- Welcome to TIGHAR.

Recent posts

#1

Radio Reflections / Re: Something does not add up

Last post by Martin X. Moleski, SJ - February 15, 2026, 01:06:35 AMThe loop antenna was a receiving antenna.

The loop was more directional than a straight-wire antenna.

Here are directions about how to build your own "resonant magnetic loop" to do DF.

Handheld Finding Loop Antenna for RFI Location

The fact that the only time they received any signals was when they kicked in the loop antenna bolsters the theory that something was wrong with the ventral (belly) antenna.

One receiver. Two antennas.

The loop was more directional than a straight-wire antenna.

Here are directions about how to build your own "resonant magnetic loop" to do DF.

Handheld Finding Loop Antenna for RFI Location

The fact that the only time they received any signals was when they kicked in the loop antenna bolsters the theory that something was wrong with the ventral (belly) antenna.

One receiver. Two antennas.

#2

Radio Reflections / Re: Something does not add up

Last post by Colin Taylor - February 12, 2026, 06:44:33 AMThe question remains, how did Earhart receive the 7500kcs signal if the ventral receiver aerial was damaged? The fact that she reported hearing the 7500kcs morse code signal debunks the broken aerial theory. But why was she unable to tune 3105 or 6210? If there was only a single receiver with a static aerial and a loop aerial, that does not explain how she could tune one HF frequency and not another.

Elgen Long, in his book, is quite clear that Radioman Joseph Gurr briefed Earhart on the Bendix RA 1 receiver and direction finder before her departure from California on the second attempt. In Long's book there is a photo attributed to PAA mechanic F Ralph Sias in Miami about May 26 showing the cockpit with the RA1 above the window. Therefore there were two receivers in the Electra but only one ventral static aerial.

Elgen Long, in his book, is quite clear that Radioman Joseph Gurr briefed Earhart on the Bendix RA 1 receiver and direction finder before her departure from California on the second attempt. In Long's book there is a photo attributed to PAA mechanic F Ralph Sias in Miami about May 26 showing the cockpit with the RA1 above the window. Therefore there were two receivers in the Electra but only one ventral static aerial.

#3

General discussion / Re: Update from AE's House

Last post by Diego Vásquez - February 07, 2026, 03:32:02 PMMy pleasure Marty. Nice to hear from you.

#4

Radio Reflections / Re: Something does not add up

Last post by Martin X. Moleski, SJ - February 04, 2026, 07:52:30 AMQuote from: Colin Taylor on February 02, 2026, 09:26:26 AMAfter the crash and rebuild there was only one ventral aerial.It has been years since this was an active topic here.

Was that aerial connected only to the Western Electric receiver?

In which case if the Bendix RA 1 receiver was not connected to the static aerial, she could not tune the Bendix receiver to 7500, only to 1500 through the loop antenna.

Or was the single aerial connected to both the WE and the Bendix receivers?

Can two receivers be simultaneously connected to a single aerial? (I don't think so, both receivers would need to be tuned simultaneously to the same frequency).

Or is a switch needed to flip the aerial from one receiver to the other?

Or is one receiver switched off when the other is in use?

I have three summary articles dating from back then.

Radio equipment on NR16020

NR16020 antennas

Loop antenna

The transmissions were on the V-antenna. The transmitter was crystal-controlled, so AE could only transmit on three pre-tuned frequencies. She had "three-channel Western Electric equipment of the type then being used by the airlines to provide one channel at 500 kc and the other two at [3105 and 6210 kHz]."

The Western Electric Model 20B receiver could scan frequencies on four bands. A band was selected and the frequency adjusted by hand.

Excerpt from the article on radio equipment aboard the Electra:

QuoteRic Gillespie: "I think there was a Bendix device aboard the aircraft that allowed the loop to be used with the Western Electric 20B receiver. I think it was integral to the Bendix MN-5 loop and was the same device described on page 42 of the August 1937 issue of Aero Digest magazine. Under the heading "Aero Radio Digest - The Newest Developments in the Field of Aircraft Radio" the first article is entitled "Bendix D-Fs". I quote: 'Bendix D-Fs are designed to operate in conjunction with Bendix Type RA-1 receiver, but will also give accurate and dependable bearings when used with any standard radio receiver covering the desired frequency range.'"[8]I think you have confused the limited range of frequencies that the Bendix could use for DF with a limited band of frequencies that could be received. The Bendix just fed what was received to AE's headset as she rotated the circular directional antenna on top of the fuselage. That antenna was probably tuned for the local frequencies in its design. High Frequency Direction Finding (huff-duff) was only in its infancy in 1937. The Bendix was from an earlier era.

