|

August 1, 2000

The Last Expansion of the British Empire

One thinks of British imperial expansion as a thing of the 18th and 19th centuries. By the early twentieth century the British Empire had achieved a sort of stasis, in uneasy balance with the colonial enterprises of the other great powers. Its days of expansion were over, and with the end of World War II of course, it began to dismantle itself, morphing into today’s Commonwealth.

On the eve of the War, however, there was one last push into new territory – technically the expansion of an existing colony rather than the establishment of a new one, but so like a new colony that it can justly be called the last expansion of the Empire. This last hurrah, effectively lost to history in the tumult of world war, is worth reclaiming as a small but poignant part of British history, and as a memorial to a dedicated colonial officer who died in its service.

The colonial enterprise was the Phoenix Islands Settlement Scheme (PISS), and its martyr was Gerald B. Gallagher, whose grave monument stands today in the coconut jungle of an uninhabited South Pacific island, Nikumaroro.

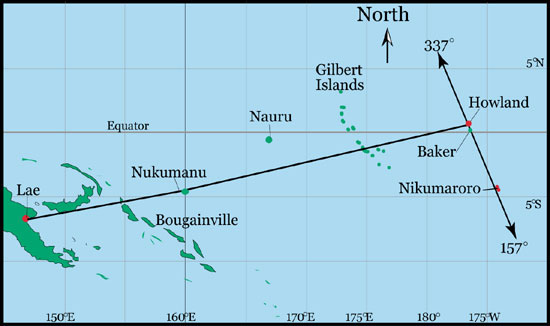

It is on Nikumaroro that my colleagues and I in The International Group for Historic Aircraft Recovery (TIGHAR) have crossed paths with Gallagher and the PISS. TIGHAR is engaged in a perhaps Quixotic quest for the long-lost American flyer Amelia Earhart, who disappeared en route to Howland Island, about 400 miles north of Nikumaroro, in 1937. For various reasons explained elsewhere, we think it likely that she wound up on Nikumaroro, dying there not too long before the island was reconnoitered for settlement as part of the PISS.1 Gallagher, it turns out, was involved in the discovery of a human skeleton on the island in 1940, which may well have been Earhart’s. As a result, we have learned a good deal about the man, and about the colonization effort he led. Our sources have included the archives of the Western Pacific High Commission, in the Foreign and Commonwealth Records Section at Hanslope Park, England, the Barr Smith Library at the University of Adelaide, Australia, interviews and correspondence with people who knew Gallagher, notably Mr. Harry Maude in Australia, Mr. Foua Tofinga in Fiji, and Sir Ian Thomson in Scotland, and our own archeological fieldwork and observations on Nikumaroro. The more we have learned, the more respectful we have become, and the more convinced that Gallagher’s story needs to be told regardless of its association with Earhart.

The Genesis of the P.I.S.S.

Blessed or cursed with a memorable acronym, the Phoenix Islands Settlement Scheme was the brainchild of the thoroughly remarkable Harry E. Maude, at this writing still alive and at work in Australia at 95. Mr. Maude and his wife Honor are among the most respected members of the Pacific historical community, but Maude was not always a historian. In 1937, he was a colonial administrator on the staff of the Western Pacific High Commission, which oversaw the Colony of the Gilbert and Ellice Island, the Solomon Islands, and other British colonies, protectorates, and interests in the western Pacific. The WPHC had its headquarters in Suva, Fiji, where its head, the High Commissioner, also served as Governor. Mr. Maude was assigned to the Gilberts and Ellices and here he became acutely aware of the plight of the southern Gilbertese.

On an island, the balance of population and resources is always a matter of great concern; an island can support only so many people. In pre-colonial times in the southern Gilberts, population size was kept in check in three major ways. One method was abortion, another disease, and the third warfare leading to emigration. The coming of European missionaries and colonizers, of course, put a stop to abortion and warfare (more or less), and exacerbated the situation by lengthening lives through modern medicine. By the time Harry and Honor Maude arrived in the southern Gilberts, the imbalance between people and land – which translates into food – was getting critical.

So Maude proposed the PISS, a program to colonize several of the uninhabited Phoenix Islands with land-poor families from the southern Gilberts and a few of the Ellice Islands that were in similar straits. Each colonized island, it was hoped, would in time become economically self-sufficient through the then-profitable trade in copra (dried coconut meat).

The Phoenix Islands are a group of eight islands plus reefs and shoals, scattered over about a quarter-million square miles of the Central Pacific Ocean. Today they are part of Kiribati (pronounced “Kiribas”), formerly the “Gilbert Islands” half of the Colony of the Gilbert and Ellice Islands. The people of Kiribati – “Gilbertese” in colonial days – are now referred to as I Kiribati (pronounced “E Kiribas”). In 1937 when Mr. Maude conceived the PISS, they were substantially uninhabited (as they are today), but there was evidence that some had significant populations in prehistory, and several reportedly had sufficient land, water, and resources to make them habitable. Maude consulted with islanders in the Southern Gilberts and on a couple of land-poor islands in the Ellices (now Tuvalu), and found enthusiastic support for a colonizing experiment in the Phoenix Islands.

In preparing the PISS proposal, Harry Maude naturally had to visit the islands he proposed to colonize. A reconnaissance was approved by government, and in October of 1937 Maude, cadet officer Eric Bevington, and nineteen I Kiribati delegates visited the Phoenix group. They arrived at their first stop, Gardner Island, on the 13th and spent the following two days looking it over.

