|

by

Gary Quigg & Thomas F. King, Ph.D.

The International Group for Historic Aircraft Recovery

November 2007

Documenting the site of an historic, or at least old, aircraft wreck can present daunting challenges. Such sites – or at least those that have survived in recordable condition – are usually in more or less remote areas, and often in rugged terrain. People who are interested enough in such wrecks to seek them out and try to record them are often volunteers, with limited time and money to spend on the enterprise.

In the course of several crash-site documentation projects, The International Group for Historic Aircraft Recovery (TIGHAR) has developed a relatively simple, fast, and inexpensive method of mapping a wreck site. This brief paper describes the method, using several TIGHAR projects as examples.

|

| Wreckage at the Idaho site. |

One of TIGHAR’s long-term research projects is a study on Nikumaroro Island in the Republic of Kiribati, where we hypothesize that pioneer aviators Amelia Earhart and Fred Noonan landed and expired after their disappearance in July of 1937.1 In 2004, seeking comparative data on aircraft contemporary with and as similar as possible to Earhart’s Lockheed Electra 10E, we located and inspected the site of a 1936 crash on the St. Joe National Forest, not far from Kellogg, Idaho. The aircraft was a Lockheed Electra 10A #1024, registered as NC 14935. A Bureau of Air Commerce analysis of the crash concluded that Pilot Joe Livermore and co-pilot Arthur Haid had become lost, and perhaps had trouble with their instruments, though local media accounts alluded to bad weather conditions as well. Livermore and Haid were killed in the crash into a mountain ridge, where their bodies, together with several sacks of mail, were recovered a week later.2

TIGHAR’s seven-person team of volunteers traveled to the site with representatives of the U.S.D.A. Forest Service and the Coeur d’Alene Tribe on July 9, 2004. Four-wheel drive vehicles got us within a two-hour hike of the ridge on which background research indicated the plane had crashed. We arrived on the ridge in mid-afternoon and quickly set up camp, then deployed across the ridge slope to perform an informal transect survey, which quite quickly revealed the crash site. We undertook the site’s documentation on July 10.