Ric Gillespie, Finding Amelia, p. 64.

Just what range of frequencies the Electra's homing device could cover is an important question but not a difficult one to answer. A hoop-shaped "loop" antenna mounted above the Electra's cockpit received the signals for direction finding. Numerous photos taken from the time of its installation just prior to Earhart's first world flight attempt in March until the final takeoff from Lae, New Guinea, in July leave no doubt that the loop antenna on Earhart's Electra was one of a new line of Bendix direction finders pictured and described in the August 1937 issue of Aero Digest magazine: "Bendix D-Fs are designed to operate in conjunction with Bendix Type RA-1 receiver, but will also give accurate and dependable bearings when used with any standard radio receiver covering the desired frequency range." The article also notes that these receivers can be used "as navigational direction finding instruments within frequency range of 200–1500 kilocycles."[9] Those parameters generally agree with the limits described by Manning and Miller prior to the first world flight attempt ("Plane has direction finder covering 200 to 1430 kcs").[10] They also agree with Putnam's message of June 25, 1937, saying that the plane's direction finder "covers range of about 200 to 1400 kilocycles."[11] Where Earhart got the idea that her direction finder could cover "from 200 to 1500 and 2400 to 4800 kilocycles" is not clear, but the signals she requested on 7500 kilocycles were far beyond even those limits.[12]

Hooven was extremely unhappy that AE removed his system and regressed to the Bendix loop: "Before Miss Earhart took off on her Round-the-World flight she removed from her plane a modern radio compass that had been installed and replaced it with an older, lighter-weight model of much less capability. I am the engineer who had invented and developed the radio compass that was removed, and I discussed its features with Miss Earhart before the installation was made. I have reason to believe that it was the failure of her radio direction-finder to do what the more modern model could have done that caused her to be lost. The story is told herein, and it is plain to see why I have been so very much interested in the subject."

One More Good Flight, Ric Gillespie, 2024 (p. 139):

"Earhart ... turned on the Bendix direction finder and tuned her Western Electric receiver from 3105 kcs to 7500 kcs, heard the dit-dah, dit-dah, dit-dah through the static. Reaching above her head, she rotated the loop, trying to discern any change in the volume. If she could find the spot where the As were least audible, a needle on the instrument in front of her would give her the bearing to where the signals were coming from, but, try as she might, there was no change. Disappointing, frustrating, but hardly surprising: she had never been able to get the damn thing to work."

I think this answers your questions.

- Was that aerial connected only to the Western Electric receiver?

Yes. - Or was the single aerial connected to both the WE and the Bendix receivers?

There was only one receiver on board. - Can two receivers be simultaneously connected to a single aerial? (I don't think so, both receivers would need to be tuned simultaneously to the same frequency).

I don't know. Not applicable to this situation. - Or is a switch needed to flip the aerial from one receiver to the other?

A switch was used to connect the single receiver to one aerial or the other. - Or is one receiver switched off when the other is in use?

There was only one receiver.

It is tragic that the thought never crossed their minds that changing antennas suddenly allowed them to hear transmissions from the ground. The fact that the Itasca was transmitting As as they requested meant that the Itasca could hear them. They seem not to have tried just tuning the receiver back to the voice frequency that they had told the Itasca to use in order to test whether they could use the loop antenna to communicate. Or they could have played twenty questions, with the Itasca sending yes or no answers via Morse code.

I don't blame them. I often make mistakes in thinking things through. They were exhausted, they were deafened by the prop tips breaking the sound barrier a few inches away, they must have been at least somewhat anxious as one thing after another failed them. Hindsight is twenty-twenty vision, and we don't know what hindsight taught them in the last days of their lives.

So sad!

#5

Radio Reflections / Something does not add up

Last post by Colin Taylor - February 02, 2026, 09:26:26 AMIt is widely accepted that the Electra's ventral receiver aerial was damaged on take off at Lae. However, at 0758 Itasca local time Earhart reported she was circling and asked Itasca to transmit on 7500 kcs. She then said that she received the signal but cannot get a minimum. The DF loop control box could not be tuned above 1500kcs so how was she able to receive the 7500 signal if the ventral receiver aerial had been damaged at take-off at Lae? And if she could receive on 7500 why could she not receive signals on 3105 or 6210?

The attached pictures show the Electra before the crash at Hawaii (short V aerial attached to the dorsal mast at mid-cabin) and after the rebuild (dorsal mast at the front of the cabin). Before the crash there were two ventral receiver aerials supported by six masts (plus the trailing aerial mast) but after the crash and rebuild there was only one ventral aerial with three masts.