“I shall always remember that first night in the Phoenix Islands,” Maude wrote. “We lay in a circle under the shade of the giant buka trees by the lagoon, ringed by fires as a protection against the giant robber crabs, who stalked about us in the half-light or hung to the branches staring balefully at us. Birds were everywhere and for the most part quite tame .… Unfortunately for them, both the crabs and birds were very good eating, and we gorged ourselves on a diet of crabs, boobies and fish.”2, 3

The largest of the Phoenix Islands was Canton (now Kanton). During World War II it would become the site of both British and American airbases. In the 1930s the U.K. and U.S. were in heavy competition for Canton as a possible flying boat base for transpacific commerce, and in 1937 nearly fell into a naval engagement over it. Between its uncertain political fate, and its lack of coconut trees, it was not a very attractive venue for settlement, and it was never colonized as part of the P.I.S.S.. Several other islands, such as McKean, Birnie, and Phoenix Islands, were too small and resource-poor to be considered for colonization. Three islands were given serious attention by the reconnaissance party: Sydney, Hull, and Gardner. The I Kiribati delegates were especially enthusiastic about Gardner; they associated it with Nei Manganibuka, a legendary ancestress who had come to the Kiribati home islands from a land with many buka trees that lay somewhere in the direction of Samoa. That island was called Nikumaroro in the legends, and thus Gardner Island became Nikumaroro. Sydney became Manra after a legendary ancestral place, and Hull became Orona, a Polynesian name borrowed from Niue Islanders who had worked coconut plantations there years before.4

On 2nd November 1938, the PISS was approved by High Commissioner Sir Arthur Richards, who requested that Maude accelerate implementation. Maude set to work with energy, and by early December had purchased supplies, arranged for shipping, settled legal affairs, and was off to collect the first group of settlers. Enthusiasm for the scheme continued to run high in the southern Gilberts:

No difficulty is being experienced in obtaining settlers, even at a few hours notice, and care is being taken to choose only those so notoriously poor that they would inevitably be included in any list based on relative poverty.5

Manra (Sydney) and Orona (Hull) both had substantial stands of producing coconut trees, but water resources on Orona were uncertain. Nikumaroro (Gardner) had only 111 coconut trees, the remains of plantings started there in the 1890s by John Arundel, a notable Pacific entrepreneur, but allowed to go fallow when Arundel’s attentions turned to phosphates early in the new century. So the initial plan of occupation called for a small group of settlers to be placed on Orona while the bulk of the party was settled on Manra. Nikumaroro would not initially be settled by potential colonists. Instead a ten-man working party was placed there to find water, establish a village, clear native vegetation, and plant coconuts.6

Settling the islands was not just a matter of moving people there and leaving them to their devices. The islands had to be made habitable not only by locating and developing sources of water but by constructing houses and other facilities. Coconuts had to be planted and tended, and before that could happen the indigenous vegetation had to be cleared and burned. Copra drying sheds had to be built on islands with bearing trees. The land had to be divided equitably among the settlers, who themselves had to be organized, or encouraged to organize themselves, into functioning communities – no mean feat considering that they represented unrelated families from several different islands. Governmental institutions had to be established, and that required the construction of administrative centers, dispensaries, and jails. Economic institutions like cooperative stories had to be organized, stocked, and subsidized for the interim until the settlements became self-sufficient.

The first few months were tough and chancy, particularly on Nikumaroro where water was found to be very scarce. Descendants of the first Nikumaroro settlers – who live today in a village called Nikumaroro in the Solomon Islands – still sing of the “great search for water” that preoccupied their ancestors. But eventually ground water was found, wells were dug and cisterns constructed, trees were planted, and the colony – on all three islands – looked to become a going concern. Some of the Nikumaroro working party members went home while others remained and were joined by their families. Orona proved to have sufficient water and its settlement grew, while two villages were established on Manra and work began on marking out land parcels for assignment to permanent settler families.

Harry Maude bore the official title Officer in Charge, Phoenix Islands Settlement Scheme. His job involved shuttling back and forth between the Phoenix settlements and the southern Gilberts, organizing immigration parties, arranging transport, getting supplies and seed coconuts, supervising transportation, and handling a myriad of administrative details. On-site in the Phoenix Islands, leadership fell to his assistant, a cadet officer named Gerald Gallagher.

Gerald Bernard Gallagher

Born July 6th, 1912, Gerald was the son of Gerald Hugh Gallagher, a doctor in the West African Medical Service, and Edith Gallagher. He attended Stonyhurst College, Cambridge University (Downing College, where he rowed crew), and St. Bartholomew's Hospital Medical School before joining the Colonial Administrative Service in 1936. At the time of his application for appointment in the Service, he was “studying agriculture on farm with Mr. G. Butler, Maiden Hall, Bennets Bridge, Co. Kilkenny, Ireland.”7

Photo courtesy Deirdre Clancy.

Gallagher was posted as a Cadet Administrative Officer to the Gilbert and Ellice Islands Colony on 30th September 1936, subject to the completion of training at Cambridge. On 5th July 1937 the High Commissioner, WPHC was notified that Gallagher had been “finally selected for probationary appointment” and would be en route to the islands shortly. Gilbert and Ellice Islands Colony Resident Commissioner J.C. Barley advised London of his arrival at Ocean Island on 21st September. He received his official appointment as Deputy Commissioner from High Commissioner Sir Arthur Richards on 3rd June 1938.

Gallagher had some difficulty learning the I Kiribati language. He “sat for examination” in March of 1937, and “failed to obtain the requisite percentage of marks.” However, the Examination Board concluded that “a few months in a district will enable him to pass in all subjects without any difficulty.”8 He was assigned to Funafuti and began to learn Tuvaluan, but was “strongly advised” by other officers to learn I Kiribati, which was regarded as “incomparably more useful as a general rule to officers in this colony.”9 He was popular in Tuvalu, however, and when he was taken to Suva in July of 1938 for the treatment of severe tropical ulcers he had developed, the people of Funafuti asked that he should remain.10 By September, however, with his ulcers presumably gone, he had been assigned to the PISS as Harry Maude’s second-in-command.11 In December he sailed with Maude and the first group of colonists to the Phoenix Islands, where he remained to supervise development while Maude returned to the southern Gilberts to handle the “home” end of the operation. Late in 1939 Maude became ill and could not continue in his oversight role; he was subsequently reassigned to Pitcairn Island. With his departure, effective 13th July 1940, Gallagher was appointed Officer in Charge, PISS.12