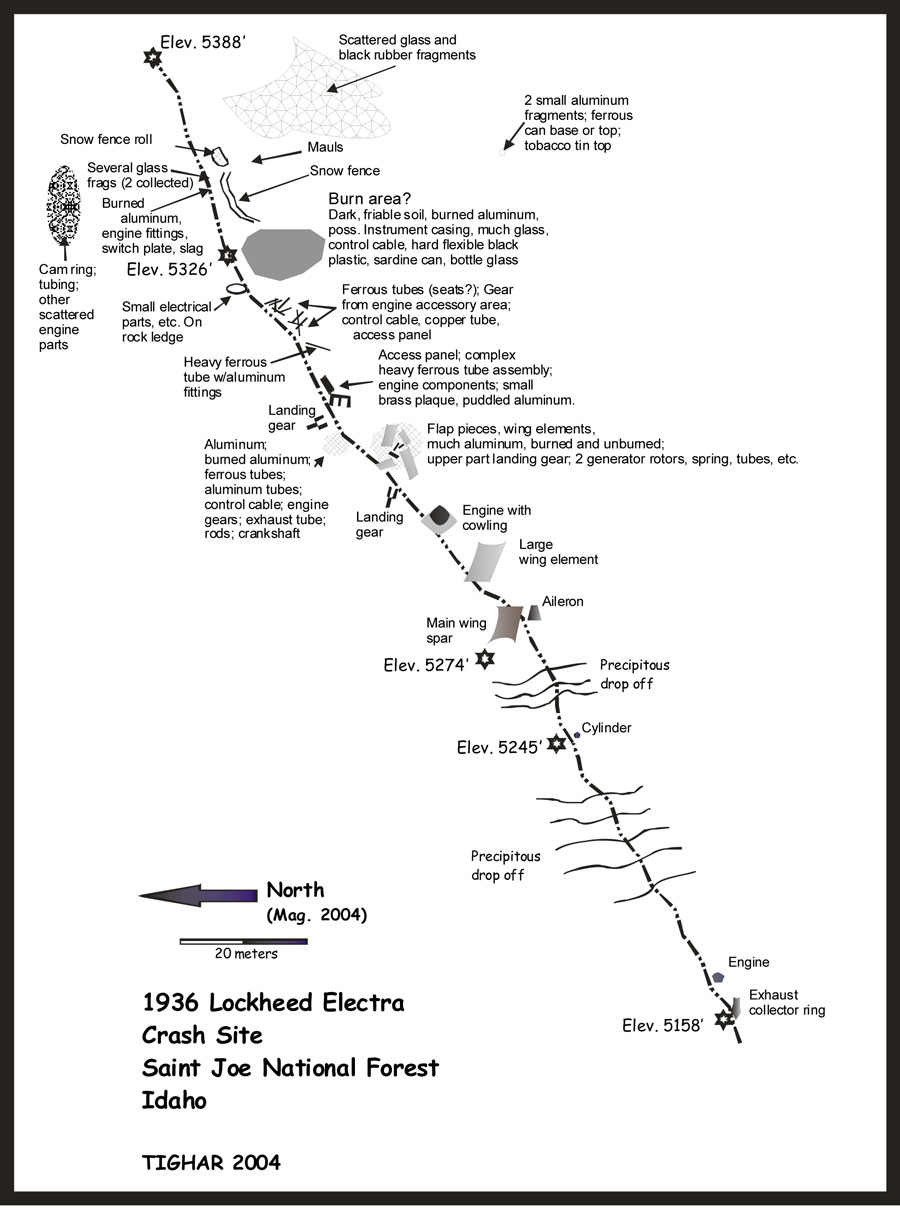

The plane had struck the ridge about 100 meters below its crest; the point of impact was marked by scattered glass fragments, burned aluminum, rubber pieces, and other debris. Most of the wreckage, however, had slid down into a gully that bisects the site from northeast to southwest. The fuselage had apparently been recovered, probably for scrap during World War II.

The wreckage is distributed for about 150 linear meters (500′) along the steeply pitched, steep-sided ravine of a snowmelt-fed stream (dry at the time of our survey) that runs west-southwest, joining a larger creek about half a mile below the wreckage concentration. Very little wreckage is apparent on the slopes above the streambed; what was found there comprised small fragments of glass, aluminum, and hard rubber. The streambed runs through a landscape of metamorphic rubble, over a series of sharp rock outcrops that must form waterfalls when the stream is flowing. There is a fair amount of riparian vegetation along the streambed itself, increasing dramatically downstream toward the mainstem of the creek into which the stream empties. The headwaters are sparsely vegetated for 20 to 40 meters (35–70′) in all directions from the streambed, surrounded by lodgepole pine forest with knee-to-waist high wild huckleberry and other brush.

To document the site, we were equipped with a sixty-meter tape measure, several three and five-meter tapes, compasses, Global Positioning System (GPS) units, digital cameras, and basic recording tools. Our challenge was to prepare a quick but useable base map of the site on which to plot significant wreckage concentrations, particularly important elements of the aircraft, and the locations where we took record photographs.

While three team members searched downstream (without success) for more wreckage, the rest of us began recording by establishing a control point (datum point) just beyond the upstream end of the apparent wreckage distribution. We documented this point’s location and elevation using GPS. Securing the sixty-meter tape to this point, we ran the tape down the gully as far as it would go on a direct compass heading. Meanwhile, two team members scoured the ravine and its banks, marking wreckage with pin-flags. It was a relatively easy matter to measure in each major piece or concentration of wreckage with reference to the initial baseline represented by the sixty-meter tape, by simply measuring along the tape and outward from it using the shorter tapes and compasses. We then brought the end of the long tape down to the end of the first segment, again took a compass heading and stretched the tape out as far as possible, recording everything along its route as before. We continued this procedure down to the point at which the wreckage petered out, thus producing the map shown in Figure One.

Figure 1: Site Map of Idaho Crash Site

| 1 | See King et al 2004; Gillespie 2006. For a précis of TIGHAR’s Nikumaroro Hypothesis, see Amelia Earhart’s Fate: The Archaeological Investigations. |

| 2 | For details see TIGHAR 2004. |

| Introduction & The Kellogg Site | Refining the Method: Misty Fjords & Colonia Airport | Maid of Harlech & Conclusion | Bibliography |

|

Copyright 2023 by TIGHAR, a non-profit foundation. No portion of the TIGHAR Website may be reproduced by xerographic, photographic, digital or any other means for any purpose. No portion of the TIGHAR Website may be stored in a retrieval system, copied, transmitted or transferred in any form or by any means, whether electronic, mechanical, digital, photographic, magnetic or otherwise, for any purpose without the express, written permission of TIGHAR. All rights reserved. Contact us at: info@tighar.org • Phone: 610.467.1937 • JOIN NOW |