Previously when the Hooven automatic direction finder was fitted, it needed both a rotating loop aerial AND a static aerial to resolve the bidirectional ambiguity of the loop aerial. Hence there were two ventral receiver aerials, one connected to the Western Electric receiver and the other to the DF receiver. Before the crash at Hawaii, when the Bendix RA1 receiver and the manual direction finder was fitted there were still two ventral aerials so presumably the RA1 was connected to one of them in which case the RA1 could be tuned to 7500 as a receiver or to 1500 as a direction finder.

(It was not essential to connect the RA1 to the static aerial as the directional ambiguity could be resolved by the human operator but the RA1 would then be limited to the frequencies to which the loop aerial could be tuned).

After the crash and rebuild there was only one ventral aerial. Was that aerial connected only to the Western Electric receiver? In which case if the Bendix RA 1 receiver was not connected to the static aerial, she could not tune the Bendix receiver to 7500, only to 1500 through the loop antenna.

Or was the single aerial connected to both the WE and the Bendix receivers? Can two receivers be simultaneously connected to a single aerial? (I don't think so, both receivers would need to be tuned simoultaneously to the same frequency). Or is a switch needed to flip the aerial from one receiver to the other? Or is one receiver switched off when the other is in use?

Something does not add up. What do you guys think?

#6

Artifact Analysis / Re: Speculation on artifact 2-...

Last post by Martin X. Moleski, SJ - January 24, 2026, 09:21:23 AMThat's a blast from the past!

https://tighar.org/Projects/Earhart/Archives/Expeditions/NikuVI/Niku6dailiesweek2.html

Dateline: Nikumaroro, 0530 Local Time, 3 June 2010.

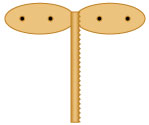

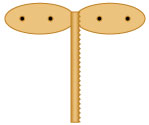

"Another thing was found, and right now they are thinking that it may be part of a vacuum tube used for target practice by the Coasties. They're calling it the "dragonfly." I have sketched it based on Ric's description, which is a risky thing to do, but I did it anyway. In total it measures about one inch by one inch, and is made of brass or copper. The center portion is a rod, too thick to be called a wire. It has serrations on one side – not threads, but regular indentations. The "wings" are flat and thin, with holes as shown. An interesting piece."

https://tighar.org/Projects/Earhart/Archives/Expeditions/NikuVI/Niku6dailiesweek2.html

Dateline: Nikumaroro, 0530 Local Time, 3 June 2010.

"Another thing was found, and right now they are thinking that it may be part of a vacuum tube used for target practice by the Coasties. They're calling it the "dragonfly." I have sketched it based on Ric's description, which is a risky thing to do, but I did it anyway. In total it measures about one inch by one inch, and is made of brass or copper. The center portion is a rod, too thick to be called a wire. It has serrations on one side – not threads, but regular indentations. The "wings" are flat and thin, with holes as shown. An interesting piece."

#7

Artifact Analysis / Speculation on artifact 2-9-S-...

Last post by James Champion - January 24, 2026, 07:57:57 AMThis item has always intrigued me. I believe I have an idea what it might be - the governor from a music box.

I am going by memory of what the item looks like as I can't find the particular TIGHAR Tracks that had a sketch.

If this is correct then the two holes on the 'wings' would have secured small pieces of flat steel by means of small tubular rivets. The length/area of these flat pieces would have been ground in length/size to set the tempo of the music. At one end would have been gear teeth to connect it to a larger gear on the. If these teeth are oriented in the axial direction, then this would have been the governor of a small spring-wound music box with low torque. If the teeth are helical, winding around the shaft, then this would have been the governor of something with higher torque like a weight-driven cuckoo clock. The mating gear in a high-torque mechanism would have been at a right-angle to the axis of the governor. Wind-up record players used a completely different governor mechanism. Given the environment any ferrous parts would have rusted away.

Did Amelia's cosmetic case have a music box in the lid?

Is it part of a timer from some other device?

Otherwise, I would say it is a spinner from a fishing lure. Maybe a re-purposed available music box item.

I am going by memory of what the item looks like as I can't find the particular TIGHAR Tracks that had a sketch.

If this is correct then the two holes on the 'wings' would have secured small pieces of flat steel by means of small tubular rivets. The length/area of these flat pieces would have been ground in length/size to set the tempo of the music. At one end would have been gear teeth to connect it to a larger gear on the. If these teeth are oriented in the axial direction, then this would have been the governor of a small spring-wound music box with low torque. If the teeth are helical, winding around the shaft, then this would have been the governor of something with higher torque like a weight-driven cuckoo clock. The mating gear in a high-torque mechanism would have been at a right-angle to the axis of the governor. Wind-up record players used a completely different governor mechanism. Given the environment any ferrous parts would have rusted away.