Getting the Colony on its Feet

Together with the bulk of the first settlers, Gallagher established himself on Manra. Here and elsewhere he had the assistance of Jack Kimo Petro (sometimes called Kimo Jack Pedro), a half-Tuvaluan/half Portuguese engineer and artisan of considerable skill and energy. On each island, too, his oversight was shared with an island magistrate and other government officials selected from amongst the colonists. With greater or less individual enthusiasm, all set about making the Phoenix Islands their home. Gallagher’s quarterly progress reports, filed with the Resident Commissioner of the Gilbert and Ellice Islands Colony, recount their accomplishments, setbacks, and adventures:

There has been considerable activity in the Phoenix Islands during the quarter ended the 31st March, 1940. Three hundred and eighty three persons have now been landed on the three islands of Gardner, Hull, and Sydney and, of these, three hundred and fifty four are permanent settlers. The settlement of one island, Sydney, is now completed and, with the arrival of some twenty more families, Hull Island will have reached the same happy state. About one hundred relatives of present settlers have also to be transported from the Gilbert Islands.13

Manra (Sydney) Island: Work during the quarter has been principally confined to the all important, if a little monotonous duty of setting out land holdings and endeavoring to ensure that each native gets a suitable allotment of land. Unfortunately, the non-delivery of certain surveying equipment ordered nearly eleven months ago will necessitate nearly all of this being done again .... Since many measurements, as at present recorded, have had to be made with a length of one inch rope and a two foot carpenter's rule.14

Steps are being taken to endeavor to counteract what appears to be a very heavy infant mortality rate.... Four months ago, this appeared to be well over fifty percent and it was reported that this was very largely due to incorrect care of the infants by their mothers. Women on each island were therefore encouraged to meet together and form "Women's Committees" with a view towards helping one another in baby welfare. One hundred copies of a book written by Mrs. G. H. Eastman of the London Missionary Society were purchased and distributed....15

Another task which has been accomplished, certainly the most difficult and, in many ways the most important task yet undertaken, has been the allocation, by the council of old men, of sitting places in the new Maneaba. The battle over this raged for several days and it appeared as if actual bloodshed was only avoided by dint of a decision that nobody should occupy the seat in the Maneaba which they were wont to occupy in the Mother islands.16

The Maneaba is the traditional meeting house in an I Kiribati village. It is where all important decisions are taken by the village elders, after a discussion that is highly structured with reference to the boti (“boach”), or seating position, of each family head. As Gallagher recognized, nothing was more important to the stability of the community than to solve the problem of who would occupy which boti. Since the colonists were drawn from different islands, there were overlapping rights to particular boti, and there no traditional models upon which to resolve the matter.

According to Kenneth Knudson of the University of Oregon, who studied the Manra community in the 1960s, Gallagher gave himself too little credit for settling the question of boti rights:

Gallagher finally settled the dispute by suggesting that the traditional boti system be abandoned. Instead each household was to be given its own place to sit, with no one being allowed in the place he had been accustomed to in the Gilberts. This was accepted. .... In honor of Gallagher, the maneaba was named "tabuki ni Karaka" or "Gallagher's accomplishment."17

Before he turned over the reins of command to Gallagher, Harry Maude made an extended visit to the settlements, and on Manra

I was very pleased indeed by the way in which the little community on Sydney had developed, led by the enthusiasm of Gallagher. .... Where before we had to cut our way through thick brush, two prosperous villages 18 were now situated, with neat and attractive homes fronting both sides of the broad road. To the south of the villages had been built a large school, where the children received daily instruction from a full-time master; to the north lay the island government station, with its offices, storehouses, homes for the resident officials, and two small gaols, which happily still remained untenanted. Close to the government station was the hospital with its Native Dresser, facing the sea, and the new transit quarters for the visiting European officers. In the centre was a large cistern, which provided water for the hospital and an emergency supply for the whole island in the unlikely event of the well water supplies failing. All around were evidences of peaceful progress ... and ... general contented well being ....19

By 5th July 1940, when Gallagher composed his progress report for April–June, he was ebullient about the settlement scheme's prospects:

There have been no very startling developments and yet, on the other hand, the usual disappointments and set Back.ks have not been experienced. Perhaps this latter phenomenon is only the corollary of the former and the present calm us but the overture to yet another local storm. Fair weather or foul, however, the settlement scheme has now set a steady course for the calm waters of success and prosperity which can be seen to lie ahead. If the sails continue to be filled with the sweet breath of goodwill, hard work and determined effort, it will now take much more than a few local set Back.ks to wreck a venture so well begun.20

In late 1940, with some 672 settlers in residence on Manra and Orona, with villages and government stations in place, the institutions of governance established, and coconuts being cut and processed into copra, it was Nikumaroro’s turn. A large contiguous tract on the southwest (lee) side of the island had been cleared and planted, a 20,000 gallon cistern was in place, wells were producing water, and all was in readiness for Nikumaroro not only to join the Phoenix colony, but to become its focal point. Gallagher had chosen it to be the government centre, and in late September he personally relocated there from Manra.

The Model Island of the Phoenix

On Nikumaroro Gallagher set out to create, in the words of High Commissioner Sir Harry Luke, “the model island of the Phoenix.”21 As on Manra, there were obstacles to be overcome – especially as wartime needs cut more and more deeply into available shipping and supplies. But Gallagher and his I Kiribati colleagues soldiered on, as documented in his progress reports, in the accounts of others, and in the archaeological evidence that TIGHAR’s work on Nikumaroro has found.

