar appliances)

Optimizing an antenna

Radio waves are transmitted from the movement of an electromagnetic wave along a conductor--the antenna wire. If we had unlimited resources, it would be best to have an antenna that was at least one wavelength long. This is not too difficult with high frequences (short wavelengths--or "short waves"). Popular HAM radio equipment operates on wavelengths of 2 meters, 6 meters, and 40 meters; it is not too hard to rig full-wave antennas for these wavelengths. A full-wave 2.4 GHz antenna is only 4.92" long.

If one cannot afford the space for a full-wave antenna, the next best thing is to use an antenna that is a half-, quarter-, eighth-, or sixteenth-wavelength.

Tuning coils can compensate to some extent for antennas that are not an even fraction or multiple of a wavelength.

Earhart's frequencies and antennas

As a general rule, TIGHAR prefers to use the metric system. In this table, the units are given in feet to match the units used in the sources.

| Frequency | Full wavelength | 1/4 wavelength | Optimum antenna | Actual antenna |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 500 kHz | 1968' | 492' | 246' | |

| 3105 kHz | 316.9' | 79.2' | ||

| 6210 kHz | 158.4' | 39.6' | ||

| 7500 kHz | 131.2' | 32.8' |

Notice that Earhart's daytime frequency (6210 kHz) is double her nighttime frequency (3105 kHz). The wavelength is halved as the frequency is doubled. This means that one antenna could serve both frequencies fairly well. A quarter-wave antenna for 6110 kHz would act as a one-eighth-wave antenna for 3105 kHz.

The reason for having a daytime frequency different from the nighttime frequency is that the ionosphere affects radio wave propagation. An old rule of thumb is "The higher the sun, the higher the frequency."