Did Amelia's cosmetic case have a music box in the lid?

Is it part of a timer from some other device?

Otherwise, I would say it is a spinner from a fishing lure. Maybe a re-purposed available music box item.

#8

General discussion / Re: Update from AE's House

Last post by Martin X. Moleski, SJ - January 21, 2026, 03:22:18 AMThanks for the virtual tour and the photos, Diego.

Very much appreciated!

Very much appreciated!

#9

General discussion / Update from AE's House

Last post by Diego Vásquez - January 15, 2026, 07:03:32 PMI live in the Pasadena area of Greater LA and happened to be passing within a few blocks of AE's old house on Valley Spring Lane in Tolucca Lake yesterday, so stopped by to see how it looked (I've stopped by once in a while before, but it's been at least ten years or so). Toluca Lake is a toney, subdued, and kind of quirky enclave in Los Angeles. Lots of stars have lived there over the years, Bob Hope is probably the best known long-time resident, but there were many more old timers who lived there for a time - Bing Crosby, Frank Sinatra, Andy Griffith, Roy Disney – and still many today, including Hillary Duff, Steve Carell, Andy Garcia, Ray Romano, Denzel Washington and more. It's not as gauche and grandiose as the Bel Air, Hollywood Hills, or Beverly Hill, but it's a centrally located place close to the studios for stars and execs who want to avoid all that glitz and glamour and just live pretty normally.

AE's house is pretty normal looking, large by most standards (5265 sq. ft), but just average for the area. Zillow lists it at $4.6 mil, also probably about average for the area. It's at the dead end of Valley Spring Lane, and her back yard abuts the beautiful Lakeside Golf Club (very swanky, I've been there a few times for events, not a member 😐). AE's house looks the same as the first time I saw it about 25 years ago or so, and probably hasn't changed much since she lived there. It's not marked in any way, except the house number, 10042. It's most distinctive feature is a cylindrical front corner that has some intricate glass and iron work (see photo). Do I remember something about George Putnam holding a séance in this front room after AE disappeared? Anyway, I took some photos of AE's house, in case anyone is interested. Then I went up and rang AE's doorbell, but she wasn't in.

Btw, across the street from her is the eponymous, tiny Toluca Lake, which is ringed in by houses that offer virtually no view of the lake from the street or any public viewing area, but the place across the street from AE's has been torn down for new construction, which gave me a chance to actually see the lake, so I took a photo of that too. I spoke briefly to the construction guys, who only spoke Spanish (common in LA), and explained to them about AE – they listened politely and nodded but had no idea of who AE was and didn't seem too interested.

Coincidentally, about 10-15 years I had some brief business interaction with a relatively quiet and discreet multi-billionaire (not Tim) who lives across the street and about two houses down from AE's place. In small talk with him back then, I found out that he was on the National Geographic board and had some moderate interest in AE. Small world.

AE's house is pretty normal looking, large by most standards (5265 sq. ft), but just average for the area. Zillow lists it at $4.6 mil, also probably about average for the area. It's at the dead end of Valley Spring Lane, and her back yard abuts the beautiful Lakeside Golf Club (very swanky, I've been there a few times for events, not a member 😐). AE's house looks the same as the first time I saw it about 25 years ago or so, and probably hasn't changed much since she lived there. It's not marked in any way, except the house number, 10042. It's most distinctive feature is a cylindrical front corner that has some intricate glass and iron work (see photo). Do I remember something about George Putnam holding a séance in this front room after AE disappeared? Anyway, I took some photos of AE's house, in case anyone is interested. Then I went up and rang AE's doorbell, but she wasn't in.

Btw, across the street from her is the eponymous, tiny Toluca Lake, which is ringed in by houses that offer virtually no view of the lake from the street or any public viewing area, but the place across the street from AE's has been torn down for new construction, which gave me a chance to actually see the lake, so I took a photo of that too. I spoke briefly to the construction guys, who only spoke Spanish (common in LA), and explained to them about AE – they listened politely and nodded but had no idea of who AE was and didn't seem too interested.

Coincidentally, about 10-15 years I had some brief business interaction with a relatively quiet and discreet multi-billionaire (not Tim) who lives across the street and about two houses down from AE's place. In small talk with him back then, I found out that he was on the National Geographic board and had some moderate interest in AE. Small world.

#10

General discussion / Re: New AI video on Youtube

Last post by Denise Kelsey - January 03, 2026, 05:58:07 PMGlad to see that it's been taken down and the user account discontinued.