During the quarter, work was commenced on the construction of the skeleton of the Government Station .... Work was also commenced on the rather formidable task of clearing away the rocks and tree roots which have to be removed before the Station site can be leveled ... [and] on construction of the Rest House which, it is hoped, will be completed before the end of November.22

To complete this settlement, it is now necessary to arrange for the transport of some eighty new settlers and their families, as well as about ten thousand cubic feet of cargo ... but the vessel was unable to obtain the necessary supplies of fuel oil and had to lie idle at her home port.23

The second half of the quarter was marked by severe and almost continuous North-westerly gales, which did considerable damage to houses, coconut trees, and newly planted lands. Portions of the low-lying areas of Hull and Gardner Islands were also flooded by high spring tides, Back.ked by the gales, and, it is feared that many young trees have been killed.24

A new flagstaff, 69 feet high, was completed and erected ... and a section of the old temporary flagstaff was very suitably incorporated in the little church which the more devout or, at all events, less indolent, labourers were then erecting in their spare time.25

Unfortunately, very soon after the last house had been erected, the wind swung round to the North-west and it was soon obvious that the wet season had begun. With very little protection from the newly planted coconut trees and bereft of the windbreak formerly afforded by the "buka" trees, the gales managed to play havoc with the village in the first few days.26

Work on Gardner Island has been directed mainly towards the completion of the clearing and levelling of the Government Station area, the construction of roads and paths and the erection of a properly constructed latrine wharf to replace the sundry temporary structures swept away by the December gales .... Work was also commenced on the demarcation and plotting of landholdings on the South-west side of the island and some twenty of these lands have been taken over by labourers who intend to remain on the island as settlers.27

At right is a map of Nikumaroro showing the location of the colonial village and Government Station, the names and boundaries of major land units as assigned by the colonists, and major geographic features. The landholdings to which Gallagher referred in his 1941 report cited above were apparently those on Ritiati and Noriti, southeast of the village. As it turned out, however, although the work was “commenced,” it was not carried very far before unforeseen events interceded. (Click on the little map to open a larger version in a new window.)

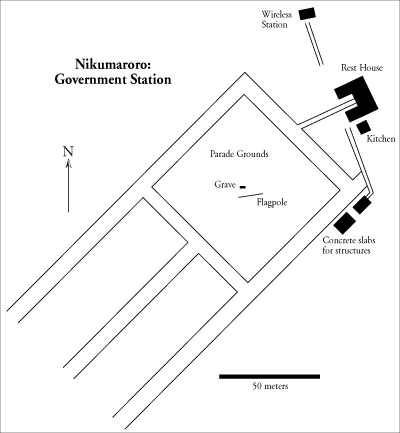

What was carried forward, as indicated in the Progress Reports, was construction of the Government Station and colonial village, later called Karaka after Gallagher. Karaka, or rather the Government Station at Karaka, is now Nikumaroro’s most distinctive archaeological site.

The rendering below is based on contemporary air photos, field observations, and descriptions by Sir Harry Luke in 1941 and administrator Paul Laxton in 1949, and shows the major structures of the Government Station as of now.

The centerpiece of the Station was a parade ground about 65 meters on a side, with a centrally stepped flagstaff. The parade ground was apparently clear of trees and paved with crushed white coral. Seven-meter wide roads ran around three sides of the ground, lined with curbs of small coral slabs; the south side ended in a low, dry-laid coral wall through which passed the road to the boat landing. This road, too, named “Sir Harry Luke Avenue” after the High Commissioner, was also seven meters wide, beautifully leveled, and lined with coral curbs. Facing the parade ground on the east side were two large buildings on concrete platforms – probably administrative structures or perhaps official residences. More ephemeral structures lined the north and west sides, identified by Laxton as including the village carpenter’s home and shop, the boat house, and the school. A substantial concrete-based structure stood near the southwest corner, most likely the dispensary. The wireless station stood on the shore of Tatiman Passage north of the parade ground, where it had line of sight to Ocean Island, the administrative centre of the Gilbert and Ellice Islands Colony. The village itself was south of the Government Center. A typical residential site included a sleeping house and a separate cookhouse, built on the ground or elevated on coral blocks, each building about five meters on a side with pole corners and a thatched roof.

Certainly the most impressive building in the Government Station was the “Rest House,” which served both as Gallagher’s residence and as quarters for visiting dignitaries. Sir Harry Luke describes it as he saw it in late 1941:

... built entirely of native materials, like Holland's and Steenson's at Tarawa, airy, spacious, and far and away the best type of house for Europeans in this part of the world.28

Beyond it the house already showed glimmering lights, and we found our baggage sprawled around ...29

Gallagher himself provides more detail about this house:

This house is considerably more ambitious than that constructed at Sydney Island and, although smaller, is modeled after the Native Lands Commissioner's house on Beru Island .... It is hoped to furnish the main living room of the Rest House with furniture constructed entirely from locally grown "kanawa" – a beautifully marked wood which abounds on the island and is being cut to waste as planting proceeds.30

And Laxton says:

The house had been built by Jack Kima (Petro) in the early days of the settlement. It has a concrete floor throughout, and is perhaps twenty-five by sixty feet, the whole under a tall thatched roof carried on te non and pandanus poles. The centre space is divided into three rooms of approximately equal size by partitions eight feet high made of the centre ribs of coconut leaves, called te ba, leaving a four foot varanda all round. An office stood off the west side on the north end, and a balancing structure on the southern end housed the bathroom, lavatory, and washroom. An American lady who had visited with us earlier when the house had been unoccupied for some time, had proceeded to the lavatory, which is of the 'thunder-box' variety and found it full of dynamite, having been allocated by the island government as an explosive store. This adjusted, she later washed in the neat and impressive handbasin, with tap, plug and all, mentally apologising for reproaching the British with lack of push-pull sanitation; on removing the plug the water gurgled happily away, emerging immediately around her feet. A bucket should stand below to receive the waste. These and similar details had been squared away before our arrival, and the kitchen, too, a corrugated iron roof outhouse, was ready for action.31

Below are photos of the Rest House from 1941 (left) and 1989. The corrugated iron cookhouse remains intact, but the wood and thatch superstructure of the house proper is gone, apparently burned to judge from the charred beams and posts lying on the concrete floor.

|

|

What remains is a U-shaped concrete slab with the charred remains of eleven support posts set in its edges. The south corner lacks a post, being supported by the building’s most remarkable feature – the “thunderbox lavatory” referred to by Laxton. This is a rectangular concrete structure, about two by three meters with walls about 30 cm. thick, containing a claw-footed bathtub and perhaps other facilities, obscured by a fetid mass of decaying coconuts and fronds.

Foua Tofiga of Tuvalu, a friend and colleague of Gallagher’s who visited the island in December of 1941 with Sir Harry Luke, described the working of the “thunderbox” lavatory for us. As Mr. Tofiga explained it, the walls were built strongly to support a tank, into which water was pumped by hand so as to flow by gravity to the taps below.32 The tank has disappeared (though three galvanized iron tanks lie next to the cookhouse), but pipes and parts of a handpump still lean against the southeast wall of the “thunderbox.” The Rest House’s thatch or mat walls must have covered the concrete walls of the lavatory, which are quite invisible in the 1941 photograph.

The Rest House is the only government structure on the square that is not aligned parallel to the peripheral streets. In fact it is on a diagonal, with a short walkway running out to the road. The main entrance to the house was apparently in the inside center of the “U.” Around the northeast and south sides, and probably once extending around the north side, a slab-lined pathway may be the remains of the veranda that Laxton refers to. Beyond this to the northeast is a perfectly rectangular depression, perhaps a formal version of the sunken gardens where I Kiribati grow taro and other root crops referred to as babae. From the house, the view across this landscape feature to the lagoon beyond must have been stunningly beautiful, especially at sunrise and sunset.

Beginning of the End

Thus in early 1941, Gallagher could look out from the Rest House veranda on Nikumaroro, Back.k on two years of high accomplishment, and forward toward a mature and productive new colony. But neither Gallagher nor the PISS were destined to survive. With war raging in Europe, and the Battle of Britain in full swing, Government had little time for far-flung expansions of the Empire, and it became more and more difficult to find the shipping and supplies needed by the fledgling colony. After less than a year on Nikumaroro, Gallagher received a telegram from WPHC Secretary Henry Harrison Vaskess. The telegram advised him that the colonial ship Nimanoa was to sail for the Phoenix Islands about 3rd June, 1941 to convey stores. Vaskess proposed that Gallagher travel aboard Nimanoa to Beru in the southern Gilberts to select and transport the "final batch of settlers."33 The Resident Commissioner of the Gilbert and Ellice Colony recommended against this, citing shipping uncertainties,34 but on 16th June the High Commissioner, Sir Harry Luke, notified ResCom David Wernham that Nimanoa was expected on the 22nd with Gallagher aboard. Wernham replied with a question: was Gallagher coming on to Ocean Island or going to Beru? Sir Harry replied:

Gallagher will remain in Suva and later embark on vessel undertaking distribution of coast-watching personnel and equipment.35

By this time, of course, Britain had been at war with Germany for over a year and a half. Japan had not yet entered the war, but it was expected to, and the Empire was beginning to establish its network of coast-watchers across the islands of the Pacific. Sir Harry had decided that Gallagher was to play a role in this preparation for war; he was

... to explain to natives in each island object of coastwatching, make necessary arrangements with Native Governments and natives and enlist their assistance.

This was only a temporary assignment, however.

He will then take charge of settlers and proceed with them to the Phoenix Islands. He will probably visit Ocean Island in Viti but only for period of stay of vessel there.36

The voyage in Viti, another colonial vessel, would be Gallagher’s last. Ironically, one of the last things he did before sailing was once again to sit for his examination in I Kiribati. This time he passed.37

The Voyage of the Viti

Foua Tofinga, at the time employed in Sir Harry Luke’s office, recalls Gallagher vividly. He describes him as a man of great energy and humility, a man of the people who worked side-by-side with his I Kiribati and Tuvaluan colleagues in whatever endeavor they were assigned to perform. Harry Maude has described Gallagher as “indefatigable”38 and Tofinga’s description is consistent with Maude’s. Tofinga assisted Gallagher in loading Viti with supplies for the coastwatchers. This had to be done quickly and in secrecy, he says, and according to a very strict system. The equipment and supplies were in essence palletized, everything for one island going in one set of marked containers, everything for another going in another. Packing and loading it all was a tremendous logistical challenge considering the time constraints and need for secrecy. Tofinga recalls Gallagher working through the night with him and others to complete the job on time for Viti to load her coastwatchers and set sail. Tofinga did not sail with Gallagher, but Gallagher’s friend and colleague, Dr. Duncan Campbell McEwan (“Jock”) Macpherson, did. This was to prove fortuitous for our understanding of Gallagher, if not for Gallagher himself.

The Viti discharged coastwatchers and their equipment at islands in Tuvalu before sailing on toward the Phoenix Islands and the resumption of Gallagher’s work. There is no evidence that he had been able to pick up any more colonists for Nikumaroro, but he doubtless looked forward at least to getting "home" and continuing the clearing, planting, and assignment of lands.

On 20th September, however, Sir Harry sent Gallagher a coded telegram:

For your personal and secret information ..., there is to be a change ... in the holders of the posts of Resident Commissioner and Secretary to Government at Ocean Island. Garvey is proceeding in John Williams to take over ... and act as Resident Commissioner .... I would like you to accompany Garvey ... in order to act as Secretary to Government. Telegraph your views urgently.39

A step up in the career of a rising young star in the colonial service. But Gallagher did not reply. Sir Harry sent follow-up telegrams, but the response, on 24th September, was from Dr. Macpherson:

Regret inform you Gallagher has been very ill since Saturday 20th. Symptoms which are those of acute gastritis have not abated and are being much aggravated by sea conditions. Patient also suffering from severe nervous exhaustion due to constant strain and worry present assignment in pursuance of which he has not spared himself.... I consider he is quite unfit to undertake strenuous secretarial duties and present and should remain quietly Gardner Island where his presence is also much needed...40

Death on Nikumaroro

Sir Harry promptly suggested that Gallagher return to Suva for treatment, but by this time Viti had arrived at Nikumaroro. On 26th September Macpherson reported that Gallagher had been ashore 40 hours, but was very weak and suffering from "mental prostration."41 Then came a telegram from Viti's Captain:

Regret inform you Gallagher very low. Macpherson operating now.42

And then from Macpherson:

Gallagher suddenly became much worse about noon today and symptoms of acute obstruction became apparent. Operation imperative and with his full consent I explored abdomen this afternoon. Early signs peritonitis apparent. Obstruction due to old adhesions.... Fear gas gangrene. Prognosis very grave indeed and I recommend you inform parents accordingly.43

And then –

Deeply regret inform you that Gallagher died 1206 a.m. 27th. Awaiting any instructions.44

A series of telegrams followed in which Sir Harry notified the Secretary of State in London and Gallagher’s colleagues, expressing his grief at the loss of one of the Colony’s “most devoted and zealous officers who never spared himself in bringing the Phoenix Islands Settlement Scheme to successful conclusion.”45 Macpherson remained on Nikumaroro until the 28th, arranging for Gallagher’s burial and the disposal of his effects and generating a good deal of correspondence in the process. All concerned, including the crew of Viti, sent their condolences to Gerald’s parents, and there was a bit of a flap when Wernham transmitted these expressions outside channels.

Post-Mortem

A separate, thick file in the WPHC archives at Hanslope Park is given over to documents generated about Gallagher after his death. Macpherson provided a detailed accounting of how he had handled Gallagher’s effects on Nikumaroro – shipping most on Viti but honoring Gallagher’s wish that his Tuvaluan canoe and various household goods be given to Aram Tamia.46 Harry Maude wrote Sir Harry on behalf of himself and Honor:

We were both terribly upset to hear the news about Gallagher – what a blow it is to the Gilbert and Ellice, as he was by far the best man we had. It was some time before we could realize that he was no more. He was the only officer of the pioneering type in the Colony and now that he has gone it is difficult to see who can ultimately take over ...47

The eulogy spoken by Lt. Commander Mullins at graveside on 27th September is preserved in the file, ending with:

He lies buried where he would wish to be – near the flag which he served unto death – on the island, the settlement of which he was the founder – among the people he loved and for whose welfare he worked without ceasing. God grant him peace.48

Correspondence between Sir Harry and Harry Maude document their agreement that Maude would collect money for a memorial plaque on Niku.49 A letter from Sir Harry to Gerald’s mother, Edith Gallagher, expresses his sympathy and grief.50 Mrs. Gallagher’s gracious response is in the grand tradition of the British stiff upper lip.51 Fate and the War were hard on Mrs. Gallagher; in another letter to Sir Harry several months after the first, she mentions that:

I have had another great sorrow– my younger son Terrence was killed in Malta during the very heavy air-raid there on Saturday March 21st.... Life’s road will seem very long and drear without the companionship of these two beloved sons, but they were both gallant lads and I must try to carry on bravely – they would not wish it otherwise. But oh, the loneliness and sadness of it all!

She concludes:

My heart lies buried in two islands now – Gardner and Malta. God grant that the war will soon be over with all its suffering and tragedy.52

Terrence’s death was not only a sorrow for Mrs. Gallagher; it complicated things for the WPHC, because Gerald had named Terrence the executor of his will.53 This was eventually worked out through the good offices of Harry Maude. Gerald’s effects turned out to be remarkably substantial – forty tennis shirts with collars, three sports coats, several full suits, a tennis racquet, a well-equipped toolchest, a flyer’s helmet and goggles, photographs and negatives, two wireless sets, two canoes, a fishing rod, a Colt .22 automatic, four brass ashtrays, two butter pats. All this was meticulously recorded in two partly overlapping inventories.54

Macpherson’s Story

Perhaps the most remarkable, and eloquent, document in the WPHC file is a thirteen page memorandum to Vaskess from MacPherson, detailing the events surrounding Gallagher's demise. It is far too long to reproduce here in full, but a few excerpts will, perhaps, capture its flavor.

He was ... suffering from a certain degree of physical and mental exhaustion owing to his complete absorption in the innumerable preliminary arrangements necessary for carrying out so complicated a programme as that marked out for the vessel. Upon arrival at Niulakita, a boat from H.M.F.S. Viti made an attempt to land. Mr. Gallagher and myself were both members of the landing party, and when it was obvious that no landing was possible through the tremendous surf prevailing, Mr. Gallagher prepared to swim through the breakers in order to ascertain the extent to which repairs were required to the existing buildings on the island. He was only dissuaded from this purpose with the greatest difficulty.

At every stage of the voyage Mr. Gallagher worked unceasingly – often far into the night – and on occasions, when cargo was being loaded, all night .... When ... unavoidable delays occurred Mr. Gallagher gradually became obsessed with the necessity for speeding up the vessel's schedule, and finally the saving of even a few hours time became with him a primary objective.

Despite all attempts to induce him to remain ashore (on Tarawa) until convalescence was more advanced, he returned to his duties at the earliest possible moment. He was given a tonic mixture and made some progress, although his appearance was gaunt and it was obvious that he was suffering from nervous exhaustion.

The completion of the tour and his final settlement at Gardner Island now became a complete obsession with him. He spoke of this constantly, and apparently he looked forward to a quiet period which would enable him to read the large quantity of mail which had accumulated for him at Ocean Island, and to take up the threads of his work in the Phoenix Is.

On arrival at Gardner Island the weather conditions were far from favourable, and he naturally worried a great deal about the landing of the stores and other material for which he had waited so long. The unavoidable loss of some of these stores, particularly reinforcing iron and timber, was consequently a severe disappointment. He worked incessantly during this time, sparing only an hour in which to conduct me round the Station in order that we might choose finally the site of the proposed hospital.

After travelling on through the Phoenix Islands, during which time Gallagher's condition worsened, and arriving at Canton Island...

He ... assured me that he felt he would only recover in his own house on Gardner Island and amidst his own native people.

After leaving Canton Island, your telegram (unnumbered) of 30th [?] September was decoded by Mr. Hogan, and its contents were communicated to Mr. Gallagher [Note:the "3" in "30" has been struck through and replaced with another number, but it is not clear on our photocopy what the number is. Given the chronology of events, this was almost certainly the telegram of 20th September in which Sir Harry asked Gallagher to go to Ocean Island as Secretary to Government]. Its effect on him in his then agitated mental and weak physical state was profound. He told me that he felt that he was "at the end of his tether," and that he proposed to go ashore at Gardner Island and remain there until he was well.

At Nikumaroro ...

He was carried on a mattress to his own house, which is at a considerable distance from the landing place. He was more cheerful that evening and passed a more tranquil night than any since the commencement of his illness. Physical signs were still absent. He proved an extremely difficult patient to manage, insisting on trying all kinds of foods for which he had a passing fancy, and refusing to be washed or otherwise nursed in any way.

There follows a detailed account of Gallagher’s precipitous decline, Macpherson’s operation, the shocking condition of Gallagher’s intestinal walls (“no thicker than tissue paper, and highly suggestive of the disease, resulting from malnutrition, and known as sprue”), and Macpherson’s valiant but unsuccessful efforts to stabilize his condition. Finally:

I informed the Native Magistrate and others that the end was near. They assembled round his bed, and those who profess Roman Catholicism, led by Mr. Hogan, sat by his bed and offered him the spiritual consolation which the rites of the Roman Catholic Church provide for the dying. His passing at 12.7 a.m. on the 27th September was completely peaceful.

At dawn, with the assistance of Mr. Whysall, I pegged out an area at the base of the flagstaff in an east and west direction and a grave was prepared, and lined with coconut fronds .... The coffin was draped with a new Union Jack and was carried on the shoulders of representative numbers of Europeans, Fijians, Ellice Islanders and Gilbertese. At the gravesite Lieut-Commander Mullins read the burial service of the Roman Catholic Church and the hymn Nearer My God to Thee was sung by the Europeans present. Lieut-Commander Mullins spoke a few simple and appropriate words (a copy of which have already been given to His Excellency). The Protestant natives sang a hymn in Ellice, and subsequently Maheo, an Ellice Islander, and one of the native wireless operators, paid a simple, eloquent, and most touching tribute (in English) to Mr. Gallagher's memory. After the grave had been filled in, the native women on the station placed garlands of bush flowers around it.

The whole setting of this sad scene was impressive, and to any onlooker would have presented a striking picture. A dense mass of green bush in the Back.kground, the glistening white sand of the Government Station with its careful planning and its wide avenues fringed with young coconut palms, the bright cloudless sky, the infinite variety and graduations of colour in the lagoon in the foreground, the myriads of seabirds whirling overhead, the group of Europeans wearing Service uniform and natives clad in spotless Sunday garb – all assembled and bareheaded beneath the flagstaff where the flag was flying at half-mast.

I had decided long prior to Mr. Gallagher's illness ... to write semi-officially to His Excellency the High Commissioner and express my personal admiration of the excellent work which this young officer had accomplished .... The vision and judgement which he showed in the laying out of the new settlement will be apparent to all who may have occasion to visit the Phoenix Islands in future, and will remain, I trust, as an enduring monument to a faithful and able officer, and a very gallant gentleman.

Before he left Nikumaroro, Macpherson was given a letter by Gallagher’s servant, Aram Tamia, with the request that it be posted to Gerald's mother:

I have lost the most wonderful, kind, good and thoughtful master that any servant ever had ....

Mister Gallagher is laid to rest at the foot of the flag-mast, and the flag he taught us to love and respect waves over him every day.

We, the people who dearly love him, are going to tend his resting place. It is also for that reason, and a custom of my people, that I am remaining here for some time with my master.

Please will you, his mother, accept from me, his sorrowing servant, my deepest sympathy in your sad loss of such a good son and man.

Your obedient servant,

Aram Tamia55

Karaka Village and the Uen Maungan I Karaka

A little over a month after Gallagher’s death, the World War came to the Pacific, and Kiribati was invaded. The Japanese did not attack the Phoenix Islands, however, and allied air bases were established on Kanton. Although some residents of Orona, Manra and Nikumaroro went to Kanton to work, and although a U.S. Coast Guard Loran station operated on Nikumaroro from 1944 until 1946, the colonists were essentially isolated from the world, visited only occasionally by colonial officers from Kanton. Left to themselves, they subsisted on traditional foods and what they could glean through occasional wage labor on Kanton and by selling handcrafts to the Americans.

Gallagher had only begun to demark and allocate land to colonial families, so the bulk of the land and its seedling coconut trees were still regarded as comprising a government plantation. Without central direction, and with the market for copra uncertain at best, the islanders seem to have devoted rather little time to the trees, and the plantation fell into disrepair.

Not so the Government Station and the abutting village, however. Renamed Karaka after Gallagher, the village and Gallagher’s grave were very well maintained. Gallagher’s erstwhile servant, Aram Tamia, evolved into the island magistrate, and kept his promise to Gallagher’s mother. In 1944 a visiting colonial officer reported that “the village area was clean and doing well,” though “elsewhere secondary bush was encroaching.”56

After the War, a new official of the Gilbert and Ellice Islands Colony, Paul Laxton, spent time on the island, and wrote an important account of it. It appears that while the colonial village – now named “Karaka” in Gallagher’s memory – had survived the War, and been lovingly maintained by its residents, it had stagnated economically. In other words, it was not producing copra. Part of the problem was that by the time of his death, Gallagher had not yet finished dividing up the land and assigning parcels to permanent colonists. The colonists, one reads between the lines of Laxton's article, didn’t see themselves as landowners but as government employees, responsible for maintaining the village’s assets while eking out a subsistence living, but with little investment in the coconut plantations. Laxton's mission was to change all that.

[I] flatly presented this hard, realistic, Gideon-like policy. The weaker members should pack up and go: if they proved to be a great proportion of the island community then the whole settlement would be given up and a copra plantation formed. Otherwise, new blood would come in on a system of leaseholds, receiving a block of planted land in return for which they should clear and plant specified areas for government. After three years the future of the pioneer settlement would be reviewed. This brusque challenge is what Nikumaroro needed....57

The colonists responded positively to Laxton’s pitch, and in short order the coconut land of the island was divided into plots and assigned to families. More colonists came in from Manra, and the village itself was relocated. One gets the impression that Laxton was intent on getting the residents away from the Government Center that Gallagher had overseen, with his grave and all the other reminders of the time before the War, and focus their attention on cultivating coconuts. Apparently this worked; the Gallagher-era village was effectively abandoned, and the colony’s center of gravity shifted south along the southwest side of the island.

But Gallagher was not forgotten. Laxton reported that:

Recently the islanders built and dedicated their permanent maneaba, that combination of assembly hall and shrine of tradition which is the centre of Gilbertese community, and named it "Uen Maungan I Karaka," an idiomatic phrase which may be equally translated "Flower to the Memory of Gallagher" and "The Flowering of Gallagher's Achievement." Thus they commemorate the English gentleman whose devotion and leadership made their new home possible.58

In 1989, surveying along the lagoon shore of the village, we found the remains of what must have been Uen Maungan I Karaka. The maneaba, eighteen meters long and ten meters wide, sat on a low coral rubble platform lined with coral slabs. The structure itself had completely collapsed, but for two standing posts. It had apparently had a peaked roof that collapsed to the northwest, and a number of curving roof members. The most interesting feature of the maneaba, besides its size and unique curved roof members, was the fact that it was painted. The standing posts were painted in alternating bands of red, blue, and white, and at least some of the roof members were blue with white stars and spots. The “Flower to the Memory of Gallagher,” in other words, was painted in the colors of the Union Jack.

In the end, Laxton’s “Gideon-like” policy failed to bring about the economic renaissance he hoped for, particularly in the face of a series of drought years that followed its imposition. Based on the testimony of his consultants, former residents of Manra, Knudson describes the decline of the colony there, whose fate would be shared by those on Orona and Nikumaroro a few years later.

It appears that this lengthy [drought] crisis prompted the [council of elders] of Sydney Island to request the government to move them elsewhere. The request was not a unanimous one. There was considerable discussion of the matter, with some of the elders agreeing and some disagreeing. The young men appear not to have been in favor of moving. Those I talked to in the Solomons said they enjoyed the dry climate and felt that there was always sufficient food.

As the drought continued the elders gradually came to agree among themselves that the island was not permanently habitable. Finally in the early 1950s they sent a deputation to Tarawa. Convinced that Sydney Island had been the hardest hit by the droughts, and that there was little chance that conditions there could be much improved, the officers of the central administration determined to move the islanders elsewhere.59

By the early 1960s Nikumaroro, Orona, and Manra were all abandoned. It is almost as if the colony failed for want of nerve, and one has to wonder how much the loss of its pioneer leader and advocate had to do with this. Residents of Nikumaroro Village in the Solomon Islands, whence many of the colonists from its namesake island were moved, still evince puzzlement over why they had to leave, and the Kiribati government periodically studies reviving the PISS. Nevertheless the die was cast and in 1963 the last Nikumaroro settlers steamed away, leaving the island to the birds and coconut crabs that populate it today.

They left what seems to have been a fairly healthy coconut plantation, now a dense, feral jungle, and the rapidly decaying ruins of their homes, their maneaba, and the Government Station. And at the centre of the latter, the last monument to the colony’s hero.

In the middle of the parade ground is Gallagher’s grave, lovingly constructed by the natives to MacPherson’s design.60

Designed by Dr. Macpherson, Gallagher’s grave monument resembles that of Robert Louis Stevenson in Samoa.61A house-shaped structure of concrete, probably over a coral core, it sits on a low rectangular platform lined with small slabs.

The files of the Western Pacific High Commission indicate that shortly after its construction a bronze plaque was affixed to its end, paid for with subscriptions collected by Harry Maude, that read:

In

affectionate Memory

Of

GERALD BERNARD GALLAGHER, M.A.

Of the Colonial Administrative Service.

Officer in charge of the Phoenix Islands Settlement Scheme

Who died on Gardner Island, where he would have wished to die, on the

27th September, 1941, aged 29 years

.....

His selfless devotion to duty and unsparing work on behalf of

The natives of the Gilbert and Ellice Islands

Were an inspiration to all who knew him, and to his labours is largely

Due the successful colonization of the

PHOENIX ISLANDS.

R.I.P

:::::::::::::

Erected by his friends and brother officers.

This plaque has disappeared*, but TIGHAR replaced it with a similar plaque in 2001. At the east (head) end of the grave, in traditional I Kiribati fashion, the colonists planted a young coconut tree. By 1989 when we first saw the grave the tree was quite large, and a coconut crab (Birgus latro) had made its home at its foot, burrowing under the grave structure. The crab was caught and eaten by our Fijian ship’s crew.

* We have subsequently learned that on the abandonment of the village, Gallagher’s remains and the bronze plaque were retrieved at his mother’s request, and he was re-interred on Tarawa, where he still rests.